Alma Thomas defied gravity and reached for the stars

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

In the 1960s, retired schoolteacher-turned-painter Alma Thomas glanced around at all the violence and racial injustice, and decided to fix her eyes on her garden, and then on outer space. She watched the tide of civil rights engulf the fortress of racial injustice, but it was among her jonquils, tulips and crocuses that she found joy she wanted to share with the world.

Even now, her exuberant canvases retain their ability to cheer minds buffeted by a news feed of madness and calamity. Matisse aspired to paint “a good armchair” for the tired businessman; Thomas built a breeze-blown bower where the world’s horrors could fade soothingly away. “Through colour,” she wrote, “I have sought to concentrate on beauty and happiness, rather than on man’s inhumanity to man.” Which means that just now, the Studio Museum in Harlem may be the most contented place in New York.

Thomas was the first black woman to be given a solo show at the Whitney Museum of American Art — though for most of her life she did not seem destined for artistic immortality. Born in Georgia in 1891, she was raised under Jim Crow laws. “One of the things we couldn’t do was go to museums, let alone think of hanging our pictures there,” she remarked on the eve of her Whitney retrospective in 1972. “My, times have changed. Just look at me now.”

Her family fled racial violence, chasing a better life to Washington, where they moved in 1906. She lived out her years in the same house, and died there in 1978. The first woman to graduate from Howard University in 1924 in fine arts, she taught at Shaw Junior High School, Washington while continuing to study painting, and, after retiring in 1960, launched a new, brilliant career near the end of her seventh decade. She dedicated the rest of her life to churning out canvas after radiant canvas, despite arthritis and failing eyesight.

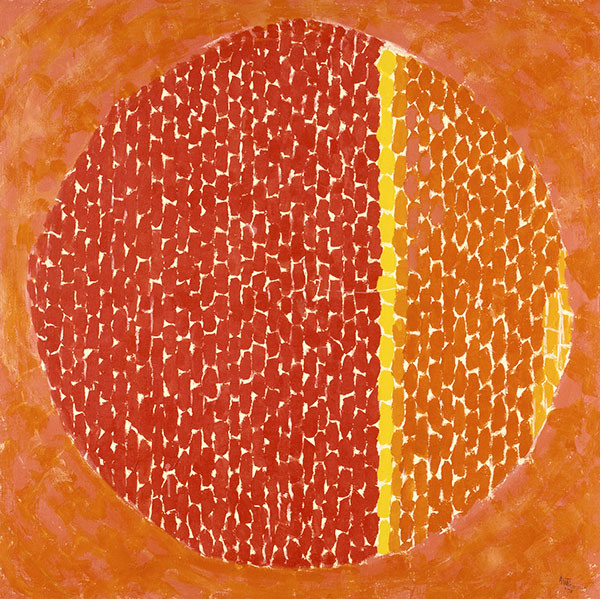

Thomas’s paintings evolved from fairly generic Abstract Expressionism to a signature (and utterly recognisable) blend of slashed and patterned daubs. Those bright little packets slide down in vertical droplets, or shoot across the canvas from side to side. Occasionally they unfurl concentrically into circle-like forms. More important than the brushstrokes is the white space between them, which stirs a sense of motion, like a breeze blowing through petals. At times she lifts off for an aerial view of gardens stretching out below, divvied up into rows and vivid patches. Like Monet at Giverny, she focused on the plantings of her own neighbourhood, the small yards and gardens where people poured their passions into flowers. But if you miss the vegetal and floral allusions, you might see the paintings as experiments in pure colour.

Thomas resisted the pressure to take her politics to the canvas. As cities blazed, and as the fight for equality turned toward more violent means, many black artists channelled their rage on to politically charged canvases or transfigured it into furious assemblages. To forge ahead with abstraction seemed to like a sellout to some, who dismissed it as “white art in blackface”.

When her mind did tear loose from her own house’s gravitational pull, it catapulted far beyond crime, racism, riots, or war, and vaulted straight into the heavens. Born before the Wright brothers’ first flight, she was awed by the possibilities of space travel. “Today not only can our great sciences send astronauts to and from the Moon to photograph its surface and bring back samples of rocks and other materials, but through the medium of colour television all can see and experience the thrill of these adventures. These phenomena set my creativity in motion.”

They sure did. From her imaginary spaceship, she looked back at her home planet and saw it as a toy, a patterned quilt, or a teeming ball of fire. In “Snoopy Sees Earth Wrapped in Sunset” (1970), the usually blue-green globe has become a rusty sphere, with the border between red shadow and orange daylight scored by a vertical yellow line. “Starry Night and the Astronauts” (1972) depicts the blue-black sky as a set of falling drapes, while the prow of a flying ship emerges from inside a fold.

These charming cosmoscapes depict nature as a tiled surface, tempering her wild visions, burning skies and purple horizons with the evidence of rational assembly. One of her concentric paintings — “Resurrection” (1966) — hangs in the Obama White House, a great wheel of nested colours exploding towards a hot yellow sky, the motion at once exuberant, irresistible and terrifying.

To October 30, studiomuseum.org

Comments