Joy Simmons: ‘Supporting young artists is more important than collecting a big name’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Most art collectors start with a rather scattergun approach to buying, acquiring in a random fashion before gradually homing in on the focus they want to give their collection. Not the Los Angeles-based collector and radiologist, Joy Simmons. From the get-go she knew she wanted to collect work that reflected her own heritage as an African American. “When I was in college, I visited my aunt’s home in New York. She had sculptures by Melvin Edwards, paintings by Howardena Pindell and Jack Whitten: the heavy hitters. It was eye-opening for me to see work by black people that reflected my reality; at that point I started to think about how such works could impact on my own space,” she says.

That was over 40 years ago now, and Simmons has continued on that path ever since, gradually building up a major collection of work by black artists. And on the few occasions when she has acquired a work by a white artist, it reflected the black experience: for instance, a lithograph of Norman Rockwell’s “The Problem we all Live With” (1963-64), showing six-year-old Ruby Bridges being escorted to school by FBI agents. “I had to talk my husband into buying it,” laughs Simmons. She also has a vivid and joyous screen print of Andy Warhol’s “Queen Ntombi Twala of Swaziland” (1984). But the overwhelming majority of her collection is by African American creators.

Simmons is talking to me via Zoom in her Los Angeles home, wearing a bright orange dress, with large hoop earrings dangling to her shoulders. She is exuberant and enthusiastic, punctuating her comments with laughter, sometimes pausing dramatically to find exactly the right answer to a question. She comes from a middle-class family and expectations were high that she, like her parents, should do well — in fact, she attended Stanford before going on to study medicine at UCLA. “I was the only black girl in my class — we started with two black women and four black men out of 150 students but the other woman dropped out so there was just me,” she says, admitting that “there were challenges, which I wasn’t expecting in med school, but I dealt with them . . .

“I was always a very visual person, which is why I chose radiology!” she continues. “I wasn’t listening to hearts, touching skin, cutting people; I was looking at images all day.” She emphasises the “all day”.

Back when she started collecting more than 40 years ago, works by African American artists had not reached the stratospheric price levels they now command. As a result, Simmons was able to acquire works by artists such as David Hammons, Kerry James Marshall, Julie Mehretu, Mark Bradford or Mickalene Thomas. “When I bought them, the market was in a very different place,” she explains.

I ask her what she thinks of the current frenzy for these artists, and the prices they fetch. She thinks for a moment. “There is so much money out there today. The validation of people appreciating the black story resonates with so many. But people interested in acquiring trophies are changing the market. I am not in that league,” she says, finally.

“I tell young collectors to pay attention and buy what resonates with them. When I bought works by Hammons or Bradford, I didn’t know what they would go on to be — I just bought what I loved.”

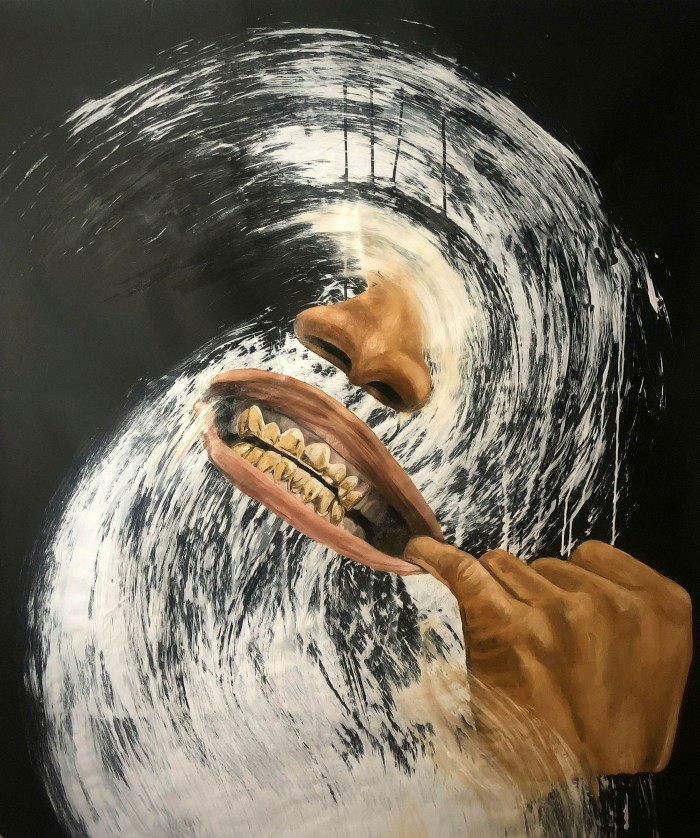

More recently her focus has been on spotting and supporting young artists. “That’s the fun part of collecting!” she exclaims. “Meeting artists, helping them along their journey. I am not interested in collecting artists that are now deemed ‘important’ because by that time they are definitely out of my radiologist’s budget. Giving young artists that validation, supporting them at a crucial stage, that is more important than collecting a big name.” She cites the young artist Khari Turner, whose swirling image, “Angel of Thugz Mansion” (2020), she bought when he was still at college. “I saw a show by him in New York last week — it is thrilling to see how he has progressed since then, and I love that I have contributed to the arc of his career.”

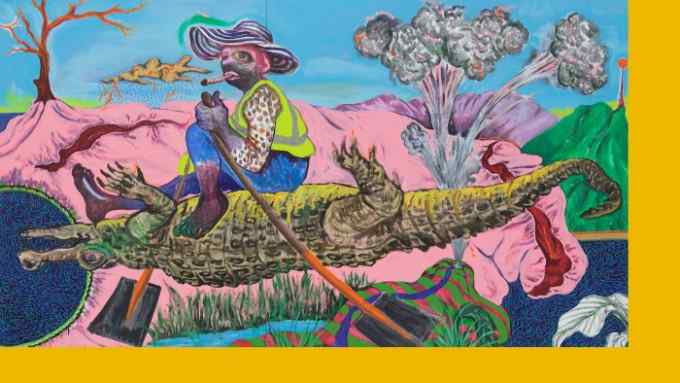

Her house is, she admits, “crammed — I never sell!” Indeed, as she shows me around via her laptop, I am able to see for myself — not many surfaces are unadorned. Over the staircase hangs a work by Felandus Thames, “Existential Crisis” (2020), consisting of hairbrushes spelling out B.B. King’s lyrics “Nobody loves me but my mother, and she could be jiving too”. A Wangari Mathenge, “The Ascendants” (2019), showing two figures seated, hangs over the sofa. Close by is a portrait of three black girls (“me and my two daughters”, Simmons laughs) by Deborah Roberts, entitled “An Act of Power” (2018); there is a delicate portrait in pencil of her mother by Kenturah Davis. Even the bathroom has a 2019 site-specific installation of images taken from Jet and Ebony magazines by Genevieve Gaignard, incorporating “Phenomenal Woman, That’s Me!” (2017). As she says of living with her collection: “I like sitting among my friends.”

She is now mainly retired from medicine, but certainly not letting up, although she says she has “definitely become more selective [in her buying].” She is a commissioner at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington and Trustee Emeritus at Stanford University and a member of its arts council, as well as advising other arts initiatives. “I am selective about these boards as well — I am not able to be a big donor, my activism and support is different.”

“I often host groups of Stanford people,” she continues. “Some white students from privileged backgrounds have never been to an upper-middle-class black home. It is important for young people know that we are ‘just like you’.”

One of her two daughters, Naima Keith, followed in Simmons’ footsteps, studying at Goldsmiths in London; she is now vice president of education and public programmes at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Did her children love art from an early age? “In a word, no!” says Simmons, laughing. “When they were children they hated going to museums. They knew when I said we were going on a ‘new adventure’ — it was a code word for a gallery, studio visit, museum. And now I have grandkids, we still joke about that, my ‘new adventures’!”

Comments