Abe’s legacy in Africa under scrutiny at development summit

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

On the day of Shinzo Abe’s assassination in early July, Akinwumi Adesina, the president of African Development Bank, mourned the death of Japan’s longest-serving prime minister by calling him “a great friend of Africa”.

“He drove Ticad [the Tokyo International Conference on African Development] for a very strong Japan-Africa partnership,” Adesina said in a condolence message posted on social media, referring to the investment conference held every three years to discuss African development.

Abe had stood out among a long series of Japanese prime ministers who had come and gone without an apparent concrete interest in Africa. When he returned for a second term as premier in 2012, he revamped the country’s policy on Africa in a bid to show why Japan remained relevant, despite China’s overwhelming presence in terms of both manpower and financing capability.

As part of that effort, Abe reshaped Ticad to focus more on attracting private-sector capital following a contraction in Japanese official development assistance. With promises of a boost in corporate investment, Japan sought to reposition itself as a business partner for Africa, instead of simply a donor, according to Keiichi Shirato, a former journalist and expert on Africa at Ritsumeikan University.

Abe also brought his vision of a “free and open Indo-Pacific” to the continent, trying to distinguish Tokyo from Beijing by pushing for the rule of law, human rights, freedom and democracy. “Instead of having an isolated foreign policy on Africa, former prime minister Abe applied in Africa the same principles promoted in the Indo-Pacific and Asia,” Shirato says.

But, as the eighth Ticad takes place in Tunisia this weekend, Japan’s investment record in Africa is once again under scrutiny. Originally drawn to Africa to win UN votes, Tokyo now has a much more urgent need to engage with the continent, given the global hunt for rare metals and other commodities.

For companies wrestling with shrinking populations at home, chief executives in Japan are also attracted to the potential for expansion in one of the world’s fastest-growing regions.

A few businesses, including Toyota Tsusho, which has 22,000 employees in Africa, have been successful through a mix of organic growth and aggressive acquisition of local companies. On the back of accelerating vehicle sales, revenues at the Toyota Africa unit exceeded ¥1tn ($7.5bn) in its last fiscal year — a first for a Japanese company.

“Africa has about 20 or 30 vehicles per 1,000 people, compared with an average of 500 to 600 in developed countries,” says Toshimitsu Imai, executive vice-president at Toyota Tsusho. “Even if that grows to 100, that would be five times the number of vehicles now, so there is nowhere else in the world with this much growth potential.”

For many other Japanese businesses, however, Africa remains a challenging and alien market, and Abe leaves a mixed legacy on his repeated pledges to boost investment by Japanese companies to $20bn over three years.

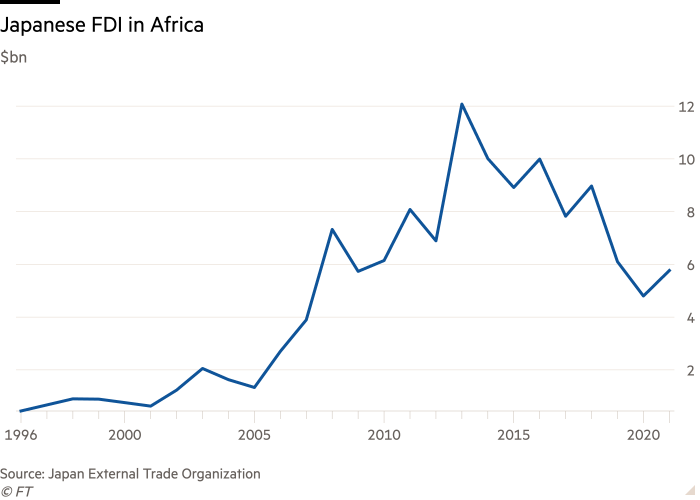

According to the finance ministry, Japan’s foreign direct investment (FDI) to Africa fell from $12bn at the end of 2013 to $5.8bn last year. That was even as FDI flows to Africa reached a record $83bn in 2021. Among the top 10 investors in the continent, the UK accounted for $65bn of foreign assets in Africa, while the US held $48bn in FDI stocks, and China held $43bn, according to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.

“There are only about 8,000 Japanese people in Africa, while there are an estimated 1mn people from China — the level . . . is far too different,’’ says Ryuichi Kato, vice-president of Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), which funds international development. “Japan is also a relative newcomer, while China has a longer history in Africa.’’

After three decades, Ticad, which in recent years has drawn as many as 11,000 participants and an entourage of senior Japanese leaders, is also struggling to redefine itself. Prime minister Fumio Kishida, who will attend virtually after testing positive for Covid-19, plans to strengthen Japan’s investment pledge with a focus on start-ups and green technology. With a hybrid live and online format due to Covid, numbers attending in person are expected to be down.

Critics say Japan needs to move beyond the unrealistic ambitions for private-sector investment and focus more on where it can actually deliver to promote African development.

For Kato, that means going back to Ticad’s roots of encouraging self-sufficient growth in African countries and long-term partnerships in projects for sustainable infrastructure, such as roads and water systems, as well as food-supply chains and green energy.

Those efforts will be even more important in light of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which has pushed up the costs of food, energy and other daily goods — adding to the pressure on Africa’s already fragile economies.

For Kishida, the success of Ticad will also be measured by whether he can convince the African governments to deliver a unified message of condemnation against Moscow. So far, the response of African nations has been mixed, with 17 of the 54 countries on the continent having abstained from the UN vote to condemn the invasion, while eight simply did not vote at all.

“The invasion of Ukraine has threatened food and energy supplies, and the international community must show solidarity with Africa,” Kato says.

“This is now the timing for us to deliver action and, in that sense, Ticad is very important.”

Comments