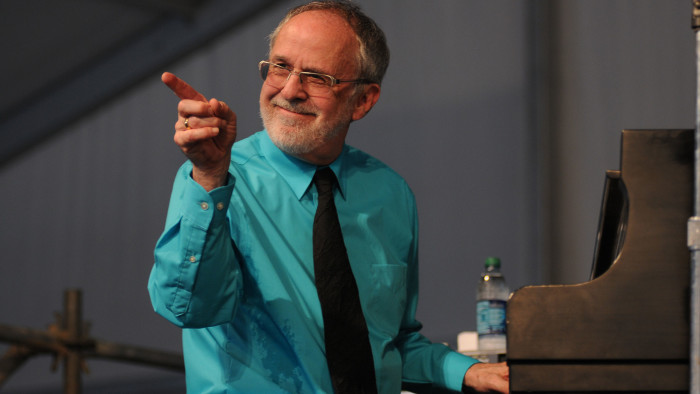

Bob James and David Sanborn play at the Barbican

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Raise the subject of smooth jazz with Bob James, and you are likely to spark a degree of irritation – a surprising reaction, perhaps, from the man often dubbed “the godfather of smooth jazz”. But there is more to the American pianist and composer than his contributions to this artfully crafted, commercially successful and resolutely unadventurous genre would suggest.

James arrives in Britain this month for a date at the EFG London Jazz Festival alongside saxophonist David Sanborn. They are playing material from new album Quartette Humaine, a soulful and funky acoustic project far removed from the bland radio-fodder that characterises smooth jazz.

The London gig follows platinum sales for the album and nearly 40 shows. Good though the recording is, James tells me when we meet in San Francisco that the band has grown looser and more adventurous with each performance.

“Both of us have been a little bit frustrated with the direction that commercial jazz has gone, and the way that things get pigeonholed,” he says. He freely admits to a smooth side – “If I didn’t like the smooth tunes, I wouldn’t have made them” – but says it has been taken out of context. “What happened was that the programme directors or consultants who were starting this [radio] concept chose only the smooth cuts from some of us. We as musicians don’t believe we deserve to be typecast just as that.” Now, he says, “I’m working on becoming the godfather of rough jazz too.”

James and Sanborn last collaborated 25 years ago on Double Vision. Although the album was a bestseller, the pair never toured together. But they stayed in touch, vaguely kicking about the idea of a second album until they ran into each other at the Tokyo Jazz Festival a few years ago. “We had a little jam session thing,” James remembers. “Something clicked, and we decided it was time to take it more seriously.” Released in May, the new album has topped both straight-ahead and smooth jazz charts.

James and I are chatting backstage at Yoshi’s Jazz Club before a gig with Fourplay, a jazz-funk quartet who first recorded together in 1991. The set is full of opulent sounds and lean-but-classy grooves. You can hear why commercial radio seized on some elements of James’s music – but just as a falsetto vocal or sparse tinkling line threatens to get too smooth for comfort, the rhythm tightens, a texture changes or a long, dig-deep solo bursts into life.

This exceptional control has been a long time in the making. Born in the small town of Marshall, Missouri, James was three when he started to play the piano. Formal music education continued at the University of Michigan, when he became active on Detroit’s jazz scene. He won first prize at the 1963 Notre Dame Jazz Festival, impressing Quincy Jones, who was on the judging panel, so much that he recommended the young pianist for a first record deal. James moved to New York, recorded the album Explosions for the avant-garde label ESP, and spent three years on the road with Sarah Vaughn. Soon after, Jones asked him to play on his 1969 album Walking in Space and write a couple of arrangements. It was this that drew the attention of producer and CTI label boss Creed Taylor.

Under his guidance, James used a love of classical music to produce the opulent textures and astringent voicings on a string of classic jazz recordings. Taylor also fine-tuned James’s ear for a top-class rhythm team. “The tune had to have a groove. If it didn’t have a groove, it didn’t make any difference what your melody was,” he says.

You see the same names cropping up time after time on the rhythm credits of James’s albums. Both Harvey Mason, the drummer with Fourplay, and Steve Gadd, who plays drums on the new project with Sanborn, are long-time collaborators who appeared on James’s early recordings.

James’s elegantly crafted grooves have been sampled for countless hip-hop recordings: “Take me to the Mardi Gras” alone has been sampled 43 times to date. “There’s some magic in those rhythm sections that hip-hop producers could relate to and wanted to take little chunks of,” says James. But, he adds, “very simply, it was theft.” Although licensing structures are in place now to protect copyright, he still resents having to police the use of his work.

At 73, an age when he might be slowing down, James is still driven by playing and performing. “I love it,” he says. “That 90 minutes that I’m performing on the stage is the highlight of my life . . . As long as I’m playing with great musicians such as this, I hope I never have to stop.”

——————————————-

EFG London Jazz Festival, November 15-24

Bob James and David Sanborn play at the Barbican on November 16

Comments