Schools face calls to boost environmental teaching

Simply sign up to the Climate change myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

The weather in Texas may have cooled since the recent extreme heat, but the temperature will be high at the State Board of Education meeting in Austin this month as officials debate how climate change is taught in Texas schools.

Pat Hardy, a conservative member of the board who sympathises with the views of the energy sector, is resisting proposed changes to science standards for pre-teen pupils. These would emphasise the primacy of human activity in recent climate change and encourage discussion of mitigation measures.

“In the national standards, everything has to do with climate change — that’s very lopsided,” she claims. “There are as many scientists working against all the panic of global climate change as there are those who are pushing it. Texas is an energy state and we need to recognise that. You need to remember where your bread is buttered.”

Most scientists and independent experts sharply dispute her views. “What millions of Texas kids learn in their public schools is determined too often by the political ideology of partisan board members, rather than facts and sound scholarship,” says Dan Quinn, senior communications strategist at the Texas Freedom Network, a non-profit group that monitors public education. “They casually dismiss the career work of scholars and scientists as just another misguided opinion.”

Such debates reflect fierce discussions across the US and around the world, as researchers, policymakers, teachers and students step up demands for a greater focus on teaching about the facts of climate change in schools.

A study last year by the National Center for Science Education, a non-profit group of scientists and teachers, looking at how state public schools across the country address climate change in science classes, gave barely half of US states a grade B+ or higher. Among the 10 worst performers were some of the most populous states, including Texas, which was given the lowest grade (F) and has a disproportionate influence because its textbooks are widely sold elsewhere.

Glenn Branch, the centre’s deputy director, cautions that setting state-level science standards is only one limited benchmark in a country that decentralises decisions to local school boards. Even if a state is considered a high performer in its science standards, “that does not mean it will be taught”, he says.

Another issue is that, while climate change is well integrated into some subjects and at some ages — such as earth and space sciences in high schools — it is not as well represented in curricula for younger children and in subjects that are more widely taught, such as biology and chemistry. It is also less prominent in many social studies courses.

Branch points out that, even if a growing number of official guidelines and textbooks reflect scientific consensus on climate change, unofficial educational materials that convey more slanted perspectives are being distributed to teachers. They include materials sponsored by libertarian think-tanks and energy industry associations.

In other countries, the pattern of climate change practices in schools is just as patchy. A study this year by Unesco, the UN agency, of educational policies and curricula in 46 member nations showed that, while 92 per cent made at least one reference to environmental themes, the depth of inclusion was very low on average. More than half of members made no mention of climate change in policy and curricula documents, and just 19 per cent discussed biodiversity. “More needs to be done to prepare learners with the knowledge, skills, values and attitudes to act for our planet,” the report concluded.

Aaron Benavot, professor of education policy and leadership at the University at Albany, State University of New York, and one of the report’s co-authors, warns that measurement remains difficult. “More and more countries are embedding into their national curricula a topic like environmental studies or ecology,” he says. “But, because climate education is not a separate subject, it’s difficult to know how much time and priority it is given.”

Deb Morrison, a research scientist at the University of Washington College of Education, favours integrating climate change into existing subjects, rather than developing standalone courses, given that timetables are already crowded and the pace of change is fast.

She stresses the importance of support to train teachers and emphasising different pedagogical styles, rather than simply distributing materials. “Without more thoughtful approaches, we’ll just have more stuff shoved on to teachers’ desks with no support,” she says. “We have a lot of accountability measures for teachers but not much money to support them teaching better.”

Pressure for further action is growing, though. David Edwards, general secretary of Education International, an alliance of teachers’ unions, says his members are frustrated that they are required to focus on other issues, while many students are missing classes to take part in activist movements, such as the school strike for climate.

A survey of 74 countries by Education International this year suggested none had made sufficient progress integrating climate change education into schools, with most efforts judged “tokenistic”.

“Environmental education was never mainstreamed,” Edwards says. “Everybody has done it outside schools. We’re 10 years from a cliff edge on climate, and students are on the streets demanding it. We need to make schools relevant so [students] want to stay, train, learn, organise and act within the walls.”

This article has been updated since publication to stress that most scientists and independent experts dispute Pat Hardy’s views

Climate change for schools

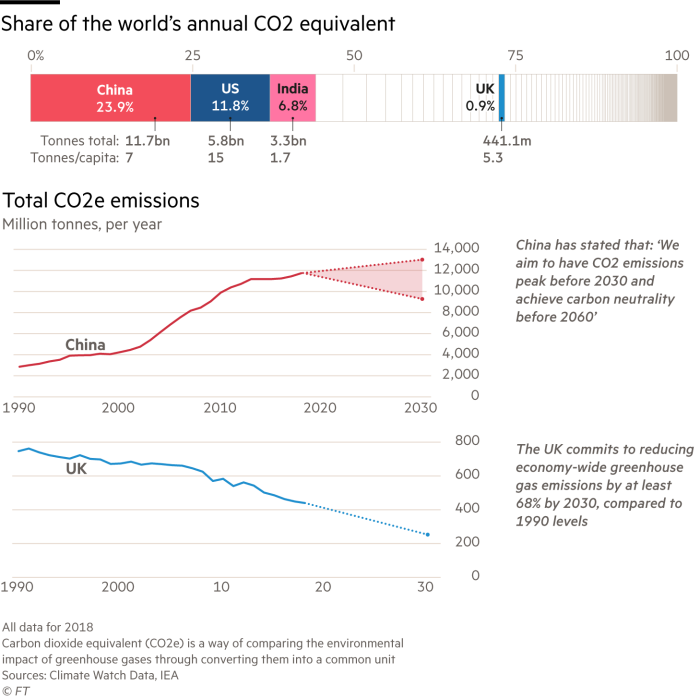

A growing number of schools are using the latest insights and data to teach climate change. For example, Alasdair Monteith, head of geography at Gordonstoun School in Scotland, suggests these questions to accompany the chart below:

Can you explain why both per capita and total emissions are useful in understanding countries’ CO2 output?

What policy proposals could explain the wide variation in projected emissions under the business as usual and conditional targets for 2030?

China produces much for export. Should emissions for these goods be counted towards its total or the country receiving them?

To what extent is the UK government’s net zero strategy for 2050 realistic?

See more at ft.com/schools

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here.

Are you curious about the FT’s environmental sustainability commitments? Find out more about our science-based targets here

Comments