David Hockney returns to LA

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

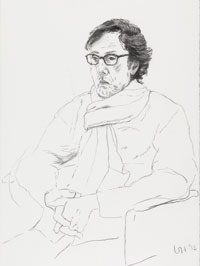

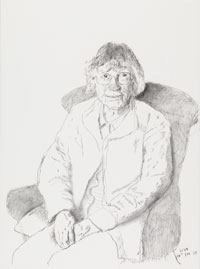

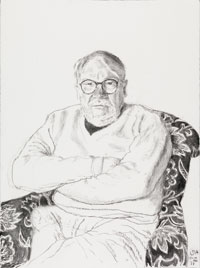

Before arriving in Los Angeles, I received a catalogue for David Hockney’s imminent San Francisco show. Every new picture from the past year was in sombre black and white. There were intimate, interior portraits of close friends; the “vandalised totem” drawings of felled and fallen trees from November; and charcoal drawings of a Yorkshire spring. “When Hockney started making these charcoal portraits, Gregory [Gregory Evans, Hockney’s friend and curator of the show] said he felt a strong sense of mortality in them,” notes an essay in the catalogue.

This wary mood about the 76-year-old artist was reinforced by Sir Nicholas Serota, director of the Tate: “This is a moment in his life when he is thinking about all of his relationships and friendships,” he said. “I found him in a reflective mood, given everything that had happened.”

“He can be very jolly and witty,” said Wayne Sleep, the ballet dancer, one of Hockney’s oldest friends. “The jokey David won’t be around at the moment. This is a very serious retrospective.”

George Lawson, Sleep’s former partner and the subject of a famously unfinished joint portrait with him (1972-75), reflected: “He’s a bit quiet at the moment. Not the usual David. And he’s had to give up smoking!”

For Hockney to be parted from his “natural, delicious, pleasure-giving tobacco”, it must be bad. I was advised I would not get much time with him and to avoid questions about events in March, when Dominic Elliott, a 23-year-old aide, died after drinking acid in Hockney’s Bridlington house.

As I boarded the plane, I was worried.

…

The winding route to David Hockney’s studio in the Hollywood Hills is timelessly preserved in his vibrant painting “Mulholland Drive: the Road to the Studio, 1980”. But it offers no real road map (turn right at the wiggly swimming pool; left at the purple sprouting tree). On arrival, there is a small gateway, almost hidden by large palm trees. Waiting behind it is Britain’s best-loved living artist, back in Los Angeles after spending much of the past eight years in East Yorkshire.

As he opens the door, the first thing you notice are his bright blue eyes, which find your face directly, with a hint of humour and curiosity. His grey hair is scruffy and he has slight grey stubble. He is wearing an old, much-loved, double-breasted Savile Row suit covered in splodges of paint and what looks like spilled tea. Underneath is a crumpled white linen shirt, red-and-white polka dot braces, finished off with faded blue corduroy shoes and a yellow-and-blue wristwatch.

He leads me via a boldly painted walkway into his sunlit studio. As soon as you are inside you feel overwhelmed by the atmosphere of creativity. There are giant black-and-white prints of the charcoal drawings I’d seen in the catalogue. But the real surprise is the new portraits, done in just the past few weeks, in strong LA colours – swimming-pool aquamarines and turquoise blues. On a single wall you can read the duality of Hockney’s twin homes – Yorkshire and LA – as well as his emotional journey of the past year.

The change from Yorkshire has clearly been energising. “I feel I couldn’t have done them in England,” he says, fondly scrutinising the portraits, which are in the acrylic paint he first used when he came to LA more than 40 years ago.

“And these grew. I didn’t plan them, really. I mean I did once I’d got three done, three or four, but they just grew and that’s what happens to me sometimes – I might plan something and then do something else totally different. I react to the people. I mean, these are just my friends, really … Then I put them up and we realised the colour was doing marvellous things to the black and white, and I made a row of them. And now, I just go on. They just keep growing.”

During our two-hour interview he laughs often and infectiously. “You don’t mind me smoking, do you?” he asks, reaching for a Camel Wide. “You see, on the cigarette packets here they don’t have the warning: ‘Death awaits you.’”

…

There has been keen interest in David Hockney’s return to Los Angeles. Having come back to Yorkshire like the prodigal son, there was a sense of loss, almost betrayal, among some of his admirers, who fear a self-imposed exile. In August, an inquest into Dominic Elliott’s death attributed it to misadventure.

“I imagine he moved over because of the show, not because of what happened,” says George Lawson. “Everyone wants to read something into it, as if it is something strange and exotic but it is not to do with the drama. It is a very sad situation that the boy is dead but there is no intrigue.”

“I was always coming back about now,” Hockney says, “because of the San Francisco show, of course. But the light here is different. Of course it is. It’s 10 times brighter, although it’s pretty good in Brid by the sea. But here it’s amazing. When I first came back I drew the garden but then I didn’t and I started that painting of …”

He hesitates as he points to a portrait of his assistant Jean-Pierre Goncalves De Lima, with his head bowed solemnly in his hands. Pinned up on the wall nearby are copies of Van Gogh’s “At Eternity’s Gate”, of a man in a similar posture, used as inspiration “… With his hands on his head – we were all feeling a bit like that. And then I did another one of JP standing but he had a lot of anguish in his face.”

This is Hockney’s only allusion to recent events. A more powerful way of understanding this work is closer to home: his own mortality. He had a small stroke last October in London. “I was there, at his home,” says Gregory Evans, who was the first to notice the change – both in his person, and in his art. “He couldn’t finish sentences. You would ask him a question and he would start to answer then would get stuck. I found the drawings he did in December seemed so changed. There was more definition in everything.”

Hockney recalls: “The first drawing I did after the stroke was the cut totem. They were very detailed drawings. I wasn’t speaking that much then but I thought, so long as I can draw and paint I’m OK, I’m all right. I don’t have to talk much anyway.”

His recovery has been slow, but steady. His voice, with its barely altered Yorkshire accent, is quiet but firm. His head constantly bobs around, energetically. It feels as if he is constantly ready to pounce on an opportunity to be bemused or to laugh – usually at life; more often at himself.

Hockney has long been interested in the impact of sensory frailty on artists. Upturned on the table next to him is a card: “Old Age ain’t no place for Sissies.” He has grown increasingly deaf (just like Goya) and exploits it to sidestep questions he doesn’t want to answer and to avoid parties. “I’m too deaf to be very social, actually. I can’t be in rooms with more than six or seven people if they’re all talking because I get a cacophony in my head and I leave and just go home. So I don’t go out much now. I go to bed at nine o’clock.”

His deafness has influenced his art. “For most people, if you know a sound is over there, you know it’s over there. I can’t tell the direction of the sound of anything now. I feel I’m seeing space clearer. If you’re blind you use sounds to locate space, don’t you? And I’m using it the other way now. I don’t mind; I think it’s rather good. I think it’s rather exciting seeing space better, I do.”

He has thought deeply about the ageing Monet, who, with his sight fading, closely observed his lily pond for his late paintings. “I sat there [in Monet’s garden at Giverny] by that lily pond and smoked a cigarette like he would have done and looked at it for five minutes. If you do that, you’ve got an awful lot in your head if you’re Monet. And it’s amazing what very short-term memory can do. Often, when I’d done these drawings I’d done them outside mostly, but then I’d just finish them a bit inside, just to do this or that from memory. You do it only in the first 10 or 15 minutes when you come in. But you can train your memory.”

Perhaps five minutes of short-term memory is all you need? Was he fearful after his own stroke?

“Not when I started to draw, I wasn’t. I just thought if I can’t speak I can speak in another way – draw, just draw. I’ll quote Picasso; he said he always felt he was 30.”

But how old do you feel now?

“Thirty, and I do, actually. Meaning, when it comes to work, I do. I’m slower than I used to be and I go to bed at nine o’clock. But when I’m painting, I still stand to paint all day. I feel OK, I mean deep down in my being I think I’m OK … I get up and work and I’m just drawing and painting now and that’s it. It’s all right. But I live the same way.”

…

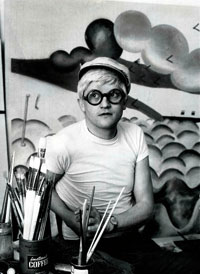

Being tucked up in bed at 9pm is a world away from the Hockney who epitomised swinging London in the 1960s. In his recent book Becoming a Londoner: A Diary, David Plante recalls “Hockney’s world” in 1966. “He bought a gold lamé jacket and a gold lamé shopping bag to carry his shopping from the local supermarket, and with his hair bleached and his large round black spectacles, he has become an icon of the times, with photographers flashing photographs of him on his way back from the supermarket.”

Since then, Hockney has socialised with everyone from Andy Warhol to the Hollywood elite. He tells me he dined at the White House with Ronald Reagan when Princess Diana danced with John Travolta but then highlights his lack of pomp by noting he rejected a chauffeured car to get him there.

But what unites the young and old Hockney is his tremendous work ethic, and a simple obsessive love of painting and drawing, instilled in him growing up in Bradford in the late 1930s and 1940s.

He wanted to be an artist from the age of 11. A scholarship boy at Bradford Grammar School, he sabotaged his academic career in order to take more art classes. One of his English reports from the 1950s, at age 13, is published in David Hockney: My Early Years: “He still does not really believe that an artist needs occasionally to use words.” But his charisma was evident. His form master in 1953 recalls: “A legendary figure of fun.”

“I’m just cheeky, and you can get away with cheek, can’t you?” says Hockney. “I mean, if you’re pleasant with it.”

His siblings left school at 16 and although his brother John wanted to be an artist, he became an accountant. There was pressure on Hockney to get a job doing commercial art. In My Early Years, he writes about John: “I was obviously more devious and keener on art than he was.”

Looking back, Hockney says he “talked my way into” going to art school. “Once I got my foot in the door that was it. One local man said, ‘Oh those people at the art school, they don’t do much work.’ And I said, ‘Oh, I’ll work there!’ And I did. I worked from nine in the morning until nine at night, every day. You drew.”

His father, Kenneth, was a pacifist, dandy, antismoking, a public-spirited letter-writer who wrote, among others, to Stalin (an instinct Hockney has inherited, with his letters to The Guardian defending smoking and various fulminations against the “nanny state”). He was “quite an eccentric. I stopped being embarrassed by him when I was 10.”

As Hockney stands for photographs, I ask about his father’s penchant for wearing a watch on each wrist. How would he know which was accurate? “I know,” agrees Hockney, with an enthusiastic peal of laughter. “That’s what I used to ask!”

As to his parents’ opinions on his art, he says, “Their opinion didn’t matter too much. I mean, my mother always liked them. Mothers always like a son’s work, don’t they?”

His contrarianism was evident at the Royal College of Art, where he went in 1959. He once bought a giant canvas to hog space in the studio. “I thought, well, I can get a bit more space with this big canvas. And I did. I painted ‘A Grand Procession of Dignitaries in the Semi-Egyptian Style’ on it.

“It was cheeky. But they said, ‘Well, it’s cheeky, but you’ve got away with it.’ I got away with it. I said, ‘Well of course I’ll get away with it.’”

It was at the RCA that Hockney also started making visibly homosexual art, such as “We Two Boys Together Clinging” (1961). Later, in 1966, the Cavafy etchings openly depicted homosexual love. Lord Browne, the former BP chief executive, who only came out in 2007, regarded him as an inspirational figure. “As a gay person, Hockney being himself so early in the 1960s was remarkable. I looked at him and wanted to be like that.” Browne admits he once owned a rare set of the Cavafy prints in the 1980s but sold them. “I wasn’t out and it was very gay. It was a very silly thing to do.”

Marco Livingstone, who met Hockney in the 1970s and who curated the Hockney show at the Royal Academy in 2012, says: “Hockney’s work spoke to me, as I was coming to terms with being gay. He really changed my life and how I see art.”

Hockney, however, is reluctant to be seen as a symbol of anything, and seems almost insouciant about his influence. He doesn’t see himself as remarkable for being openly gay in the early 1960s, when it was still illegal. “No, because I lived in bohemia and I thought I would always live in bohemia. And bohemia was separate from suburbia and the rest was suburban and stuff.

“At the RCA, Quentin Crisp was a model and I got to know him a bit. I noticed he was the only model who’d go around looking at the drawings and comment on them. He’d make some funny comments. He was one of the first homosexuals I met, who was just gay, accepted what he was and he lived in a bohemian way. That’s what I did and I never thought much of it.”

Hockney may have enjoyed celebrity in London but it wasn’t enough to keep him. He was drawn to LA as his idealised version of America. “I was brought up in Bradford and Hollywood – because Hollywood was the cinema,” he told his biographer Christopher Simon Sykes. He was also in search of sun, sex and space. “I’d say one of the reasons I came here was sex. I knew all these Physique Pictorial [magazine] photographers were based here. I first came in 1964 and it was sexy, it was.”

Above a large pink bucket of paintbrushes in his studio, I notice a calendar of naked rugby stars on the wall. I point it out as Hockney is being photographed. “They’re nice bums,” he bellows, cheerfully from across the room. “I like bums.”

…

After going back and forth for more than a decade, he moved to Los Angeles in 1978, coming back each year to spend Christmas with his mother in Bridlington. But in 2004 he settled more permanently in Yorkshire. One of the results was “Bigger Trees Near Warter”, at 40ft x 15ft, one of the largest ever landscape paintings. It was shown at the Royal Academy summer exhibition in 2007. In a repeat of his RCA cheek, he asked the curators: “Can I have this whole wall for one painting? They didn’t say, ‘How are you going to do it?’ That’s what I thought they’d say. They said, ‘Will it be for sale?’ I said, ‘I don’t know but if you put it up, you’ll get more visitors.’ They did get more visitors and I gave the painting to the Tate. I didn’t sell it at all.”

Were you shocked they asked you about the sale?

“I thought that was absolutely tacky. But when I was putting up the picture, I felt the bad vibes in the back of my neck from the other members. I told Edith [the show’s curator, Edith Devaney] that. I said, ‘Oh I knew it.’ And they didn’t want me to do one the next year. No, no.”

Bad vibes from whom?

“From the Royal Academicians. I mean, they’re all right. They’ll say, ‘Hi David, how are you?’ and then ‘… that fucking Hockney is taking over the whole wall.’ I mean, any organisation is going to be like that. I don’t go to the meetings. I was made a member against my own wishes. Somebody else did it. And I just thought well, OK, I don’t show there that much.”

Despite this tussle, his painting prompted the RA to ask soon afterwards if he would put on a vast exhibition of landscapes. “And I thought, wow, that’s something else. I mean this is big … and then said yes, I’ll do it.” He insisted on doing it in 2012, “because I needed three more springs”.

It also gave him time to experiment with his iPad. He was one of the first people to get an iPad, and it is a medium he has made his own – Hockney draws what is close at hand: his cap, flowers. Frustrated at the number of plugs he needed in Germany, he even sketched his iPad plug with a wry caption: “Will Europe ever unite?” He also embraced filming the landscape, using banks of video cameras set up on the hood of his Land Rover. Marco Livingstone recalls the visceral thrill of visiting Hockney then. “There was this manic productivity – it was a very innovative, prolific time. In eight years he did a lifetime’s work. He reinvented himself as a landscape painter.”

“David has always been an artist who responds to change and stimulus,” Nick Serota told me. “There are artists who have a blossoming at the end of their careers, like Matisse, or 20th-century pioneers like Picasso, who constantly renewed himself.”

“It’s always what you’re doing next,” Hockney agrees. “I mean, I’m a lively artist still so I’m always interested in now, in what you’re doing now, and the past is something…” he wafts his hands poetically in the air. “That’s me anyway, yes. That’s what Picasso was interested in – what he was doing now. You can tell – it shows, doesn’t it? There is a liveliness.”

He never met Picasso. If he had, what would he have asked him?

“I’d have been like a little tiny person. I don’t know, he’s a gigantic artist, gigantic. I would have been very, very humble, I suppose.”

For all this humility, Hockney nevertheless rented the largest artist’s studio ever – a 10,000 square foot factory in Bridlington, big enough to make a full-size replica of the RA space. He is very proud of the show. “I thought it was great, actually, even if others didn’t …” (John Kasmin, his first art dealer, is one such critic of his recent work.)

The show attracted more than 600,000 visitors, double the expectations. After London, it moved to Bilbao and Cologne. “It was seen by 1.2m people. Well I think that’s amazing, considering I’m not Van Gogh or Monet, and they were recent paintings; that’s quite something I think. Yes, that means there’s an audience for them, isn’t there?”

The longest pause of the interview comes when I ask him what could be bigger than that. He starts answering; laughs nervously; stops; leans back in his chair; hesitates. “The show was a big statement about painting, it was. I’m not sure I will do anything like that again, that big. But I’m glad I did them.”

I tell him the paintings made me love trees. Indeed, for Hockney, trees had become friends. “Loads of people have told me that they never noticed trees, and they now start looking; see how beautiful they are in winter and the summer.”

He has an impulse to share his joy of small things.

“Yes. Yes. Yes. You paint to show things, to show what I think of them. That’s how people see the world,” he says. “I can find excitement in the rain on a pool in Bridlington. Somebody else couldn’t. But I can, and that’s the excitement. I mean, yes. Every day, I get it. I’m alive. I feel alive.”

Are you astonished that lots of people don’t feel alive?

“Yes, I am, actually. I am a bit astonished. Yes. They just get the wrong end of it, don’t they?”

…

Although some of Hockney’s paintings have sold for more than £5m, he is not keen on courting modern art collectors. “I don’t know many, actually. It’s a bit mad, isn’t it, the art world, really? I just go on doing the work … I’ve no idea why people buy pictures. I understand living with pictures, but just having pictures in a warehouse doesn’t mean much to me.”

Even as a student he was able to sustain himself by selling art. “I’ve felt rather rich for years and years, meaning I’ve got enough money to do what I want and that’s enough. I think all artists are rich really. If they’re doing what they want to in life, they’re rich.”

His works are dispersed all over the world but he possessively thinks of them as “all mine!” Only one, to his knowledge, has been stolen: a painting of textile designer Celia Birtwell, which disappeared during a party at his studio in the 1980s. “I do miss it because it was mine, and it was Celia.”

He doesn’t want all his work to end up in private collections. It is important that it be viewable by the public.

“I keep more than I sell, actually. Because I’m going to give it away, I mean I’ll give it to the Tate or to the [Los Angeles] County Museum. I’ve kept a lot. I don’t want to sell them.”

Last weekend, he painted a portrait of the art dealer Larry Gagosian for the first time. “He came up here, and I said, well I’ll paint you. I’ve known him a long time, and I’ve looked at him. And I thought, well. And he said OK, and I said OK.

“He’s always wanting me to show [with him] but … Larry, he’d sell everything; I don’t want to sell everything, I don’t.”

He laughs conspiratorially when I ask whether he would give the portrait to Gagosian (an obvious wind-up, given his reputation as the world’s most successful art dealer). “No, not to him,” Hockney says. “I’m not giving it to him. No … he’ll have to buy it!”

With his legacy on my mind, I am intrigued to see on his studio wall a reproduction of the unfinished painting of Wayne Sleep and George Lawson, the one he’d abandoned in the 1970s. It is displayed next to a copy of “Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy” (the original at the Tate was voted by the public into the “Top 10 Greatest Paintings in Britain”), which he painted immediately before it.

Did he regret not finishing it?

“Well I don’t know, I just felt it was going in an odd direction and I abandoned it and went to Paris … And then I started painting in a different way. But looking back on it now, when I got it out, I thought, well it’s fine actually, there’s a lot there, it looks good.”

The painting had been rolled up for 20 years. “I had it brought over here and pinned on a wall down [in his studio] on Santa Monica Boulevard for a bit. And now we’ve had it stretched and repaired. I’m thinking of giving it to the Tate … I mean, they could hang them together [the two paintings] for a while; I think they’d look good on that wall.”

…

The San Francisco exhibition opens in three weeks’ time. He was still selecting pieces. One room will show his charcoal drawings, “The Arrival of Spring in 2013” – a project he nearly abandoned. “I was drawing it before it had happened. I realised I was being impatient and you have to wait until there’s something else there for you to see. And there is. There’s always something being added as you go along. I’m very proud of them, actually, very proud. I think it’s one of my great works, this, the 25 drawings.”

I am interested in how he picks a particular spot, which so many of us would barely notice. He takes me through the grid. “The other one was chosen because I knew there would be a hawthorn there. That top one took three days to draw. Three days! The right-hand side bit took four or five hours to draw – that bit above the road. It took a long time until the last ones. They are drawn quicker because you’ve got the sun out. You want the sun and the sun might go in, it’s not California, the sun might not last, but I knew for the very last one the sun was going to come out. I was there at 6.30 in the morning waiting for it, when the shadows would come across the road.”

He will also include more video pieces and 14 of the new portrait paintings, including the one of Gagosian. He prefers drawing people he knows, interrogating their faces like a landscape. “If you know them well, you’ve got different memories of them. I mean, that’s what we’ve all got. We all see with memory, don’t we?

“I made about 25 portrait drawings that took a day or two [each] to do. Now I’m doing portrait paintings. I mean, they say in the art world, you can’t do landscape or portraits now. Well, that wall tells me you can. The idea you couldn’t do landscape implies we’re bored of nature. We can’t be bored of nature. It’s not possible, really. It’s from nature that new things come, isn’t it?”

I wondered if looking at the wall made him miss Bridlington.

“A bit. I’ll be back, I suppose. I’ve missed here. I’m all right here for a while … I’m very conscious I live the same way here. I go down the hill and this is Hollywood, but I don’t go down that often.”

Looking at the charcoal drawings, I find it hard to believe he won’t be back to see another Yorkshire spring.

“I don’t know. I might, because the spring is the loveliest time there. The spring takes a month to happen. In North America it takes a week and then it’s the summer. It’s a lovely, lovely time of year, it is, for nature.”

Many art critics, though, prefer his early work to his landscapes. Does he mind that?

“My work will stop when I fall over,” he says, reaching for another cigarette. “And then you’ll look at it, and they will see something else. Well, they’ll see then, more what he was about, actually, I think.”

And what does he think his work is about?

“Space. Images. I’m deeply interested in images. I’m not sure what it’s about, totally. But I think at the end, when you put it together, I mean it does have a lot of variety, my work, a lot more than a lot of other artists.

“I mean, most artists get forgotten, they do. Most art gets forgotten. It might be. I don’t know. I won’t care, really. I’ll be gone to another adventure. Another adventure! Yes.”

He lifts a thumb to indicate the space behind him, as if wryly amused by the course his life has taken. “This one was a weird, way mysterious one. Isn’t this mysterious? Why shouldn’t there be another?”

——————————————-

Caroline Daniel is the editor of FT Weekend. ‘David Hockney: A Bigger Exhibition’ is at the de Young Museum, Golden Gate Park, San Francisco, October 26-January 20 2014. A book of the same title, with texts by Richard Benefield, David Hockney, Sarah Howgate and Lawrence Weschler, is published by DelMonico Books – Prestel in association with the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco on October 21 (£45). To comment, email magazineletters@ft.com

Comments