Brexit debate unnerves continent’s service workers in UK

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Hernan Lazo Mina is part of a hidden army of workers who make places like London run. Between dusk and dawn they fan out into the city’s empty offices to clean the toilets, sweep the floors and empty the bins. Many of them are migrants like Mr Lazo Mina, who came to the UK from Spain, where the unemployment rate is still above 20 per cent. Now he is worried the British people want him gone. “They might think that leaving the EU, that would get rid of us, they wouldn’t have to see us here,” he says.

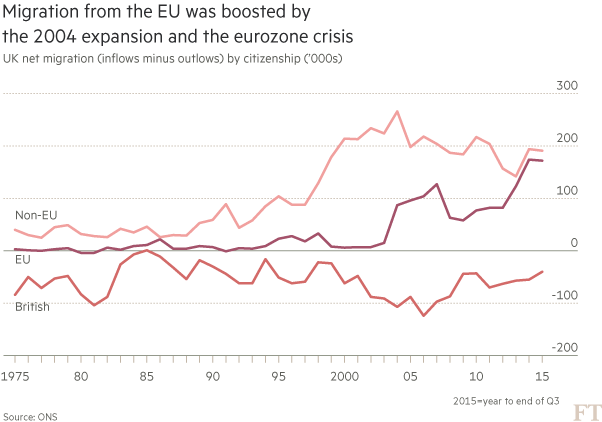

Immigration is at the heart of the UK’s June 23 referendum on whether to leave the EU. The number of EU nationals working in Britain has doubled since 2007 to about 2m as people such as Mr Lazo Mina have flocked to one of Europe’s more robust economies.

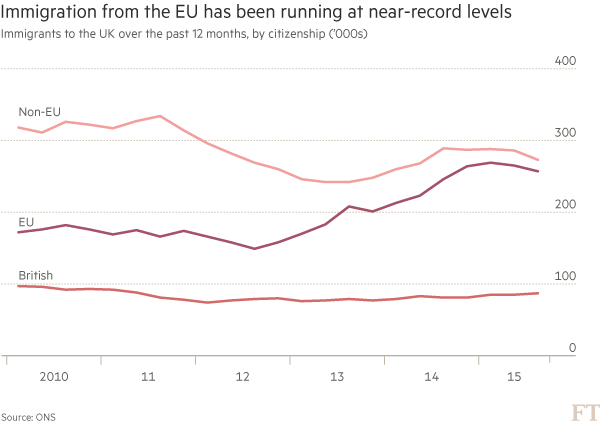

The Conservative government has tried and failed to reduce immigration: fewer people are now arriving from outside the EU but those coming from within are running close to record levels — last year 257,000 EU nationals moved to the UK for at least 12 months. National insurance registrations suggest the numbers applying to work in the country in 2015, including for short-term stints, may be at least twice as high.

Many of those campaigning for Brexit say that only by leaving the EU can the UK take control of its borders and stem the flow of migrants, who they say are overwhelming public services and undercutting UK-born workers.

The debate has already unnerved some of the EU citizens who live and work in the country — particularly those whose lives are already characterised by insecurity.

The mood is far calmer in the affluent French community in Kentish Town in North London, where mothers and nannies gather outside the gates of the local bilingual primary school and teenagers slope home from the secondary school up the road, chattering to each other in French.

In the London coffee shop where Maritza Castillo Calle works the conversation has turned anxiously to what would happen to them if the British people chose to leave the EU. “We were all talking about it the other day, saying what’s going to happen?” the 30-year old says. “Some of them have lots of people in their family that came with them, and to all go back? How are they going to do that?”

“When I walk down the street I hear nothing but French, I’m appalled! You don’t feel like you’re special any more!” says Cynthia, who moved to the UK from France three years ago for her banker husband’s job.

She thinks the French community is good for London’s economy — more than 6,000 French nationals work in the City of London financial centre — and is confident they would not have to leave in the event of Brexit. The other French mothers, she says, do not seem to talk about it at all.

Lucie Regent, who has lived in the UK for 15 years, says it would be “the beginning of the end for the EU” if the UK voted to leave, but does not foresee any personal repercussions. In any case, she thinks the British will vote for the status quo in the end. “It’s like Scotland, they just like the drama,” she says, referring to the 2014 referendum that eventually rejected Scottish independence. “I never thought the English would be so dramatic!”

Steve Peers, a professor at Essex University who specialises in EU law, argues EU migrants already in the country have little to fear. “Anyone who’s here on Brexit day gets to stay here legally; that would be the gist of it,” he says.

But any impact on new migrants is much harder to predict.

Prof Peers says the UK could try to negotiate a deal that allows free movement for some groups but the right to impose quotas on some others. There is no guarantee the EU would agree. No country has been given full access to the bloc’s single market without accepting free movement. In the most extreme scenario, the UK could revert to fully national borders.

Ms Castillo Calle does not understand why some people say they want to stop workers like her from coming to the UK because they are undercutting British people’s wages. In fact, she says, they are fighting for higher wages and better conditions. She chairs a branch of the Independent Workers’ Union of Great Britain, which has negotiated higher wages for cleaners in several workplaces including her own.

Mr Lazo Mina thinks the economy would suffer if the UK clamped down on migration because not many British people would want to do what he does. He cleans one office between 7pm and 10pm, then moves to another where he works from midnight to 8am. He arrives home at 9am, sleeps for six hours, and starts again.

“If the UK decides to leave EU and, all of a sudden, there’s no one to do the work of cleaning offices and cleaning the toilets, the British people will have to do that work, or the CEO will have to clean his own office,” he says, “Then they’ll understand that we are important.”

1. Low unemployment makes the UK attractive

The latest official statistics show that only Germany and the Czech Republic have lower unemployment rates than the 5.1 per cent UK rate, highlighting the ease of finding work in Britain. With the employment rate for those aged 16 to 64 also at a record, Britain’s labour market shows no signs of struggling to employ people.

2. Relatively high wages on offer

Although comparisons depend on the exchange rate and sterling has recently weakened sharply, the UK minimum wage for a full-time employee was the third highest in the EU in January and is set to rise into second place for those over 25 after the higher minimum wage of £7.20 an hour is introduced in April.

3. EU migration both high and low skilled

Migrants from western Europe have a significantly greater proportion of university graduates. Those from eastern Europe are harder to quantify as many have qualifications that do not translate easily into the UK system, but are more likely to be vocational and lower skilled.

4. EU migrants have little measurable effect on wages

Studies have concluded that areas of high EU migration do not suffer a serious wage penalty compared with those of low migration. Any depression in wages from EU migration appears to be small, although migration probably acts as a safety valve for employers, allowing them to recruit more labour at prevailing wage rates when business is strong.

5. Britain has attracted many migrants in recent years

Net migration from the EU has risen sharply over recent years to 257,000 in the year to September 2015. The rise reflects the strong economic situation of the UK relative to other EU countries and high relative wages. But Britain is not alone in hosting about one in eight people who were born abroad. This is in the middle of the European pack, almost identical to Spain and Germany.

Comments