Carmakers drive across central eastern Europe’s frontiers

Simply sign up to the European companies myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Jaguar Land Rover’s decision to consider Slovakia as a base for building luxury sport utility vehicles and four-wheel-drive cars may have raised eyebrows on shop floors in the UK’s West Midlands. But, if anything, what is surprising is that JLR was so late to the party. After all, Porsche and Audi have been building top-of-the-range cars in eastern Europe for years.

Central and eastern Europe’s car industry, once associated with building and selling unreliable clunkers, has become an industrial byword for the region’s wider economic rise. It has replaced the inefficiency and low standards of Soviet-era manufacturing with some of the most modern and productive plants in Europe.

Production was initially propped up by demand for local marques such as the Czech Republic’s Skoda. It began to rise with the arrival of non-European brands, including South Korea’s Kia and Hyundai, which were seeking a cheaper EU location than countries such as Germany.

Established western brands such as Fiat of Italy and France’s Peugeot Citroën followed suit, looking to lower their costs while maintaining quality standards and access to the single European market. In the decade to 2010, European brands opened a third of all their new automotive factories in central and eastern European countries, a higher concentration than anywhere else. In the past 15 years, it has been the only large region apart from China to increase its market share of car production. Additionally, since the financial crisis in 2008, Slovakia, the Czech Republic and Romania are the only countries in the EU, apart from the UK, to have seen car production rise.

This growth has been in large part fuelled by the shift from low to mid-value production and by parts of the supply chain moving from western Europe, according to Karel Stransky, a director at Colliers International, a property management firm. He adds: “This has been underpinned by factors such as low labour costs, government support and infrastructure improvements across the region.”

It is the attitude of foreign investors that has changed dramatically since the region established itself as an important car production hub. Before, companies would carefully weigh up each country’s national attributes before deciding where to build a factory. Today, they consider the region as one joined-up sourcing, manufacturing and logistics market.

“Now investors that come to central and eastern Europe behave very differently from five or seven years ago,” says Andrzej Posniak, partner at the Poland offices of CMS Cameron McKenna, a law firm. “From a business perspective, what matters now is hugely different. People do not think about national ideas. They invest in the region.”

That approach was most obvious in JLR’s strategy for selecting the location of its factory. The Indian-owned group was confident that Poland, Slovakia, the Czech Republic or Hungary could deliver the resources and benefits it wanted.

“Negotiations over location were more about the financial and related benefits, not necessarily the physical attributes of each potential site, though of course they were considered,” says a person involved in the JLR talks who asked not to be named because the investment is not yet finalised. “The quality standards, supplier networks and employees are all much the same around the region, so they were less concerned about those things.”

Jostling between the region’s countries to land big automotive deals is likely to become only more competitive as governments look to larger incentives and financial assistance packages, including tax exemptions and access to economic zones, where certain levies can be waived.

“The important change from the producers’ perspective is the extension of economic zones, which is under consideration right now,” says Piotr Michalczyk, a partner and leader of automotive services at the Poland offices of PwC, the professional services firm. Referring to Warsaw’s own offering, he adds: “A new tax relief on technology may also have a significant impact. It will enable, more than currently, additional reductions of part of eligible costs related to research and development. When that happens, it will be great news, especially for small and medium-sized enterprises.”

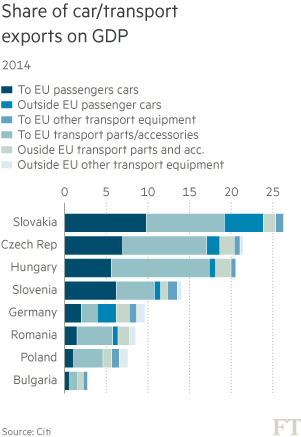

Such steps are crucial. While investment announcements concerning big car factories such as JLR’s grab headlines, much of the region’s automotive success stems from the legions of local manufacturers and producers of accessories and parts that have built a formidable supply network across the region.

This network was initially fostered by German automotive suppliers looking for lower-cost outsourcing options. Nowadays it not only employs vastly more people than full car manufacturing, but also accounts for roughly 40 per cent of the region’s total automotive-related exports.

Volkswagen sources billions of euros worth of cars, engines and parts from factories across the region. The importance of CEE manufacturers and suppliers to the global car industry was starkly underlined by the eruption of the VW diesel engine scandal this summer.

Fast-emerging countries to the east are snapping at the heels of the region’s traditional automotive producers of Poland, Slovakia, Hungary and the Czech Republic — the so-called Visegrad Four — even as they look to attract manufacturers away from developed western markets.

One example is Romania, which joined the EU in 2007, three years after the Visegrad Four. It has grown rapidly into a big rival. Its local low-cost Dacia brand, owned by the Renault-Nissan Group, has become a runaway success among cash-strapped drivers in western Europe, driving up demand for parts and attracting international suppliers to set up factories in the country.

Romania’s automotive exports this year should be roughly in line with the value of Poland’s in 2012, and are growing at a faster rate.

In contrast, investment has not only dried ups but is retreating in Russia, a market described by carmaking executives as the world’s most frustrating.

Once talked of as the most promising market in Europe, Russia’s latest slowdown is a result of the collapse of oil prices, and of western sanctions imposed after the Russian invasion of Crimea.

Both events sent the rouble tumbling and inflation soaring, jacking up the prices of imported cars, cutting Russian consumers’ spending power and making it costly to run foreign factories that are reliant on overseas parts. Since 2013, domestic car sales have fallen by more than 40 per cent.

That was a body blow to carmakers that had invested heavily in the country over the past decade and had been convinced that the market would finally live up to its expectations.

This year General Motors swallowed a $600m write-off and shut its St Petersburg plant. While rivals are still plugging away, and some Chinese carmakers are moving in, it is a far cry from the expectations many had five years ago.

Comments