ESG investment favours tax-avoiding tech companies

Simply sign up to the ESG investing myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

More on ETFs

Visit the FT’s ETF Hub for news and analysis, investor education and tools to help you select the right ETFs.

The huge rise in environmental, social and governance-based investing is funnelling money into companies that pay less tax and provide fewer jobs than many counterparts with lower ESG ratings, analysis shows.

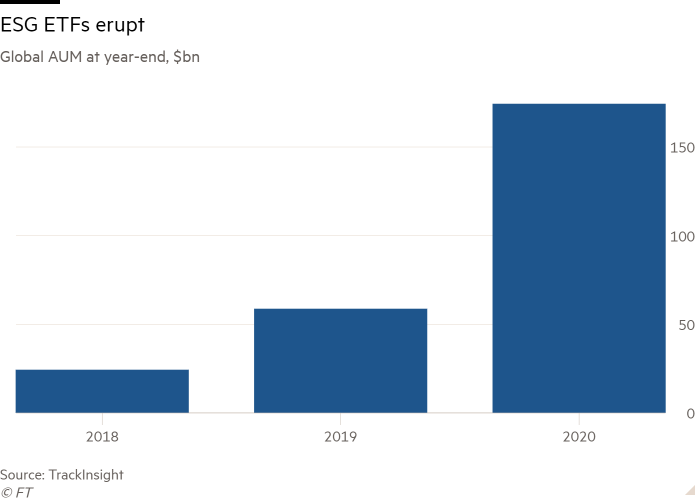

Assets under management in ESG ETFs jumped three-fold from just under $59bn at the end of 2019 to $174bn at the close of 2020, according to data from TrackInsight, an ETF data provider.

Yet while the ESG movement is driven by a stated desire to improve the world by tackling issues such as climate change and board composition, it is arguably exacerbating other fissures in society.

“ESG funds are unconsciously worsening the social and political crisis associated with automation, inequality and monopolistic concentration,” said Vincent Deluard, global macro strategist at StoneX, a New York-based brokerage.

“I doubt that the unfolding crises of the 2020s can be averted if the ESG movement’s ultimate effect is to funnel more money into tax-avoiding tech monopolies, pharmaceutical giants with few workers, and financial networks,” he added.

“Despite its noble goal, ESG investing unintendedly spreads the greatest illnesses of post-industrial economies. As ESG ratings increasingly determine the allocation of capital, we must pay attention to the kind of companies they reward.”

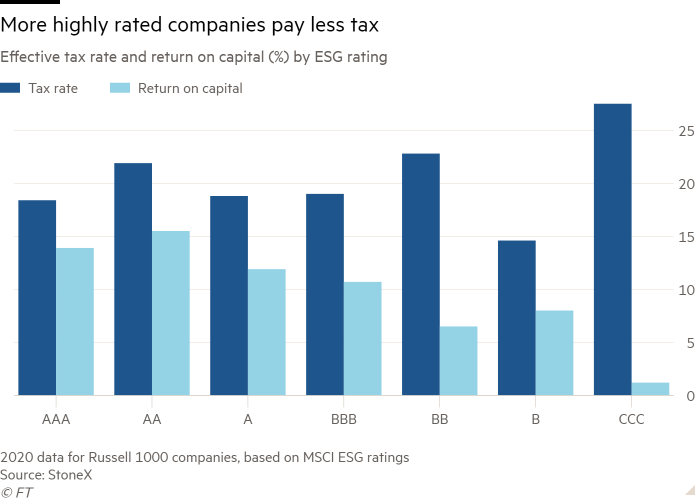

Deluard’s analysis found that companies with high ESG ratings pay much less tax than their lower-rated peers.

US-listed Russell 1,000 companies with the top triple-A ESG rating from MSCI, for example, paid an average tax rate of 18.4 per cent last year, while triple-C-rated firms typically paid 27.5 per cent.

“There is an almost perfect inverse relation between companies’ ESG ratings and their effective tax rate,” said Deluard.

The discrepancy is likely to be partially driven by sectoral effects, with ESG funds skewed towards technology companies, which arbitrage differences in tax regimes between the countries in which they operate in, minimise their tax liabilities via transfer pricing and have a lot of intangible assets, which they can locate in the most favourable tax jurisdiction.

Microsoft, for example, is rated “best in class” in most ESG metrics, helped by having a human rights policy, a biodiversity policy and plans to be carbon negative by 2030. Yet it has paid an effective tax rate of 16 per cent over the past eight years, he said, compared to the 47 per cent paid by triple-C rated Universal Health Services.

“Big tech’s profits are so massive that a small increase in tax compliance would do more social good than all the remarkable initiatives touted in their glossy corporate social responsibility reports,” said Deluard.

He argued taxation was a “blind spot” for the ESG industry as a whole with, for instance, only five of the 551 ESG metrics available on the Bloomberg platform, sourced from MSCI, related to taxes (although some other tax data are available via companies’ income statements).

Bloomberg declined to comment, as did a number of other ratings providers and ESG fund managers approached for this story.

Deluard also claimed that ESG investors were “winning their unintended war against people” by shunning labour-intensive companies.

Comparing a “virtuous 15” of the stocks most overweighted versus the S&P 500 in the 15 largest US ESG equity ETFs to an “ugly 15” of the most underweighted companies, he found that the former, which include Apple, Microsoft and PepsiCo, employ just 1.9m people, against 5.1m for the latter, which include Walmart, Philip Morris International and Boeing.

The average “virtuous” company has 20 per cent fewer employees than the median Russell 3,000 company, despite having a larger market capitalisation than the typical S&P 500 stock.

Last year, “the best [investment] strategy would have been to do exactly what ESG ETFs unconsciously do: sell companies with lots of employees and buy ones with lots of robots, patents and intellectual property”, Deluard said.

He described this as “the dark secret” of ESG investing. “The single most salient characteristics of these funds is that they favour machines and intangible assets over humans.”

Moreover, he argued this was a feature, not a bug, of ESG. “Companies with no employees do not have strikes or problems with their unions. There is no gender pay gap when production is completed by robots and algorithms.”

In order to tackle these issues, Deluard proposed that ESG metrics should be adapted to incorporate how many workers a company employs, relative to market cap.

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here

“You should acknowledge that a job in itself has value, before you even talk about what sort of job it is.”

Further, he argued that ESG should be expanded to ESGT to incorporate taxation as a fourth pillar.

“How about taking the amount of tax they pay and just rewarding companies that pay a lot,” he said. “Part of being a good global citizen is that you pay taxes and those taxes help to solve problems.”

However, Deluard feared there would be pushback from much of the business community if this approach was adopted.

“You can get a company to try and protect the environment or have more diversity, it doesn’t affect the bottom line, but to make them pay more taxes . . . Right now, they have a legal duty to pay as little tax as they can.”

Click here to visit the ETF Hub

Comments