Opportunities and risks for investors in central and east Europe

Simply sign up to the Currencies myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Central and eastern Europe has attracted some negative headlines in recent years. Poland and Hungary have shifted to a more “illiberal” democracy, foreshadowing the rise of nationalist populism symbolised by the UK’s vote to leave the EU and Donald Trump’s election as US president. Clashes between Brussels and some countries in the region over how to handle Middle Eastern refugees is a prime example of this change.

Yet even if investors now have to tread more carefully in certain sectors and countries, the region’s underlying attractions remain broadly undimmed. The former communist countries that have joined the EU since 2004 offer superior growth to western Europe and many other emerging markets, combined with the benefits and protections of EU membership.

As Deloitte noted in a report last December, “core” countries in the region such as Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Romania are “growing faster than any region in the world with the exception of Asia Pacific”.

For investors with higher risk appetite, countries beyond that core and outside the EU, including Russia, Ukraine and south-east Europe, are starting to recover from recession or weaker growth in recent years.

In the most developed countries of central and eastern Europe (CEE), wage levels have increased sharply since the fall of communism and EU accession. But with pay rates also rising in other emerging markets, central Europe’s wage costs are still competitive — and workforces are well-educated and skilled. It combines those advantages with a location close to the heart of the EU single market, improving infrastructure, and healthily growing economies and consumer spending.

Indeed, consumer demand — for years rather weak in CEE — is an increasingly important driver of growth. Unemployment is falling to post-communist lows, while low inflation and falling energy prices have boosted real incomes.

Moreover, for every single percentage point of growth in the eurozone, the region’s most important market, CEE countries are reckoned to grow by up to 1.5 percentage points. Juraj Kotian, head of CEE macro research at Austria’s Erste Group, forecasts growth in the five biggest CEE markets plus Croatia, Slovenia and Serbia will accelerate to 3.3 per cent this year from 3 per cent last year.

Political risk has, however, re-emerged as Hungary’s Fidesz government, followed by the Law and Justice government in Poland, have embraced a form of economic nationalism.

Arguing that they surrendered too much economic sovereignty when privatised companies were sold to foreigners in the 1990s, both have sought to return some control to national hands. Poland’s Law and Justice government has aped steps by Hungary’s prime minister Viktor Orban to squeeze some foreign-dominated sectors.

“We have seen policies [in Hungary and Poland] which could be viewed as nationalist in the financial, telecommunications and energy sectors,” says Andrius Tursa, an analyst at Teneo Intelligence, a political risk consultancy. “Both countries have also attempted to impose restrictions on large — generally foreign-owned — retail chains.”

Poland’s banking tax was less severe than Hungary’s and its supermarket tax has been suspended pending an EU review. But despite pressure to reduce coal consumption to mitigate climate change, Warsaw took steps last year to protect its coal sector, a huge employer, by imposing regulations on its thriving wind energy industry that could force some projects out of business.

Sir Suma Chakrabarti, president of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, says Poland was long one of the bank’s success stories, but now “we worry about some of the policy” in areas such as banking and renewable energy. “Those are business areas where . . . when we talk to investors they say we’re not really as confident as we used to be,” he says.

Yet in other sectors, including the auto industry and electronics, Warsaw and Budapest are continuing to welcome outside investment. In a sign of confidence, Daimler, the German car manufacturer, last year announced planned investments totalling €1.6bn to expand an existing manufacturing plant in Kecskemet, 50 miles from Budapest, and build a second one alongside it.

For now, moreover, while nationalist populism has expanded outside central Europe, it seems unlikely to spread much further within the so-called Visegrad Four, which includes Poland, Hungary, Czech Republic and Slovakia, or beyond.

“While V4 leaders share some populist and social-conservative tendencies, the Czech Republic and Slovakia are unlikely to make a broader turn towards ‘illiberal democracy’ in the near-to-medium term,” says Mr Tursa. Slovakia’s next elections are not until 2020, he says, while the likely winners of Czech elections late this year have so far stood for business-friendly policies.

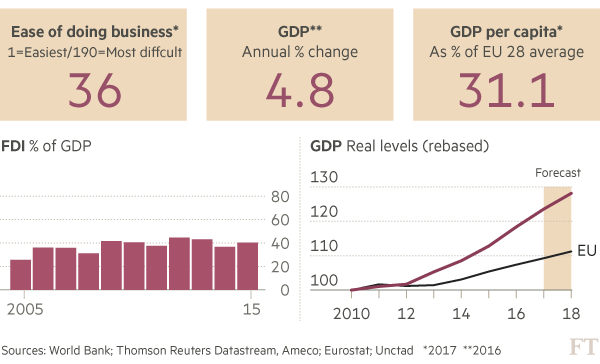

See below for a dashboard outlining the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and risks in the five big CEE markets

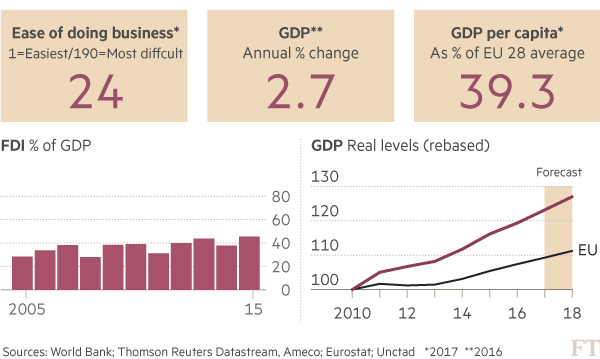

Poland

Strengths

The largest domestic market in CEE and one of Europe’s fastest growing. Economic growth continued strongly right through the global financial crisis and the eurozone crisis. Labour costs remain relatively low compared to western European markets, with education standards rising in recent years.

Weaknesses

Big disparities in prosperity persist between regions. Red tape can complicate doing business. Infrastructure, including rail, remains under-developed compared with the rest of the EU, but investment is improving it fast.

Opportunities

Poland is the biggest beneficiary of EU structural funds, providing opportunities for investors to invest in projects alongside European money. Low unemployment is boosting consumer confidence and spending.

Risks

The Law and Justice government is pursuing nationalist economic policies, though it has stepped back from some of the more potentially damaging measures, including forcing banks to convert foreign-currency mortgages back into the local currency as Hungary did. Reforms seen as undermining liberal democracy have stoked turbulence with the EU and occasional popular protests.

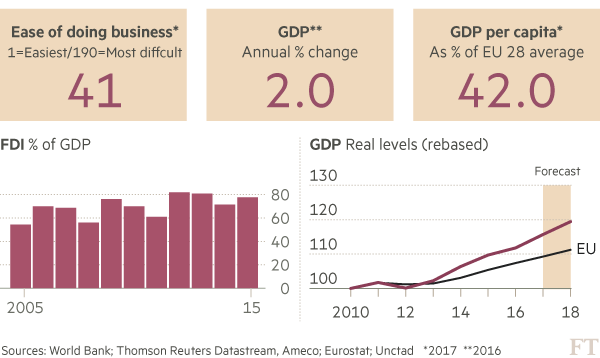

Hungary

Strengths

Hungary benefits from a well-developed economy and a high standard of education. Rail links are good from a country at the heart of the central and eastern European region.

Weaknesses

Recovery from the global financial crisis — when Hungary was one of the first countries hit — initially sputtered under the Fidesz government’s “unorthodox” economic policies. Though growth recovered strongly by 2014, it has eased since and economic policy remains less predictable than some neighbours.

Opportunities

A large auto industry and top-ranked electronics manufacturing sector, according to Deloitte, offer attractions for investors in those and related sectors. Outsourcing is another strength.

Risks

The Fidesz government has made life less comfortable for foreign investors in some sectors and clashed with the EU over controversial political reforms and its immigration policies. Pressure on non-governmental organisations and Budapest’s Central European University have stoked concerns again in recent months.

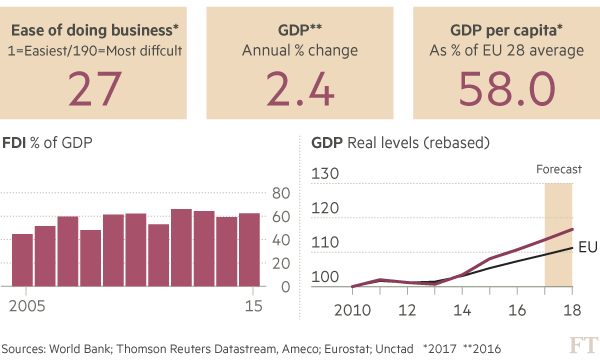

Czech Republic

Strengths

Czech Republic is one of the region’s wealthiest and best-developed economies, well on the way to catching up to the EU average in GDP per capita. It also has the best infrastructure. Though wage costs are higher than neighbours, the workforce is skilled and the business climate remains attractive.

Weaknesses

A smaller domestic market compared to countries such as Poland makes it more sensitive to fluctuating eurozone demand.

Opportunities

Large and well-established auto manufacturing and electronics sectors provide a deep pool of engineering know-how, says Deloitte. KPMG notes that nanotechnology industries, along with other high-end technologies, have developed rapidly and represent a good opportunity for investors.

Risks

April’s removal of the cap on the Czech koruna could lead to currency appreciation, but exchange rate movements have been reasonably contained. Elections later this year could see a shake-up of the ruling coalition with the Ano party of billionaire Andrej Babis, the finance minister, emerging on top. The “centrist-populist” Mr Babis, however, is not in the same mould as the region’s more nationalist leaders.

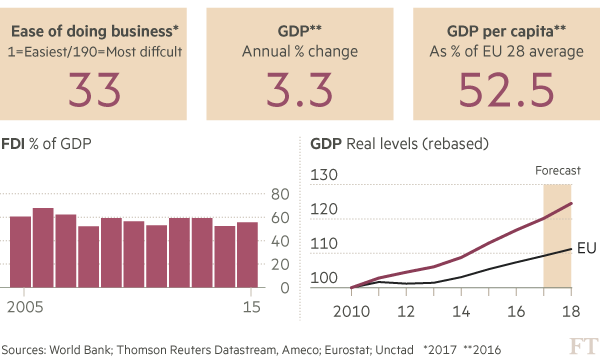

Slovakia

Strengths

Boosted by reforms in the past decade, the country once dubbed the “Tatra Tiger” has seen rapid development to become one of CEE’s wealthiest states. Membership of the euro, since 2009, reduces currency risks for eurozone investors. KPMG notes it is the regional leader in labour productivity.

Weaknesses

Joblessness this year dropped below 9 per cent to its lowest level since 1990. Yet it remains high by current regional standards, and wages are not as competitive as they once were.

Opportunities

The highly successful automotive sector — set to be strengthened by a Jaguar Land Rover plant from 2018 — provides opportunities across the supply chain, with other engineering, electronics and IT sectors also strong. The capital, Bratislava, is just an hour by car or train from Vienna.

Risks

The three-party coalition government in place since last year may prove less stable than some of its predecessors, though the risk of early elections before the next scheduled poll in 2020 seems small.

Romania

Strengths

Poorer and less developed than the other four countries here, Romania joined the EU three years later, in 2007. But that makes its labour even more competitive. With consistently fast growth in the past three years and a strategic location at the crossroads of commercial routes connecting the EU, the Balkans and Asia, Deloitte calls it the “new sexy” destination.

Weaknesses

Governance is weaker and the judiciary and bureaucracy are less well developed than in other CEE locations and western Europe, with the fight against corruption not as advanced.

Opportunities

There is scope for “catch-up” growth in infrastructure and construction, and for modernising an agriculture sector with a high percentage of quality arable land. Access to Black Sea ports is another plus.

Risks

Though President Klaus Iohannis has made fighting corruption a key goal, the socialist government elected in December provoked the biggest protests since 1989 by proposing to decriminalise some forms of lower-level corruption. It backed down — but raised questions over predictability of policy.

Additional research by Sebastien Ash

Sources: Deloitte, KPMG, PwC, World Bank

Comments