What will happen to all of Britain’s empty shops?

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

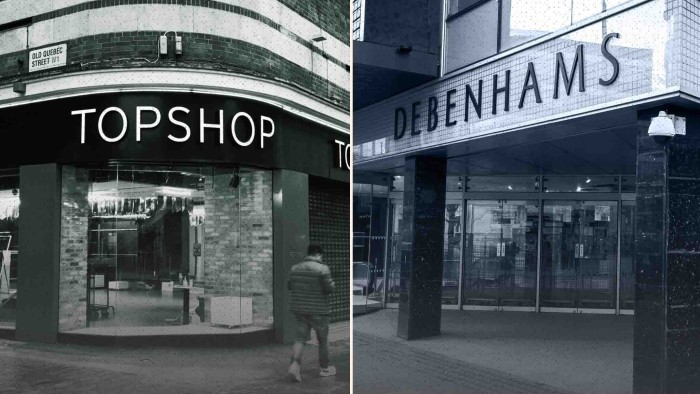

The collapse of Debenhams and Arcadia has magnified a problem for landlords: what to do with the glut of redundant retail space tainting Britain’s towns?

Neither Boohoo nor Asos, which have picked up Debenhams and Arcadia brands including Topshop, Topman and Dorothy Perkins, have opted to take on the leases for the shops.

That means almost 15m square feet of space — equivalent to roughly 200 full-size football pitches — will hit the market in England and Wales, according to property adviser Altus Group.

The struggles of retailers and restaurants to make bricks-and-mortar pay, coupled with the migration of shoppers online, means vacancy rates in town centres were already high.

Some sites will be taken by different retailers. Others could be repurposed. But many are likely to languish, with no economically viable alternative use, unless local councils or the government intervene.

Landlords would prefer to re-let the properties — and are rushing to line up viable tenants.

Shopping centre owner Hammerson has been reducing the number of Debenhams stores in its portfolio since before the crisis. In Reading and Croydon, units once filled by the chain have been taken by fashion retailer Next, which has outperformed most high street rivals through the pandemic.

Hammerson has also had some success in re-leasing Debenhams units at its out-of-town retail parks, a relative winner over the past year.

British Land, the FTSE 100 property owner, has also been trimming Debenhams and Arcadia stores from its £12bn portfolio, and is in talks with other retailers about filling the space.

Potential new tenants include discount stores B&M and Home Bargains, as well as fashion brands that have performed better during the pandemic, such as Zara, Mike Ashley’s Fraser Group and JD Sports, which last week announced plans to raise almost £500m as part of an expansion drive.

Debenhams sites are harder to fill than the individual units left behind by Arcadia, because of their larger floor space.

Allsop, the auction house, recently sold a Coventry shopping centre anchored by a Debenhams for £4.9m. Eight years ago — when the department store still had allure — the mall was valued at £37m. At this month’s auction, the presence of the store put a number of bidders off, said George Walker, partner at Allsop.

The buyer intends to keep the shopping centre for its current use. But retail cannot fill all the vacant lots: there are too many sites available and a dearth of demand.

Casual dining chains, which picked up hundreds of former retail sites during a private equity fuelled boom in the 2010s, have been equally knocked by the crisis, with almost all of the major national chains cutting down their estates.

“The high street has been dying a slow death for years now and this crisis has just accelerated it,” said Graziano Arricale, operating partner at the private equity firm Oakley Capital, who independently bought the London brasserie Langan’s out of administration in December.

In the absence of like-for-like demand for the empty space, landlords are increasingly looking at repurposing sites — something the government has been quick to encourage.

One solution for ghostly town centres is “experiential leisure” companies, which are betting on pent-up demand for social activities when lockdowns end.

The 80,000 sq ft former Debenhams store in Wandsworth, for example, has been taken on by the trampoline company, Gravity, in a £4m joint venture with the landlord Landsec and investment company Invesco. The site will have a Japanese-themed electric go-karting area, bowling lanes, pool, darts and crazy golf.

Other leisure groups are looking to snap up sites vacated by department stores on London’s Oxford Street, many of which could become mixed-use venues with some retail, a larger contingent of leisure businesses and offices on the upper floors.

Chris Adams, chief executive of Otherworld, an immersive virtual reality experience, said the company was “getting loads of [sites] thrown at us” with landlords offering rents as much as 30 per cent below previous levels and sweetener deals such as paying for some of the upfront development costs.

But Thomas Rose, a property adviser to several major leisure operators and developers, said that despite gym and leisure companies actively looking for sites, there were still too many to fill. “People who keep talking about trampoline parks have got their head in the sand. It is a much deeper problem than that to solve,” he said.

Another possibility is that dead shops and restaurants are reborn as flats. The government is considering rolling back rules on commercial-to-residential conversions — a controversial move that opposition groups say risks littering high streets with low-quality housing.

Housing should be part of a balanced high street, argued Tony Brooks, managing director at Moda Living, a rental property developer. A block of flats would bring more visitors to local shops, he said.

But, he warned “these schemes don’t chuck out profit on day one”. Planning, procurement and construction can all take years.

While the conversion to rental flats is economically viable in major regional cities, “in the poorer towns, local authority and government support will need to bridge the viability gap,” added Brooks.

Some have argued that barren high streets need to be reimagined entirely. In Stockton-on-Tees, in the north-east of England, the local council is exploring plans to knock down the vast shopping centre that dominates the high street and replace it with a riverside park.

With a land bridge, potential for a new public library and a large lawn for outdoor events, the proposals have been touted as the most radical blueprint for a town centre to date. If successful, other councils may follow Stockton’s example, rather than looking to repurposing.

This article has been amended to clarify that Graziano Arricale independently bought Langan’s out of administration in December.

The current nationwide lockdown rules in England

The main restriction is a firm stay-at-home message

People are only allowed to leave their home to go to work if they cannot reasonably do so from home, to shop for essential food, medicines and other necessities and to exercise with their household or one other person — once a day and locally

The most clinically vulnerable have been asked to shield

All colleges and primary and secondary schools are closed until a review at half-term in mid-February. Vulnerable children and children of critical workers are still able to attend while nursery provision is available

University students have to study from home until at least mid-February

Hospitality and non-essential retail are closed. Takeaway services are available but not for the sale of alcohol

Entertainment venues and animal attractions such as zoos are closed. Playgrounds are open

Places of worship are open but one may attend only with one’s household

Indoor and outdoor sports facilities, including courts, gyms, golf courses, swimming pools and riding arenas, are closed. Elite sport, including the English Premier League, continues

Overseas travel is allowed for “essential” business only

Full details are available on the government’s official website.

Letter in response to this article:

A farming solution for all those empty shops / From Wes Wilcox, Addingham, West Yorkshire, UK

Comments