Online privacy: a fraught philosophical debate

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Problems over the societal impact of Big Tech and social media, and their effect on values such as privacy, have long been a source of public concern.

But companies and campaigners find that resolving them involves navigating the ethics of privacy — a concept that countries, nationalities and traditions approach in very different ways.

“Privacy is a nebulous concept generally and, over the years, we have seen misplaced narratives being framed around it,” says Vidushi Marda, digital programme officer at Article 19, an international freedom of expression campaign group.

One example is the claim often made by defenders of mass surveillance that it is no threat to privacy if people have “nothing to hide”. “We see some of that changing,” explains Marda, as policymakers develop a greater understanding of the importance of privacy. This was especially the case, she says, after whistleblower Edward Snowden revealed the scale of mass surveillance by US and other western powers in 2013. Other developments that have shifted attitudes include the scandal over personal data and election influencing involving marketing group Cambridge Analytica; and an investigation by the UK’s information regulator into Clearview AI, the controversial facial-recognition system.

At the Big Tech companies, the dominant ideas about what online privacy means tend to be western-centric — perhaps unsurprisingly, given so many are American.

Nikita Aggarwal, a research associate at the Oxford Internet Institute’s digital ethics lab, compares the western tradition — rooted in Immanuel Kant’s ideas of the individual, free will and autonomy — with alternative traditions in other parts of the world that can regard privacy as belonging to communities and groups.

One approach to group privacy is the ‘data trust’ model, in which an institution acts as the trustee for users’ data, binding it to specific rules to serve the interests of its users.

For example, a 2019 pilot scheme in the UK, run by the Open Data Institute in collaboration with the Greater London Authority and Royal Borough of Greenwich, studied how sharing city data — such as the energy efficiency of social housing — could improve the south London community.

And, in a report last December, a committee of experts appointed by the Indian government also proposed a “community right over non-personal data”, involving data trusts.

“Understanding that variation [in approach] could help us . . . to think differently about the way we manage data-governed technologies,” says Aggarwal. She believes a greater emphasis on group-level privacy could allow for better data sharing to protect public safety and public health. “Maybe we need to lessen our obsession with autonomy in the west, it may not be serving our best interests.”

But group-level solutions would have to come with high standards of data protection, as well as measures to stop mission creep — which remains a risk.

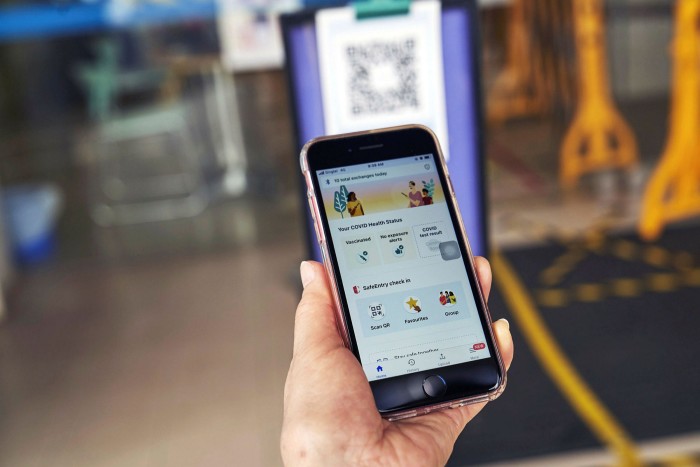

In response to the coronavirus pandemic, the Singaporean government set up a contact tracing system reliant on a central database, allowing staff to rapidly locate and contact those who may have been exposed to coronavirus. Such a trade-off in personal privacy for the public good may have been deemed acceptable during a crisis, but a change in policy now allows the police to access this data.

Marda says: “Knowledge and learnings from the so-called global south are still treated as one-off case studies, when they should be contributing towards . . . more nuanced and inclusive conversations.”

Similarly, distinctions between Japanese and western conceptions of privacy have long been examined by Rafael Capurro, former professor of information management and information ethics at Stuttgart Media University,

One key difference, says Capurro, lies in the conception of “self”. In western tradition, this idea values the individual. By contrast, in Buddhist tradition, the self is viewed as an insubstantial, illusory concept, not a fixed permanent thing to be guarded.

Attempts to impose western concepts of privacy outside the west can even cause misunderstanding, says Marda.

“It’s not just scholars,” she says. “In 2010, the Indian government . . . stated ‘India is not a particularly private nation’. This is a trope that we see pervading technical and policy documents at a global level as well.”

Marda says that, contrary to claims by the Indian government that privacy is a western concept, it is rooted in the country’s legal tradition. “While the words and narrative used may differ from western constructions of privacy, the essence of privacy was very much there.”

Academics are now putting much more emphasis on intercultural digital ethics. But it is increasingly difficult to argue that western ideals should be the starting point for ethics in government and business.

And the problem of reconciling the ethical traditions of east and west is more than just academic discourse. China and India combined have a population of about 2.8bn people, which poses practical problems for technology companies.

Aggarwal is among a group of experts working to build forums to discuss these questions. Last year, she helped organise the first symposium on intercultural digital ethics, which brought together philosophers from around the world to consider how to solve some of these challenges. “We don’t have an international treaty on Big Tech, so it is trying to help us understand why we do have and should have local approaches [to regulation],” she says.

Marda says the first step for policymakers is to focus on “local context, ground realities and cultural legacies”.

“The second is to centre these conversations around stakeholders, power and incentives; and the narratives that arise as a consequence of them,” she says. She wants scrutiny over the politics that inevitably underpin the design and structure of technologies and systems.

Capurro is optimistic that discussions around intercultural digital ethics are improving, and moving beyond the world of academic circles. “[They are] also having a large impact on society at large, through social media and particularly through a growing number of Zoom meetings open to a larger audience,” he says.

He is optimistic that a more inclusive ethical future is possible: “Different visions of privacy do not necessarily hinder a practical consensus.”

Comments