Apple’s EU tax dispute explained

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Ireland will on Tuesday be ordered to claw back billions of euros from Apple, triggering one of the world’s biggest tax disputes and a political showdown between Europe and the US.

Based on an obscure 1991 Irish tax ruling issued for Apple, then a struggling computer maker, the Brussels competition decision has the potential to transform how corporate tax avoidance is policed in Europe.

The order to recoup back-taxes is expected to potentially be big enough to ricochet into the US election campaign, overshadow Apple’s latest product launch next week, and set in train a landmark legal battle.

Ireland and Apple strongly deny any wrongdoing and see the decision as an egregious example of over-reach by the EU’s executive arm that will not stand up to scrutiny in court.

What is the dispute over?

At the heart of the matter are tax arrangements that helped Apple pay an ultra-low rate of just 4 per cent on nearly $200bn of foreign profits it has earned over the past 10 years.

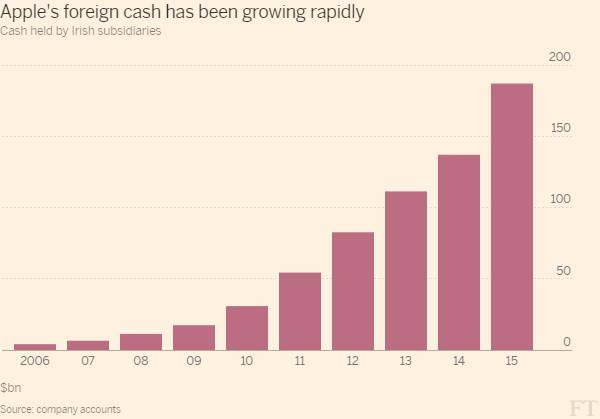

Apple’s lightly-taxed foreign cash mountain is the biggest of any US multinational.

The $187bn it held outside the US in 2015 accounts for a big share of the $1.2tn that US multinationals have parked offshore, in the hope that US tax reform will eventually cut the cost of repatriating the profits.

So far, Apple’s foreign profits have been lightly taxed.

What is the commission’s complaint? Why was Apple’s Irish arm so important?

About 90 per cent of Apple’s foreign profits are earned by Irish subsidiaries, which are highly profitable because they hold rights to Apple’s intellectual property.

But these Irish entities paid little tax because they were not tax resident anywhere — a structure that exploited differences between the US and Irish definitions of residence.

The European Commission is targeting the arrangement on the grounds that it gave Apple an undue tax advantage that distorted competition. It alleges this amounted to illegal state aid, a breach of the EU’s unique restrictions on state support to companies.

While it builds on similar commission tax decisions recently served against deals for Starbucks in the Netherlands and Fiat in Luxembourg, the Apple case is by far the biggest and most significant.

What is Apple’s position on the investigation?

EU investigators have examined how Apple paid a tax rate of less than 1 per cent on European sales in some years. But the company insists it pays every cent of tax owed in every jurisdiction.

Tim Cook, Apple’s chief executive, told the Washington Post in the past month that the tax structure deployed in Ireland was applicable to all companies and that it was not unique to Apple. In other words, Apple gained no special treatment in Ireland and therefore enjoyed no selective state aid.

With some passion, he personally pressed the company’s case with Margrethe Vestager, EU competition commissioner, in January. He also says the company is the biggest taxpayer in the US. “And so we’re not a tax dodger. We pay our share and then some.”

How will Ireland respond?

Ireland’s position is that any arrangement which gave tax advantages to Apple that were not available to other companies would have been illegal in Irish law. The country’s corporate tax regime has proved controversial with France and Germany.

Still, the Dublin authorities have taken a succession of steps in recent years to unwind the most contentious elements of the regime. Such moves include the elimination of the “stateless” tax structure deployed by Apple to minimise its tax rate in Ireland. Like Apple, Ireland is set to appeal the ruling in the European courts.

Why is the US so irked by the case?

This is more than a struggle between Brussels, Apple and Ireland. At the root of political concern in Washington is anxiety that profits are held abroad by US companies. In theory at least, forcing Apple to pay back taxes to Ireland would reduce the pool of money that might ultimately be taxed in the US.

Last week the US Treasury accused the commission of behaving like a “supranational tax authority” that threatened international tax reform agreements through the inquiries. This was on top of a direct plea from Jack Lew, Treasury secretary, to Jean-Claude Juncker, commission president, to reconsider the investigation. Earlier this year the Senate finance committee urged Mr Lew to consider a double tax rate on European companies if Apple was ordered to pay back taxes to Dublin.

What are the wider implications?

Appeals against the ruling will take years to resolve. But ultimately if the commission prevails in court, the decision will reset the balance of power on tax policy in Europe.

While governments will still be able to set their own tax rates, the commission will have established itself as a watchful referee of how national rules are implemented.

And the example of Apple — and its multibillion-euro bill in back taxes — will be a warning to big global companies to put their affairs in order, at least in Europe.

Success on appeal for Apple and Ireland might relieve some of that pressure, and give national governments more leeway.

But until then it threatens to upset US-EU relations, potentially further hampering already difficult talks on a trade deal. And for the moment, the commission’s ruling will stand as a severe blow to exotic avoidance strategies.

Comments