Uri Levine shepherding his Israeli start-ups into billion dollar unicorns

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Uri Levine could, if he wanted to, be doing something else — or, indeed, any number of other things.

The Israeli entrepreneur co-founded Waze, the traffic and mapping mobile app that disrupted the in-car navigation business and now has more than 50m users. He and the company’s other shareholders sold the company to search giant Google for a reported $1.1bn in 2013 in one of the country’s biggest high-tech “exits”.

Levine will not disclose how much he made from the sale; Globes, the Israeli business publication, estimated at the time that his stake was 3 per cent and he netted about $38m. It is safe to say that the deal made him very rich indeed.

Yet instead of retiring early and indulging in his hobbies — he is an avid cyclist and skier — Levine has been involved in six other start-up companies, all with a common denominator: to save ordinary consumers time and money. “Doing a lot of good for a lot of people is the only thing I care about,” Levine told the Financial Times at the Herzliya office of Feex, the highest-profile of his new ventures. And by “good”, he says he means, “if I can save you money, if I can empower you, if I can make things accessible to you that were not accessible”.

Levine is one of a new breed of Israeli entrepreneurs who are holding on to their start-up companies for longer and shepherding them into the billion-dollar-plus valuation league known to investors as “unicorns”. If they do sell, they are increasingly ploughing their know-how and money into new companies and becoming serial entrepreneurs.

Whereas Waze, with its driver-generated maps, obviated the need for expensive satellite navigation devices for its users, Feex is aiming to return to consumers some of the money investment managers charge for their retirement and other funds. In the US alone, these fees add up to about $600bn a year, Levine says, more than twice the size of Israel’s GDP.

Feex, which advises users on how to switch their investments into lower-fee vehicles, is advertising itself as “the Robin Hood of fees”.

Levine’s other companies follow a similar theme: he is also involved in Zeek, an online marketplace for unused store credit, and Roomer, which allows people to sell and buy non-refundable hotel reservations. He is a board member at Moovit, a company that aims to do for public transportation what Waze did for cars.

Another of his companies, FairFly, allows users to rebook plane tickets at a lower cost if the fare falls after their original booking. Engie allows customers to use a smart phone to diagnose what is wrong with their car, then feeds back mechanics’ quotations, taking some of the mystery and murk out of car repair.

“The mission is solving big problems for consumers. In many cases, these are things I ran into accidentally,” Levine says, wearing a black Feex T-shirt and sunglasses perched on his grey hair. “The gap between consumers and the industry is big and dramatic, and there is a huge opportunity for disruption.”

In a country where many of the top 1 per cent indulge in large homes and lavish habits, Levine keeps a low profile. He lives in a rented flat in Kfar Saba, near Tel Aviv, riding his bicycle to most places; for longer trips, he drives his Alfa Romeo Giulietta or his children’s Renault Clio. “In general, I don’t believe in spending more than you’re making,” he says.

While frugal in his own habits, Levine has grand ambitions for the new companies where he is chairman or a board member. He believes that some, while destined to remain small start-ups in their first few years, could become “unicorns” as they succeed in solving big problems and one day be acquired for $1bn or more.

This is something new for Israel. The country nicknamed “start-up nation” has a reputation for producing world-beating technology companies: Israelis pioneered antivirus software and invented the memory stick, and are grabbing a disproportionate share of the new cybersecurity industry. Israel’s high-tech military is a famous incubator for talents; Levine did his own military service in Unit 8200, Israel’s cyber spy agency.

But the country’s groundbreaking entrepreneurs are also famous for their impatience. Historically, they have been better at generating new ideas than building their companies into national champions. Venture capital groups and industrial investors from America, Europe and increasingly China, are always scouting for new opportunities in Israeli technology and are ready buyers of fledgling companies. “If you are a first-time entrepreneur, it is a difficult dilemma: a $50m-$100m exit is a life-changing event for an entrepreneur in their 20s or 30s,” says Gadi Tirosh, managing partner of Jerusalem Venture Partners (JVP), Israel’s biggest venture capital fund.

No longer. Israel’s high-tech sector, now 25 years old, is producing entrepreneurs, such as Levine, who are experienced and confident enough to scale up their companies into the billion-dollar league. Waze’s sale to Google set a new benchmark, or in Levine’s word, a “target”, for Israeli tech, tempting other company founders to hold on for longer.

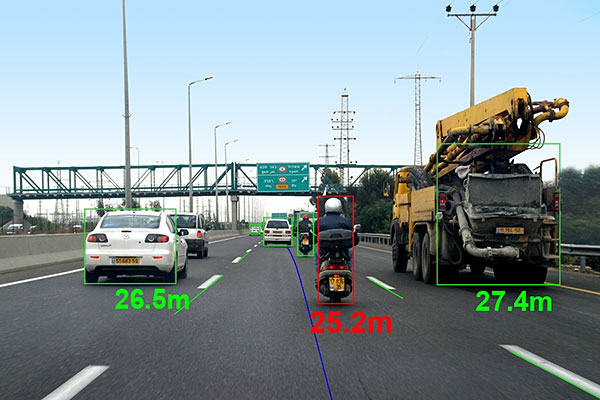

Another member of Israel’s new billion dollar-plus club is Mobileye, a Jerusalem company that has captured a commanding share of the world market for devices enabling autonomous driving, with its cameras that help vehicles to brake, park, and drive themselves.

Investors in CyberArk, a cybersecurity company in which JVP was an early investor, chose to build the company in Israel and list its shares on New York’s Nasdaq rather than sell to a big technology group. IronSource, an online software and mobile distribution company, was recently listed as worth $1.1bn as of August 2014 on a Wall Street Journal list of “the billion dollar start-up club”.

When founder-entrepreneurs do sell, they are more likely to do so at a higher valuation and use the company to create new concerns with bigger ambitions. “Israeli entrepreneurs are getting more experienced, more mature and want not just to make money, but to actually make a mark,” says Rubi Suliman, high-tech leader at PwC in Tel Aviv. “We are seeing more and more of these.”

Mobile apps and the cyber-world have helped to level the field in Israel’s favour, given the ease with which mobile technologies can be tested and rolled out in foreign markets, with the help of small teams in the US, Europe or elsewhere.

Israel’s small size — just 8m people — was traditionally seen as a drawback in the drive to create successful big companies. Levine, however, thinks the country’s companies are at an advantage vis-a-vis their American competitors, as they are more likely to go international straight away rather than focusing on the local market.

He joined Waze’s two other founders in 2007. The app’s breakthrough concept, which Levine today compares with Wikipedia, the crowdsourced encyclopedia, was to use the collective wisdom of drivers and the GPS functions in their phones to create maps.

Building the critical mass and working out kinks in the technology took time. The first, rudimentary version of Waze worked on a Nokia phone. The company launched in Israel and the US in 2009, then in the rest of the world in 2010. As it went global, the company’s partners spotted areas where it was not good enough: Israel has no ferries and few tunnels, so it needed to find a solution for what to do when a user’s GPS disappears.

In 2012, says Levine, everything changed. “As soon as you become good enough and free, you win,” he says. Should Levine and his partners have held onto Waze longer and built an even bigger concern? PwC’s Suliman is doubtful. “Waze is an application that is very difficult to monetise if you are not Google or Facebook,” he says. “It had to be sold.”

Notwithstanding its exit, Waze remains part of Israel, where it has about half of its 200 global staff, most of whom work on research and development. “Google owns us, but we are largely autonomous and have our own office space,” a company representative says.

Of Levine’s Feex venture, he says he got the idea for it in 2009, during the global downturn, when the funds in his own investment portfolio lost 20 per cent of their value, on top of which, he says, he was charged “a lot of fees”. When he approached the funds’ managers, he succeeded in having them reduced.

Feex’s main focus is the US, where the majority of its 25 employees work out of a New York office. The service vets users’ portfolios and makes recommendations for similar investments with lower fees. The company says it has more than 30,000 users in the US and more than 100,000 in Israel. Feex aims to earn its keep through commissions it makes when it refers customers successfully to alternative investments.

The company grew out of the Zell Entrepreneurship Programme, an academic course at IDC Herzliya, where Levine mentored a team of students charged with solving “a big enough problem we could address”.

Roomer, the marketplace for non-refundable hotel room reservations, came out of the same school year. The company allows users to sell bookings they are unable to use, and collects a percentage per transaction.

Levine hints that he is not finished yet. The medical care industry, he says, is another sector where consumers are “getting ripped off” and is ripe for disruption.

“We are doing more and more,” he says. “I am not finished with the revolutions I want to start — there are so many.”

Comments