How London’s popular restaurants could be raising property prices

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

The estate agent window, like the front of a restaurant, is a place to stop and fantasise. The latter can tell you a lot about an area: if it is hard to book a table, it may also be hard to buy a property. But while the link between food businesses and property prices is not straightforward, there are some intriguing examples of property price hikes following restaurant openings.

Twenty years ago, Fergus Henderson and his business partner Trevor Gulliver were shown the site of an old bacon smokehouse at the fringe of Smithfield Market in central London. The address had already served as an oil merchant, brandy distillery and 17th-century pub – The Swan with Two Necks – but never before as what they had in mind: a restaurant.

Squatters had been evicted, and the building was derelict, says Gulliver: “unlettable”. But he wasn’t put off. Gulliver had already transformed the Fire Station by Waterloo into a crowded bar and restaurant in the 1980s, when the area was down at heel. As he toured the Smithfield site, bacon stoves still visible, he had one thought: “It’s got to be done.” St John restaurant opened in 1994 with two other restaurants in the area for company, and not much else, save for a brothel and a cinema, which later burnt down.

In the decades since, a revolution has been wrought on London’s food scene, as seemingly inexorable as the rise in property prices. A Steak in the Economy, a study produced this year by the food start-up foundation Kitchenette, reported that five new restaurants are opening every fortnight in London, and that the sector’s employment growth in the UK was the “highest of any industrial grouping in 2011”, employing some 400,000 Londoners. Smithfield itself teems with places to eat and drink, with expensive apartments to match. On nearby Cowcross Street three-bedroom flats in Denmark House (the former headquarters of Danish Bacon) are being marketed by Cluttons for £2.5m.

Liam Bailey, global head of residential research at Knight Frank, has analysed the property price increases within a 250-metre radius of some of London’s finest restaurants from 2003 to 2013. For St John the increase was 81 per cent. Around central London, prices near Michelin establishments such as Marcus Wareing at the Berkeley, have increased by as much as 150 per cent. “Many of those restaurants in the W1 and SW1 postcodes outperform our prime central London index, which over same period rose by about 129 per cent,” says Bailey.

The eastern part of London has undergone huge changes – but can a good restaurant effect this change alone, or at least initiate it? “St John, [St John] Bread & Wine and the Fire Station have been seen catalysts [for an area],” says Gulliver. “You’ve got to be brave . . . street grime is sometimes a good thing. It doesn’t have to be Dickensian, but it helps to show something real – edgier sites have value to the customer.”

Bailey says a “strong restaurant and retail offer is taken for granted” in established areas such as Mayfair. “When you look at the City fringe, Farringdon and Borough, the restaurant offering is particularly important to the residential market,” he says. “That’s where new investments by restaurateurs and retailers begin to make a difference. You get people who trailblaze and the gentrification starts to begin, and, for most people, the tangible signs of that are aspirational restaurants and retail.”

This idea is ratified by the success of other restaurants established in new territories at the same time as St John; “an age of adventure,” says Gulliver. The Eagle opened in Clerkenwell in 1991, after breweries were forced to sell off tenanted pubs by the Monopolies Commission. Paul Driscoll, director at Hurford Salvi Carr estate agents, estimates that residential values in Clerkenwell have risen from about £200-£300 per sq ft in 1996 to about £1,000 per sq ft today, although those prices have been given a fillip by Crossrail. “There was no residential [in Clerkenwell in 1996] . . . Shoreditch was similar, so those values have increased more pro rata.”

Fish! in Borough Market was established in an 18th century pea-shelling warehouse in 1999; the rent, for 3,000 sq ft, was a modest £60,000 per annum, according to Trevor Watson, director of valuations at Davis Coffer Lyons, the specialist leisure property consultants. “When [Fish!] first opened Borough Market was the back end of nowhere. It was genuinely a ‘pump-priming’ restaurant, built in what was then an old-fashioned fruit and veg market. Vinopolis was another primer, but it was in the middle of nowhere – there were no tourists at all.”

Conran Restaurants’ 1991 Le Pont de la Tour, in Butler’s Wharf, was a similar story of seeding a food business into a barren landscape, in this case an old dockland site. Yolande Barnes, director of residential research at Savills, specialising in regeneration, says Le Pont de la Tour was a “key part of a creative hub”. The rise in property prices in the area since then has been steep. “[After 1993] average prime residential prices increased by 263 per cent before the 2008 peak,” says Barnes. “This compares with 231 per cent for Wapping across the river, which lacked the vibrancy created by the mix of uses at Butler’s Wharf.”

Setting up a restaurant in an unlikely location can sometimes be an expression of shrewdness, as well as courage. Big infrastructure projects such as Crossrail, or Tube extensions, can alert canny developers and restaurateurs to early opportunities.

Sam Harris opened his modern trattoria Zucca in 2010 in a quiet spot at the lower end of Bermondsey Street. Soon, the street was abuzz: José Pizarro opened his tapas bar in 2011, and White Cube Gallery followed in the same year. “When I moved [to SE1] there was hardly anyone around,” says Harris. “Even four, five years ago it was such a different area.”

Crucially, he spotted that the Zucca site would have strategic advantages. “It’s accessible to the City, 10 minutes in a taxi, it’s two minutes to the river, and I was aware of all the regeneration around the Shard and London Bridge station . . . I couldn’t figure out why there wasn’t a really good hub of eating around here.” Harris decided to open with the calculation that lunch trade would be prepared to hop in a taxi to reach him, and even now, with the “property boom” in the area, locals are outnumbered at the restaurant’s tables. “An old estate agent friend of mine used to joke that Zucca had added £20-£30 [a week] to rents,” says Harris. Average residential property values in Bermondsey Street have risen 79 per cent since 2003, according to Knight Frank.

In Brixton and Hackney over the past few years, council involvement has helped to make food central to complex changes in the areas. Lambeth council gave free three-month leases to sites in Brixton Village in 2009, and a flowering of restaurants catering to a young, hip demographic soon followed. Some restaurateurs had already spotted the area’s potential, with Franco Manca moving into Brixton Market in 2008 before opening branches in Chiswick and Balham.

In Hackney, the regeneration programme has food as its “cornerstone”, according to the Kitchenette report. But, as ever, it is a difficult story to delineate. “I don’t think opening a restaurant on Wilton Way has made it a more desirable place to live; it’s been like that for the past five years, definitely in comparison to how it was 15 years ago,” says Claire Roberson, owner of Mayfields restaurant. “People say the hipsters and rich middle classes are moving in but a lot of the changes are from within Hackney.”

Place-making by landlords is also key to urban change, and applies to high-end areas as much as unloved, grittier ones. In Mayfair, for example, the Grosvenor estate worked for a long time to improve Mount Street. “It’s taken six years for Mount Street and Motcomb Street to become established retail destinations,” says Helen Franks, head of retail and commercial lettings at Grosvenor. “The catalyst was Marc Jacobs deciding to open, and the refurbishment of Scott’s in 2006. We started to work with other retailers to position them on the street.” While Richard Caring’s Scott’s is held on a head lease, so not directly under Grosvenor’s control, it has been instrumental in adding glamour (and gossip) to the street.

Peter Wetherell, managing director of Mayfair specialist Wetherell Properties, believes that “signature” restaurants, such as Scott’s, can add value to residential addresses nearby. He compares the sales value before and after Caring’s sister restaurant, 34, opened. “We sold an identical flat in June 2011 [on Grosvenor Square] for £2,709 per sq ft and then the flat above in January 2012 for £3,166 per sq ft – an uplift of 17 per cent.” It is hard to prove a direct link, but certain streets in Mayfair do seem to have blossomed thanks to nearby restaurants.

“In the old days you wouldn’t dream of buying a property over a restaurant,” adds Wetherell. “I used to joke that I’ve sold flats over a fish and chip restaurant . . . and it’s Scott’s . . . [With the restaurant 34], Caring fought a planning battle and everyone said it would bring down the area, but it’s made the street. Again, all the residents were up in arms – they’re all in there now.”

Natalie Whittle is associate editor of FT Weekend Magazine

——————————————-

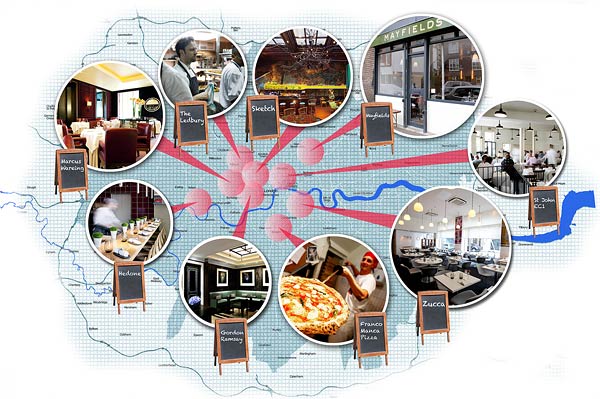

The price rise menu

Growth in property prices from 2003 to 2013 for areas within a 250-metre radius of the following restaurants in London:

● Marcus Wareing at The Berkeley, in Knightsbridge 150%

● Sketch (The Lecture Room & Library), in Mayfair 143%

● Ledbury, in Notting Hill 138%

● Gordon Ramsay, in Chelsea 115%

● Mayfields, in Hackney 88%

● St John, in Smithfield 81%

● Zucca, in Bermondsey 79%

● Mayfields, in Hackney 88%

● Franco Manca, in Brixton 71%

● Hedone, in Chiswick 44%

(Figures compiled by Knight Frank)

Comments