Drugmakers respond to growing need for eye treatments

Simply sign up to the Pharmaceuticals sector myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Of the five senses, none may be more precious than sight. Yet even as other areas of medicine have advanced rapidly in recent decades, the area of eyecare has been comparatively static, especially when it comes to developing new drugs.

“Eyecare between the 1980s and early 2000s was essentially the domain of surgeons, who were eventually helped by lasers,” says Dr Bernard Gilly, the chief executive of GenSight Biologics, a Paris-based company developing gene therapies for eye diseases.

In recent years, eyecare research has had something of a renaissance, however, thanks to the combination of escalating need for treatments and some important scientific discoveries.

By 2050, the number of people with visual impairment or blindness is set to double to more than 8m in the US alone, according to official figures. “Novel approaches are being tested across all the major ophthalmology conditions,” notes Dominic Trewartha, an analyst at healthcare investment specialist GBI Research. He estimates that pharmaceutical companies are developing almost 160 first-of-a-kind drugs to treat everything from diseases associated with ageing, such as macular degeneration and glaucoma, to rare genetic conditions that cause blindness in younger people.

The runaway success of two drugs that treat a form of age-related macular degeneration, known as wet AMD, has lifted drugmakers’ spirits. Lucentis, sold in a partnership between Swiss pharma groups Novartis and Roche, generates billions of dollars in annual sales, as does Eylea, which was discovered by New York-based biotech Regeneron.

“The very big success of these two drugs has clearly pulled the domain of eyecare to the forefront,” says Dr Gilly.

Several conditions still have no treatment, such as dry AMD. Roche is testing one potential treatment, Lampalizumab, in late-stage clinical trials. Nonetheless, Umer Raffat, analyst at investment banking services adviser Evercore ISI, says: “We’re hearing a lot more about eyecare recently, much more than we did, say, two or three years ago.”

He points to the approval of a new drug for dry eyes, Xiidra, made by Shire, the Anglo-Irish drugmaker, which is expected to become a blockbuster medicine, defined as one with sales of a billion dollars a year and more.

The rise in activity has led to more dealmaking in eyecare. The past decade has brought $20.9bn of licensing deals, where larger pharma groups buy the rights to drugs developed by smaller companies. There have been a further $12.9bn of development agreements, where drugmakers pursue a new medicine in partnership, says GBI Research.

Among the most active companies has been Allergan, the maker of wrinkle smoothener Botox, which has one of the world’s biggest eyecare franchises. In August, the company bought ForSight, which makes a so-called periocular ring — a device that rests on the eye under the lids. The hope is to use it to administer Lumigan, a glaucoma treatment at present available as an eyedrop.

Such a device could help combat poor adherence — patients not taking their medication regularly enough — which is a big obstacle to tackling glaucoma. The majority of patients are elderly and many forget to use their eye drops. Glaucoma is expected to affect more than 80m people worldwide by 2020 and has the potential to become one of the leading causes of blindness. It might also help Allergan protect its revenues earned from Lumigan, which is anticipated to lose patent protection in the next decade.

Large companies are not alone in leading the charge. As with other areas of the industry, it is often smaller biotech groups that are developing the most exciting treatments. Shares in Aerie Pharmaceuticals, which is testing a glaucoma treatment, have jumped by more than 200 per cent in the past six months, after success in clinical trials paved the way for Aerie to seek approval for Roclatan. When added to another drug, Latanoprost, Roclatan reduces the pressure caused by glaucoma, which can lead to blindness if left unchecked.

Perhaps the most exciting area of eyecare is the emerging field of gene therapy, whereby genetic material is inserted directly into a person’s cells in order to treat or prevent a disease. The eye is “an almost perfect target for gene therapy”, Dr Gilly says. “We are born with a pool of retina cells that are not renewed in our lifetimes. So when you transfer genes into those cells they will probably last for the rest of our lives — and it is quite easy to inject genetic material directly into the eye.”

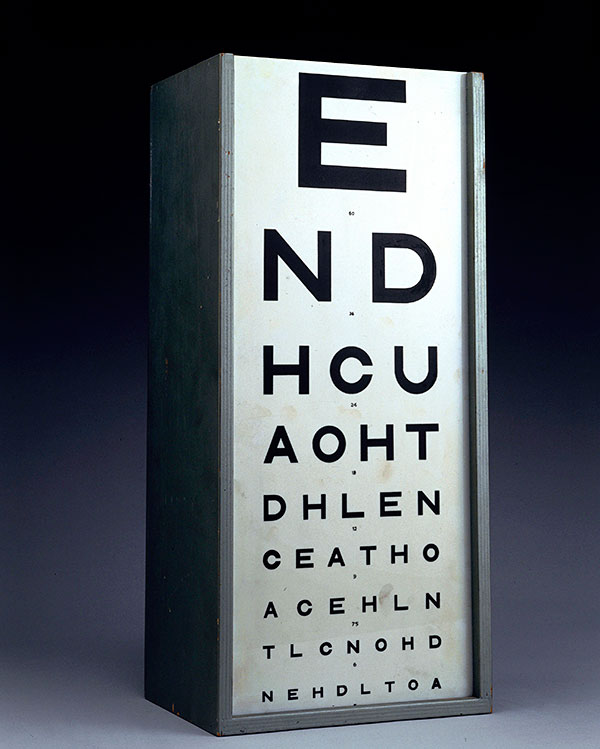

GenSight Biologics has just started a late-stage clinical trial of a drug for Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy, which affects people aged between 15 and 25. It is a brutal, sudden disease causing vision loss in both eyes, with a 98 per cent probability that sufferers will experience complete loss of vision within a year. It affects more than 1,400 people a year in Europe and the US. In a smaller study, GenSight proved the drug could restore vision to the extent that patients were able to read three lines of previously illegible letters on a chart similar to that used by most opticians.

Such an improvement in letter reading is the gold standard for companies aiming to secure approval for drugs for vision loss but some believe it is not ideal for people with severe forms of blindness. For many of these patients, the ability to make out objects and colours, and to avoid bumping into things, would be a life-altering improvement. The US Food and Drug Administration has therefore recently approved some more creative clinical trial designs.

Spark Therapeutics, a US company developing gene therapies, is testing a treatment for a rare retinal disorder in a late-stage clinical trial. Rather than letters on a chart, it uses a functional vision test where people are asked to make their way around a maze without walking into various objects.

Big questions remain about the long-term success of gene therapies and there are signs that their effectiveness may fade after several months. Yet some large pharma groups appear ready to dip their toes in the water. Allergan recently paid $60m to buy RetroSense, a small gene therapy group that aims to restore light sensitivity to people with the disease retinitis pigmentosa.

Comments