Mass ‘fish kill’ in Australia sparks fight over water management

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

William “Badger” Bates picked up a dead fish and tossed it into a pool of toxic, green water, surveying the destruction of a river that for tens of thousands of years has provided sustenance to the Barkindji people.

“This is the worst fish kill I’ve seen,” said the 71-year-old indigenous elder, who is witnessing an unfolding ecological disaster along the banks of Australia’s Darling River.

“You take this river from me and my people [and] we’re not even black any more. We’ve got no culture, we’ve got nothing.”

Scientists estimate up to 1m fish died last week as a result of a rapid increase in the production of algae, sucking oxygen out of the river.

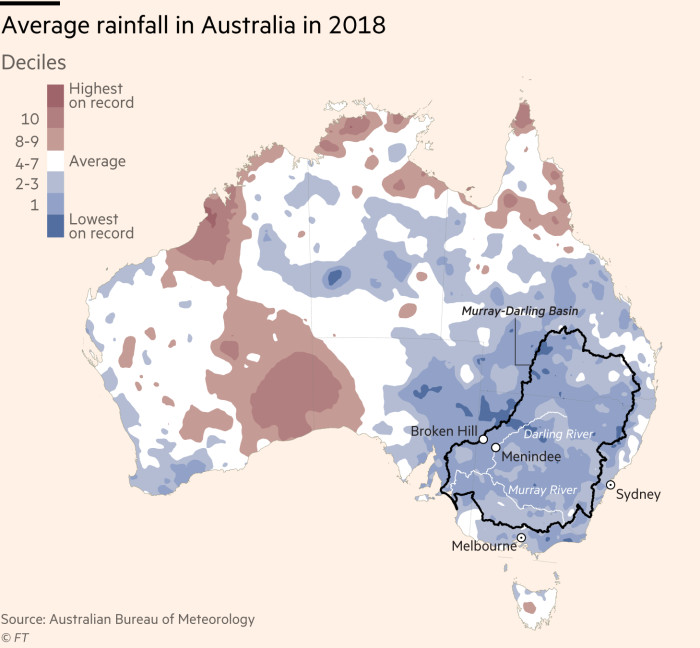

Along with the Murray River, the Darling flows through a fertile region that is the size of Germany and France, and supplies a third of Australia’s food, worth A$24bn ($17bn) a year. Further fish die-offs are predicted and the issue has become a lightning rod in a bitter dispute over water management in a country scorched by drought and where the Liberal-National coalition government is accused of promoting industry over environmental protection.

Conservationists and farmers at the lower end of these waterways blame massive cotton farms in the upper basin for extracting too much water from the Darling and Murray Rivers, which snake across four states towards the Southern Ocean. They say excessive irrigation, combined with low rainfall in one of the worst droughts in a century, is causing waterways to dry up and causing blooms of toxic blue-green algae, which typically occur in slow moving or still water.

The fish die-off has focused attention on a A$13bn ($9bn) government plan launched in 2012 that aimed to restore the health of the Murray-Darling basin. Initially touted as a model for other countries seeking to balance farming and conservation in an era of global warming, some scientists warn political backsliding on the plan’s targets and weak enforcement mean it has instead become a recipe for environmental catastrophe.

“We predicted this fish kill would happen because the plan allows too much water to be extracted by irrigators,” said Quentin Grafton, professor at Australian National University. “It is a nonsense to suggest the current basin plan will work.”

Overall average inflows into basin waterways are 32,500 gigalitres a year, about 65 times the amount of water in Sydney harbour. Some 40 per cent of this water is taken out for use by irrigators, industry and communities for drinking water while evaporation accounts for much of the rest. Only 4 per cent of Murray River water reaches the ocean, highlighting the scale of the challenge.

The 2012 plan initially proposed reducing the amount of water taken by irrigators by 2,750 gigalitres a year, but amendments sought by irrigators — and sanctioned by MPs last year — removed 70 gigalitres of these savings. This is less than the 4,000-4,500 gigalitres minimum level of savings recommended by David Bell, a former director of environmental water planning at the Murray-Darling Basin Authority, according to evidence to an inquiry ordered by the South Australian state government.

This inquiry was sparked by an investigation by Australia’s state broadcaster, which detailed widespread allegations of water being diverted by irrigators and mismanagement by Australian authorities.

“This fish kill has nothing to do with the drought. It’s a man-made disaster caused by government mismanagement,” said Robert McBride, a farmer who discovered the dead fish near the small town of Menindee in New South Wales.

His Facebook video, which showed dozens of dead Murray cod, went viral, forcing federal and state authorities to call emergency meetings and pledge A$5m to a fish rescue plan.

“Many of these cod can live for 50 years and have survived previous droughts,” said Mr McBride.

With a national election due in May, the stakes are high for the coalition which is trailing in opinion polls and faces criticism in towns such as Menindee and Broken Hill, where drinking water supplies are under threat. The government rejects claims of mismanagement and blames record high temperatures and drought.

“I’m always concerned by these Salem witch-hunts that turn dramatic footage, in this case of a fish kill, and try to solve it by burning at the stake a whole section of the agricultural industry,” said Barnaby Joyce, the government drought envoy and former minister in charge of water.

Mr Joyce criticised claims by conservationists that Australia’s A$2.3bn-a-year cotton industry — and specifically the Chinese-owned Cubbie Station, the largest irrigated property in the southern hemisphere at 96,000 hectares — is the “Great Satan” causing waterways to deteriorate.

Cubbie, which is 80 per cent owned by Shandong Ruyi, has a water licence that enables it to extract 460 gigalitres of water a year, almost as much in volume as Sydney harbour. But Mr Joyce said in an opinion article that it grew just 900 hectares of cotton in 2018 and the last time it took water from the river was in 2017.

Cubbie did not respond to a request for comment.

Cotton Australia, which represents growers, said it was wrong to blame its industry for the environmental disaster, which follows a “long and devastating” drought that has forced cotton growers to halve the area under cultivation in the northern Darling basin and stop diverting water.

But as fish die and waterways dry up, the communities living downstream are not convinced.

“Why don’t we look at what is killing this country and cotton is one of those things,” says Mr Bates. “It [the river] could die. It will die.”

Comments