Britain and the cuts: Blow for Cameron as UK faces deeper cuts

Simply sign up to the Global Economy myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

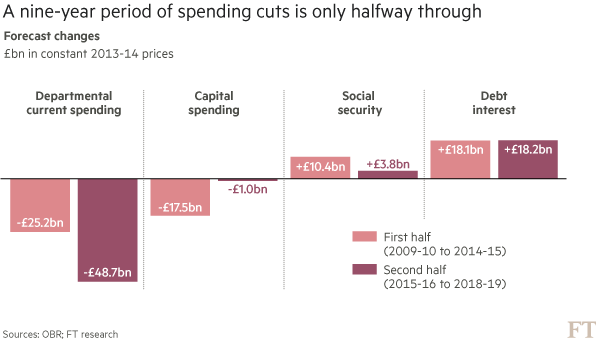

George Osborne must cut deeper into the budgets of the army, police and courts as the annual savings needed to meet his austerity targets are set almost to double to £48bn, Financial Times analysis shows.

As Britain hits the midway mark of its decade of planned austerity, the findings suggest that far from the cuts becoming lighter after 2015 – as the chancellor and prime minister David Cameron have suggested – they are poised to become much harsher for departments outside the protected areas of health, schools and overseas aid.

FT series

Britain is exactly at the halfway point of a planned nine-year programme of cuts, and the second half promises to be more difficult than the first, whichever party wins the next general election.

Further reading

The findings will come as a blow to the Conservative party which, only six months away from a general election, is seeking to attract voters with talk of more tax cuts.

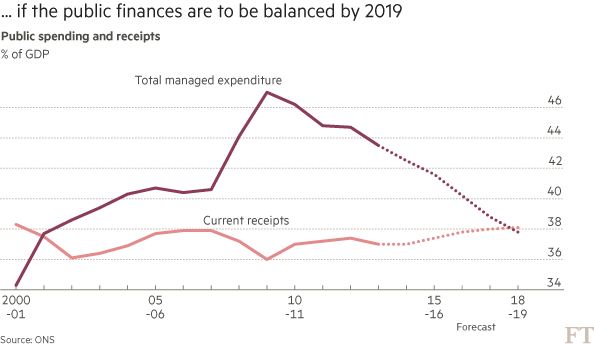

Many experts, including the International Monetary Fund, say taxes will have to rise in the next parliament or more money will have to be borrowed to prevent a serious hit on many public services.

Mr Cameron wrote last month that most of the cuts in the austerity programme had been achieved, with only £25bn a year still to be removed from budgets.

But the FT’s analysis has found that less than half the reductions have been made. The analysis is based on the Office for Budget Responsibility’s Budget figures from March, which outline the government’s spending plans until 2018-19.

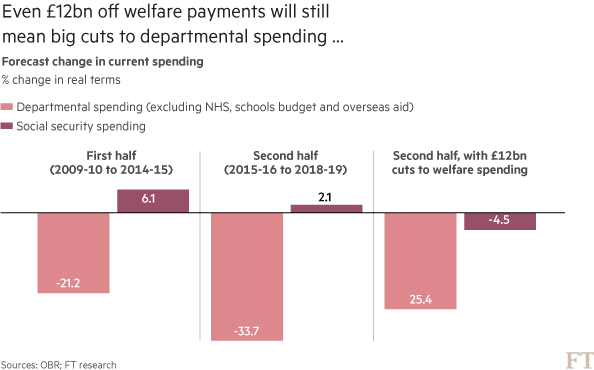

If the next government continues to ringfence health, schools and overseas aid, the non-protected departments face real cuts of 33 per cent, compared with the 21 per cent cuts they faced between 2009-10 and 2014-15.

The FT examined the plans for government departments’ current expenditure after adjusting for expected inflation between 2014-15 and 2018-19 – the second half of this government’s package of cuts to eliminate its borrowings.

The level of cuts are nearly twice the £25bn estimate because that figure does not include planned cuts for two years out of the nine – 2015-16 and 2018-19 – and takes no account of the effect on departmental spending of rising numbers of pensioners and increases in pension payments. The Institute for Fiscal Studies last month criticised Mr Cameron for omitting the first and last year of the next parliament when calculating the size of the cuts to be made.

Even if the chancellor manages to cut welfare payments by another £12bn a year, as he promised in January, this would not be enough to prevent deeper overall cuts for government departments during the next parliament.

In the March Budget documents, data show that after taking account of inflation, the coalition cut annual day to day spending by government departments by £25bn between 2009-10 and 2014-15.

The Conservatives plan to increase the pace of these cuts over the next parliament, removing another £48bn from the total, reducing the total spent in departments from £312bn in 2014-15 to £264bn in 2018-19.

So far, the public sector has coped better than many expected. But with employees more restless about slow wage growth and the easier cuts already achieved, many experts think taxes are more likely to rise than fall after the next election to protect public services and keep the deficit falling.

The OBR and the Treasury have seen the FT’s findings but both declined to comment.

Comments