Can plasma and antibody therapies help as world awaits Covid-19 vaccine? | Free to read

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Nine months into the coronavirus pandemic, scientists are conflicted about the use of convalescent plasma and antibody therapies to battle Covid-19 while a fully tested vaccine remains under development.

The US Food and Drug Administration last month awarded an emergency authorisation for the use of convalescent plasma to treat coronavirus in hospital patients, only for a panel of experts convened by the US National Institutes of Health to hit back last week, citing insufficient evidence to support its use.

Convalescent plasma — the antibody-rich fluid left behind when all the cells are filtered out of blood — has been used successfully for more than a century as an emergency treatment in epidemics, from the 1918 Spanish flu through to the 2014-16 Ebola outbreak in west Africa.

First trialled in the 1890s by the German scientist Emil von Behring to treat diphtheria, researchers took blood from animals that had recovered from the disease and injected it into infected humans. His first clinical tests showed a positive response in 77 per cent of cases.

But nearly 130 years later, no randomised controlled trial of the therapy — the gold standard for drug testing — has been completed and some scientists remain sceptical of its long-term use in the global fight against Covid-19.

One concern is that convalescent plasma might contain other components, which could provoke a negative reaction once injected into another patient. Others argue that it is very hard to create a reproducible product given that patients generate different antibodies, at different concentrations.

“Is the juice worth the squeeze?” said Myron Cohen, professor of medicine, microbiology and immunology at the University of North Carolina. “Convalescent [plasma] is a bridging mechanism before we have more targeted treatments,” he added.

Randomised controlled trials are now under way around the world. None have released results yet but David Roberts, professor of haematology at Oxford university, which is running the biggest study in the UK, described plasma treatments as “incredibly valuable”.

Latest coronavirus news

Follow FT's live coverage and analysis of the global pandemic and the rapidly evolving economic crisis here.

So far 25,000 people have donated their blood to Oxford university, and more than 360 are involved in the study, Prof Roberts said, adding that “all of the existing evidence is consistent with there being an effect but we need to prove it”.

“What we don’t know is what dose will be effective, or who will benefit the most,” he added.

Antibody therapies

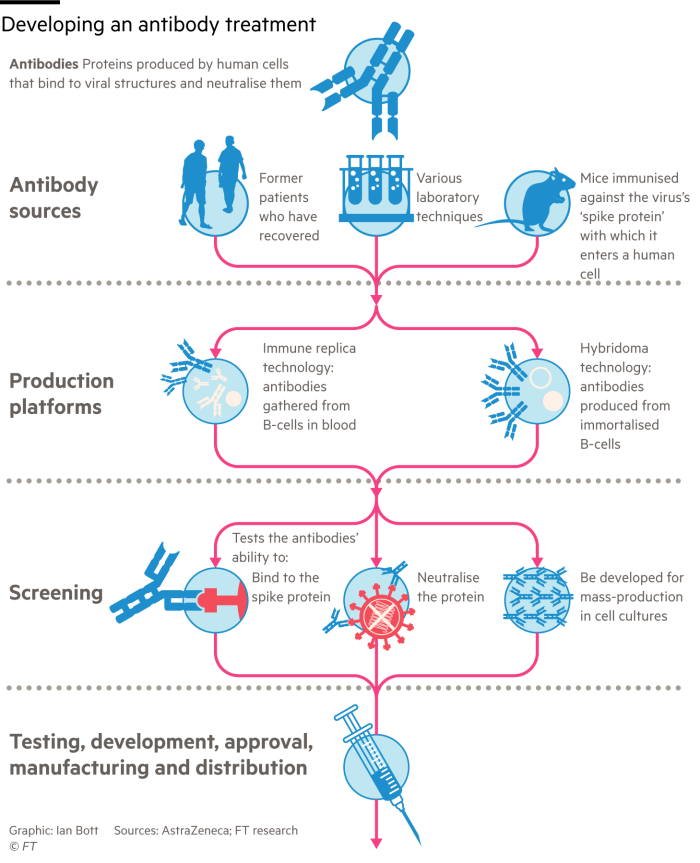

Other research groups are using more advanced technologies to clone specific neutralising antibodies, which can then be injected into vulnerable groups to protect against the virus.

The therapy, known as monoclonal or “designer” antibody treatment, is one of the fastest-growing fields in biomedical research, and is used widely in the treatment of cancer and autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn’s.

“Vaccines usually take a few weeks to have an effect whereas neutralising antibodies hit your bloodstream immediately,” said Dr Dan Skovronsky, chief scientific officer at US pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly, which has been working on the development of monoclonal antibody therapies for Covid-19.

Eli Lilly’s first antibody was isolated from a recovered patient who travelled to the US from China in late February. “We found the best antibody we could possibly find,” Dr Skovronsky said.

There are at least 50 monoclonal antibody therapies currently in clinical trials around the world. Eli Lilly expects to have the first results from its trials this month.

“I’m hopeful that they will work,” said Alain Townsend, professor of molecular immunology at Oxford university. “There’s a good chance that, given early, a neutralising antibody will alter the course of the disease.”

Unlike convalescent plasma, which is preferred as a treatment rather than a preventive drug due to the potential danger of transferring foreign blood into healthy but vulnerable patients, researchers believe monoclonal antibodies could be deployed as a prophylaxis.

The therapy could also be used to treat the early stages of infection but, as the disease progresses within a patient from a respiratory to an inflammatory illness, experts say treatment will need to shift towards drugs like steroids.

One of the problems with monoclonal antibody treatments is cost. The median price in the US for a year’s treatment for diseases like cancer ranges from $15,000 to $200,000, according to the Wellcome Trust, a British research charity. As a result, 80 per cent of such therapies are sold in the US, Europe and Canada.

“The number of people who would be able to receive them is very low compared to convalescent plasma,” said Prof Townsend, though he added: “I think that well-chosen monoclonals are more likely to work.”

Cocktail treatments

Another challenge for such treatments is the capacity of the virus to mutate, changing its genetic make-up around the part known as the spike that antibodies attack.

“I expect relatively quickly there will be mutations that develop in that region,” said David Stuart, professor of structural biology at Oxford university who is leading the UK’s Covid-19 research on antibody therapeutics.

The solution for doctors treating viruses like Ebola has been to deploy a cocktail of neutralising antibodies rather than a single antibody. “Even if it escapes one, it would be hard to escape two,” said Professor Stuart.

Eli Lilly is experimenting with cocktail therapies, along with companies including Celltrion and Immunoprecise Antibodies, even though for the treatment of influenza monoclonal antibodies in general have previously been found to have limited effect.

“In the face of difficult odds, knowing that most of the time we try we’ll fail, we still get excited,” said Eli Lilly’s Dr Skovronsky. “If you have a 5 or 10 per cent chance of saving people’s lives, you’ll try it.”

Comments