Lunch with the FT: Adrian Joffe

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

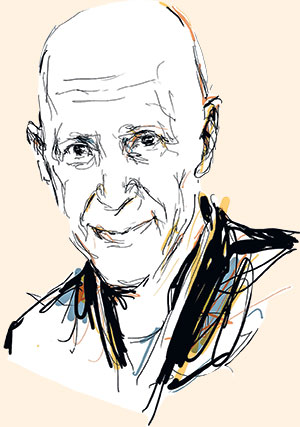

Adrian Joffe, 60, may have the hardest job in fashion. Not because, as president of Comme des Garçons International, he is in charge of all the foreign operations of a Japan-based business with annual sales of $220m but because, if there is “a cult of Comme”, the iconoclastic and hugely influential label founded by Rei Kawakubo in Tokyo in 1969, then he is its high priest. Habitually dressed in a black Comme suit and white Comme shirt, he even has the ascetic style of a disciple, complete with shaven head and skinny frame.

It is Joffe, who is also Kawakubo’s husband, who acts as the bridge and the translator between the designer and the rest of the world. It will be Joffe standing backstage next to the designer after her menswear show in Paris this evening, relaying Kawabuko’s gnomic utterances to the waiting journalists and retailers. At last womenswear season, for instance, Kawakubo, speaking through Joffe, explained the genesis of her storm-cloud-meets-astronaut sartorial constructions by announcing, “I felt the only way to do something new was to try not to make clothes.” (Try saying that with a straight face during fashion week.)

All of which makes Joffe’s choice of Manhattan’s Russian Tea Room, an over-the-top crimson-and-gold Fabergé egg of a restaurant, stuffed with caviar and high-calorie blinis, a bit counterintuitive. “But I love this place,” he says with a smile, shuffling across a deep red banquette as I arrive for our lunch. “In my previous existence, I used to come all the time,” he says, talking not about reincarnation but referring to a former job.

Though Joffe may have chosen to meet in an environment that reeks of kitschy, tsarist decadence, he clearly doesn’t feel under pressure to overindulge. He orders the business express lunch: borscht and vareniki, a kind of Russian ravioli. I choose a beet salad and gravlax from the appetiser side of the menu.

This kind of confounding of expectations is not atypical of Joffe, who has studied and practises Zen Buddhism. On the one hand, he says he feels an affinity for simplicity, on the other, he runs a high-fashion company – high fashion being for many the epitome of the decoratively unnecessary. He insists there is more congruency between the two disciplines than my raised eyebrows suggest.

“My Zen training is pretty integral to me surviving in this business,” he says. “It’s a way of understanding the world, the constantly changing nature of fashion, and how interdependent everything is.” This may sound like after-the-fact rationalisation but Joffe is entirely serious. When he is not translating for Kawakubo, he speaks quietly and hesitantly, deliberating over his words. There’s no spiel.

It is true, in any case, that while Comme des Garçons’ fashion is largely about unbalancing people – making them question their expectations of clothes and beauty – its business is balanced on a broad base of more accessible lines. These include Play, a “non-fashion” line of T-shirts and basics that is one of its bestselling collections, and Shirt, made in France, and largely based on shirts. “The main line is the engine of the company, the inspiration,” explains Joffe, “but we know it is not for everyone.”

It is also true that Joffe’s life is about achieving a similar balance: between work and home; Europe and Japan; the imperatives of commerce and creativity, and being part of a company that, as he puts it, “breaks all the rules – but also is part of the industry”. Not that any of it was planned. “I thought I would be a diplomat,” he says, as our first course arrives. “Or an academic.” He swirls his soup. “I don’t know if I can eat,” he mumbles. “I get nervous talking about myself.” He is, after all, part of a company that has built some of its reputation on opacity.

Joffe says that one of the things Kawakubo has taught him is: “Never answer a question directly.” Or, rather, to answer any question “the way you want”, which is to say: not necessarily in a way that responds to what was asked. And even though I know we are talking theoretically, this makes me pause with a piece of beetroot halfway to my mouth.

…

Adrian Joffe was born in South Africa in 1953 and raised in Johannesburg along with his older sister, Rose. His father was a pharmacist and the family moved to London when Adrian was eight. After school, he attended the School of Oriental and African Studies and majored in Oriental studies, focusing on Tibet, but “I was the only student, and when Margaret Thatcher came to power, she decided that was inefficient” and the department was closed. He thought about going to study in California, or of travelling around India but ended up in Japan. “I just immediately felt at home,” he says. By then his sister had started her own small knitwear company, Rose Joffe, and was looking for distribution in Japan. Joffe began helping her, licensing the business.

“I didn’t have a vocation,” he says, looking down at his soup. “So I thought, ‘Why not? Do I really want to end up a professor of Tibetan in a place like Melbourne?’ I just let things happen. I believe in karma.”

But, I ask, did he have any idea of what he was doing in business? “No,” he says, as the waiter arrives to clear Joffe’s half-eaten bowl of soup. “Sometimes I still think I should go back to school and do an MBA but then I think it’s too late. But, you know, Rei is also an untrained designer. I think sometimes it’s easier to break the rules if you don’t know what they are.” He pauses. “We break our own rules all the time.”

Before he worked at Comme, Joffe knew Kawakubo, or at least her work. “I used to see her walking her dog in the street in Tokyo,” he says, “but I never spoke to her. I also used to buy a lot of Comme. I would take all the money I made from the licensing deal and buy clothes.”

Kawakubo was already a legend at that point, having been part of the Japanese “invasion” of Paris Fashion Week in 1981. She had a profound impact on the industry, jolting it out of a focus on prettiness and challenging the status quo with dark, unfamiliar clothes. However, her business was almost entirely based in Japan and she knew she would have to break Europe to grow. “She is focused on creative first but business is a very close second,” says Joffe. “Because otherwise, what is the point?”

In 1987, a mutual friend mentioned that Comme des Garçons was looking for a commercial director in Europe and asked if Joffe was interested. “It felt like karma again,” he says, and though he was still working with his sister, he said he was interested. “Then I had to meet Rei, and they didn’t want to scare me, so they told me I would be translating. But, really, she was sizing me up the whole time.” Joffe got the job and moved to Paris. He became president in 1993.

Although Comme des Garçons International has become profitable independent of the company’s headquarters in Japan, the symbiosis between the centre and the outposts is clear. From Tokyo, Kawakubo continues to exert creative control over every element of her empire, with the directive that whatever it does, it must do in a new way. For Joffe in Paris this means having “creative business ideas”.

Before he can explain what that means, at least in Comme’s terms, the waiter delivers the next course, which in Joffe’s case consists of about three small raviolis, while I get a plate of six or seven large rosettes of salmon, arranged like a bouquet. “That’s funny,” Joffe says. “You ordered an appetiser but it’s much bigger than my main course.” I go back to the meat of our conversation, asking him to expand on what he means by “creative business ideas”.

“For me,” he says, eating his ravioli, “it’s how can we sell in a new way? The guerrilla stores, for example.” These were a series of early pop-up shops, operating between 2004 and 2011, for which Joffe “gave” dead stock from his warehouse to fans in cities where there were no existing Comme des Garçons stores. He also gave the fans a few rules: they could not spend more than $2,000 on a shop, the stores could not be run by fashion people, and they could only stay open for a year. “I mean, I really had nothing to lose, right?” he says. “I had this stock sitting around doing nothing. This way, if it worked, it was almost all upside.” Largely, it did work. In total, 37 stores, requiring almost no investment, popped up in cities from Berlin to Singapore and Reykjavik. The guerrilla store concept ended when others started to copy it.

Another creative idea is the “partial licence” for Comme des Garçons perfume owned by Spanish beauty group Puig. “They came to me,” Joffe says, “and said they wanted to license the perfume. And I said no, but I would grant them a partial licence. And they said, ‘There is no such thing.’ ” So Joffe created two companies, Comme des Garçons Parfums, which owned the rights to the second fragrance he made, and Comme des Garçons Parfums Parfums, which owned all the others. He licensed the former to Puig and now, he says, “they sell to department stores, and we sell to everyone else, and it works really well.” The perfume business is responsible for revenues of about $10m a year.

Then there are the Dover Street Markets, Comme des Garçons-owned emporiums in Tokyo, London and, as of last month, New York. Unlike traditional single brand stores, DSM mixes big and emerging names to create the equivalent of high-end market stalls under one roof. The end result is not so much about Comme des Garçons products as the brand’s point of view. Each DSM is slightly different; the New York store, for example, is 20,000 sq ft over seven floors – selling everything from the Comme brands to Prada (for the first time), Thom Browne, Jil Sander and Nike – and featuring freestanding dressing rooms and a great glass elevator like something straight out of Roald Dahl. Like the guerrilla stores, it is well off the beaten retail track, a long way down Lexington Avenue in a neighbourhood otherwise populated by inexpensive Indian restaurants.

“We like the idea of ‘poor luxury,’ ” says Joffe. “Plus we can’t afford Madison or Fifth or SoHo; the prices have gone berserk. This was an old Jewish college. It has some humility and history. Rei always says that we can’t copy ourselves.”

…

Joffe refers to his wife and boss often in conversation, quoting her almost like a catechism: “Rei always says, ‘We need luxury brands, we need H&M [with whom Comme collaborated in 2008], everything has a purpose, even if their way is not our way’”; “One of Rei’s favourite words is ‘common sense’ ”; “Rei said I could do perfume if we did a new one every year.”

They became personally involved in 1991, and were married in Paris in 1992. “I think the people in the company were surprised but they were also happy for us,” Joffe says. The couple decided early on to keep work and private life as separate as possible – “we are very strict about that” – and not just when it comes to themselves. “Rei encourages everyone to leave their personal problems at home,” he says, adding that families tend to stay out of the office.

Joffe is based in Paris and Kawakubo in Tokyo but he says he goes to Japan about 10 times a year, and she comes to Europe four or five times. “It has its advantages and disadvantages,” he says. “Our life together is never mundane except when we are on vacation.” They talk “about 10 times a day”. They both like biographies and travel, and have been to Ukraine and Yemen together on holiday. In addition, Joffe boxes to stay in shape with a trainer. “I love it. It’s physical, emotional, about multitasking, defence, attack . . . ”

Isn’t that very non-Buddhist? “No, I don’t think so,” he answers, and laughs. “Buddhists are always whacking the table when they debate.” He whacks the table, too, to demonstrate. A waiter looks over, alarmed. Joffe is wearing a Cartier ring that Kawakubo gave him in the shape of a nail – she has a matching one.

He says there is no question that at work Kawakubo is his boss and he is her employee. After all, she does own almost the entire company; he says this also means she owns the “risk”. The way he sees it, he’s protected.

“I have a tendency to want to make people like me,” he says. “Rei is very direct, and has very little patience with false compliments, which has been a good example for me.” Especially, he acknowledges, because a large part of his job is about saying ‘no’, and “I hate disappointing people.” People sometimes try to use him to get to her but “she has very good intuition about that”.

The waiter comes to take our plates – all the ravioli has disappeared – and asks if we want dessert. Joffe says: “Oh dear, no, I couldn’t eat another bite,” but when I say I might have some fruit, he orders an espresso. “You know,” he says, “Rei likes people with a point of view. It doesn’t have to be her point of view. Caroline Kennedy [the new US ambassador to Japan] came to the store in Tokyo, and Rei was very happy. Caroline Kennedy has her own style, and Rei likes that.”

As I eat and he drinks, I ask if he thinks he has a hard job, being pulled between his wife and what the outside world thinks, or assumes, about her. “No, not at all,” he says. “It’s just what I know. But I also can’t imagine working anywhere else.” He pauses, as I ask for the bill, and then adds: “Not that I’ve ever been headhunted for anywhere else.”

We both consider the possibility. Joffe laughs. “We have our own special place in the system,” he says. “Can you imagine a world where there was only Comme des Garçons? It would be terrible. We all have our role to play.” It’s a benediction of sorts, I suppose.

Vanessa Friedman is the FT’s fashion editor

——————————————-

The Russian Tea Room

150 West 57th Street, New York, NY 10019

Express lunch, including borscht and vareniki $40.00

Beet salad $18.00

Gravlax $24.00

Bottle of still water $8.00

Bottle of sparkling water $8.00

Espresso $8.00

Total (incl tax and service) $135.41

Comments