‘An open door to an age of discovery’: Leo Houlding’s final Antarctic dispatch

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

True to form, the final day of our expedition was far from easy. Leaving the relatively benign terrain of the Antarctic plateau we had to cross the technical and hazardous Sentinel mountains to reach the safety of our final destination, Union Glacier Camp.

Mountain winds tend to be turbulent and erratic — not ideal for kite travel — and, combined with deep, soft snow, it took us three hours to cover just 3km. Then, suddenly the wind returned with gusto, powering us towards the pass between a row of sharks’ tooth peaks.

It took all our skill to pilot our big kites around cliffs, crevasses and walls of ice but in little more than 15 minutes, we had covered the final 3km to the col. It was like waterskiing behind a speed boat, but with no petrol fumes and much more severe consequences should one make a mistake.

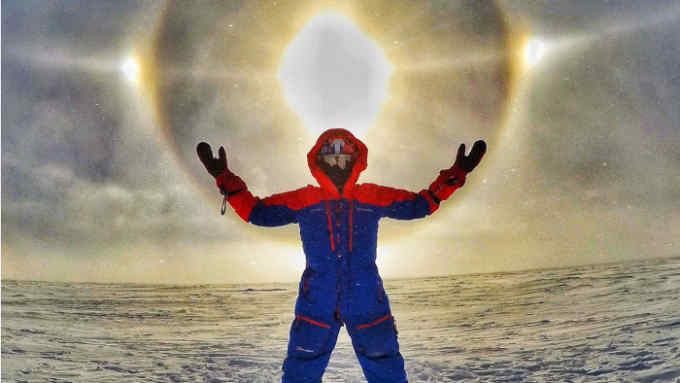

As we nervously crested the col, not knowing precisely what we would find, we were elated to see not only that the terrain ahead presented no serious hazards but that the view unfolding before us was as dramatic as any we had seen throughout the expedition. Behind us, the jagged fangs of the Horseshoe Valley and the endless white desert of the high plateau beyond. In front, a snaking glacier, winding its way down into the vastness of the great Ronne Ice Shelf.

A few hours later we glided into camp, skiing into a warm welcome from the staff and guests of Antarctic Logistics & Expeditions, the company that runs the base and the flights that connect it to Chile. It’s hard to describe the feeling of camaraderie and accomplishment to have completed such a long, complex and ambitious expedition. Not to mention the relief at securing the return of the $100,000 bond I had posted to cover possible rescue — remortgaging the family home need not be my first task on return to the world of wifi. Perhaps best of all was that after 1,760km and 51 days of extreme adventure, autonomous in the deep field of the frozen continent, the three of us were still laughing and joking like school boys. If we’d needed to, we felt in good enough physical and psychological shape to have begun the whole ordeal again the very next day. Of that I am particularly proud.

Now I sit alone in the departure lounge of Santiago airport. Mark departed for New Zealand last night, Jean and I have just said our goodbyes in good humour after 70 days in each other’s company, most of it in very close proximity.

Within just a few days, all the challenges, hardships and moments of joy seem like distant memories. Our cravings for cleanliness and comforts, so soon fulfilled. The fantasy of fresh food and cold beer at which we had been grasping for weeks, loses its fascination with shocking speed when they are once again available in abundance.

Although there is much about which we can be proud, as an ambitious perfectionist I cannot stop analysing the decisions and circumstances that led to the one failure of the trip; the fact that we did not climb the formidable south spur of the Spectre, the objective that originally inspired my quest: as technically difficult, committing and remote as any climb on Earth.

Had we climbed that route I think it would be fair to say our expedition could be classed as one of the most significant and progressive of modern times. As it stands, although the route we climbed the Spectre and the first ascent of the nearby Alpha Tower were very serious, committing undertakings, they sit a division below my aspirations and I feel such a grand claim would be misplaced.

The 2017/18 Antarctic season was a tough one in terms of weather, with many of the other big expeditions reporting exceptionally harsh and constant winds and whiteouts. To attempt the Spectre south face in such conditions would have been an unacceptable risk. It is easy to forget just how far we were pushed during the initial 20 days of the trip, where the wind never dropped below 15 knots (and regularly exceeded 30 knots), the temperature never rose above -25C and we did not see the sun for more than an hour at a time. It took great resolve and a very seasoned team to push ever further towards the edge of the Earth in such conditions. At times I felt our chances of completing the quest were dim indeed.

But it is folly to dwell on the only aspect of the mission that was not 100 per cent successful. Our experiment with long distance, upwind kiting, using high-performance race equipment, was an unmitigated success. For the dedicated few at the vanguard of 21st century exploration, we have opened a door to a new age of discovery. To travel such great distance, at such speed (up to 52km/h) with such loads (up to 215kg each) is unprecedented and our experiment with utilising one extreme adventure sport to enable another is a shining example of what I like to consider “new school adventure”. I hope we have inspired some of those who have followed us to look beyond the lauded but unexceptional “big ticket” adventures — the South Pole or Seven Summits, say — to more original trips that recapture the true meaning of adventure.

In Union Glacier camp we had the good fortune to share celebrations with a team who had pioneered a new man-haul route to the pole via the Kansas glacier. Under the guidance of the great Australian Eric Philips, one of the most accomplished polar travellers, Jade Hameister, a 16-year-old schoolgirl from Melbourne, accompanied by her father Paul, became the youngest person to claim the polar hat trick of North Pole, South Pole and crossing Greenland. But it was a comment to her father after seeing some of the footage from our trip that gives me a great sense of accomplishment. When asked if she’ll go for Everest and the Seven Summits next, she replied: “Perhaps, but honestly I’m more interested in doing some more new and different stuff, like Leo and his crew.” Mr and Mrs Hameister, please accept my apologies.

For previous dispatches and background on the expedition, see ft.com/spectre. The trip was supported by Berghaus and grants from the Wally Herbert Award and Mount Everest Foundation. A short video will be available on FT.com next month; a feature film will be released in the autumn. Houlding will be speaking at the FT Weekend Festival on Hampstead Heath on September 8

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Subscribe to FT Life on YouTube for the latest FT Weekend videos

Comments