Travel discoveries and disappointments of 2015

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Martin Fletcher

Discovery: A wild retreat, Scotland

Call me a Puritan, but I hate spending money on excessive luxury, hate being pampered, hate having everything done for me. And while I’m at it, I intensely dislike airports, crowds and regimentation, which is why I was thrilled to rediscover the subtle pleasures of the traditional hair-shirt holiday on Scotland’s west coast last summer.

Nearly 40 years ago two friends from Edinburgh university and I spent an idyllic week studying for our finals at a remote croft, accessible only by water, that one of their families owned on Loch Hourn, a sea loch 100 miles north of Glasgow. This was the reunion, plus wives. Little had changed. First the 20-mile drive down a single-track road to reach Kinloch Hourn, a settlement of just a couple of houses at the eastern end of the loch. Then the ferrying of provisions to the boat; the 40-minute voyage to the white stone cottage on a tiny clearing between the mountains and the water; the same initial doubts as we disembarked amid miasmas of midges and rain. The croft still has no electricity, no phone, the most basic of kitchens and just one shared bathroom.

Here enjoyment must be earned. By hiking up hills to admire the majestic views, and to revel in the loneliness of it all. By canoeing to where the seals flop off rocks to inspect you from the water. By plunging into that freezing water so you emerge feeling tingly and virtuous.

It comes from that sudden tug on the line unspooled behind the boat, and the eager anticipation as you haul up lobster pots filled with fish and crabs but never, dammit, a lobster. It lies in those perfectly silent early mornings when it is hard to tell which is real — the sublime scenery or its reflection in the glassy water — and in those magical moments when shafts of sun break through the mist and bathe a muted world in colour.

Above all, it comes from the camaraderie born of shared physical activities, the renewing of old friendships in the most remote and beautiful of surroundings, the joking and bantering and convivial discussions over unhurried dinners as those endless northern summer evenings fade slowly into night.

The Barisdale Estate (barisdale.com) has two remote cottages to rent on the south side of Loch Hourn: the Whitehouse, which sleeps up to 12 from £120 per night, and the Stables, for up to five, from £95 per night. Kinlochhourn Farm (kinlochhourn.com) in Kinloch Hourn has a cottage for up to five, from £150 per night. On the north side of the loch, Grieves Cottage and the Old Post Office sleep six and four respectively, both from £325 per week; arnisdale-estate.co.uk

Disappointment: A tourist crush, Cambodia

Visiting Angkor Wat during the Chinese new year was rash, but we arrived before dawn to find crowds worthy of a Premier League football match queueing for tickets outside Cambodia’s fabled temple complex. The temples themselves were lost amid the hordes. In our eagerness to see those ancient wonders we have destroyed them.

Tim Moore

Discovery: A Bauhaus beauty, Germany

I wobbled into Probstzella one evening last spring, halfway through a stupidly overambitious bike ride down the full length of the old Iron Curtain, from the top of Norway to the Black Sea. Its curious name had leapt off the map and I’d pedalled deep into the sunset to see if its looks matched. They did. Low rays gilded the flanks of pine and Thuringian slate that hemmed Probstzella in and cast a flattering glow over its winding straggle of grimy old homes. Opposite them lay the ghostly bulk of a red-brick railway station — one of the few that had linked East and West Germany in the old days, now surrounded by a derelict sprawl of windowless buildings and weed-fractured concrete. And atop everything, looking down on this entirely unpeopled scene, an extraordinary red eminence sprouting angular pavilions and topped with a Gotham City turret.

The Haus des Volkes was built in 1927 by Bauhaus architect Alfred Arndt for a philanthropist who had chosen to endow this remote slate-mining community with a cathedral-sized community centre. As a GDR border town Probstzella was declared an exclusion zone, and just 20 years after it welcomed its first workers, the Haus des Volkes was shuttered up. In 2008 it reopened as a hotel, though off-season you’d hardly guess it: I rang a phone number stuck to the bolted door and was given a code that accessed the key box alongside. Then I went in and didn’t see a soul until breakfast. All evening I wandered alone down corridors and stairwells lined with shriekingly vibrant modernist murals, peering into the original bowling alley and a trapezium-vaulted, thousand-seat theatre, savouring all five floors of hard lines, smooth curves and lofty, slender windows. The grounds were similarly deserted and no less splendid, strewn with copper-roofed refreshment kiosks, each a sinuous study in brick and glass, like pocket prewar Tube stations. Then, because it was my birthday, I sat down on the leaf-scattered bandstand, opened my rucksack and drank an awful lot of warm beer.

Double rooms at the Haus des Volkes cost from €69; probstzella.de

Disappointment: A bureaucratic trial

No one does the Stare of Towering Bureaucratic Indifference quite like a Russian visa official. And how utterly monstrous the application process: “List your last two places of work, excluding the current one.” “List all countries you have visited in the last 10 years, and the dates of each visit.” I was only in Russia for four days and the visa cost me more than all my hotels did.

Paul Richardson

Discovery: The perfect beach, Portugal

Last summer I spent a long weekend in Portimão. The south coast of the Algarve might have been my travel disappointment of 2015, except that I hadn’t raised my hopes high enough for them to be properly dashed. But from Portimão I turned tail, drove to Cape St Vincent, Portugal’s south-westernmost point, then rounded the corner and came upon a different world. The Algarve’s western seaboard, a rugged strip of rock, sand and scrub running north from the Cape to Odeceixe, may be the best preserved 60km of coastline anywhere in southern Europe.

Even at the start of August, there was an appealing sleepiness about the whitewashed villages strung along the coast road, with their scattering of B&Bs and “surf lodges”. In one such village, Rogil, I turned off the N120 on a whim towards Praia da Carreagem. I parked the car, then stared down in amazement from the steep wooden stairway at a lavish stretch of unspoilt beach backed up by cliffs and greenery. The next few days held more surprises. Bordeira, Amado and Arrifana were beaches for connoisseurs of real beaches, not the warm-bath sandpits of the Mediterranean and their paraphernalia of sunloungers, showers and chill-out music.

And none of them was more flagrantly, fiercely beautiful than Castelejo, a few miles out of Vila do Bispo — a beach to make you feel small and awestruck as you potter among the rock-pools, contemplating the dark grey crags and the thunderous Atlantic rollers (far too rough and bracing for an idle dip). Among the few visitors I detected a certain solidarity: we were all here because we craved primitive wildness in our beaches, not massages and Magnums.

I watched a couple walk hand in hand along the sand, back-lit by the setting sun, naked and unashamed. My heart was in my mouth. If you can be moved by a beach — which you should be able to be — then I surely was. And, just as surely, I’ll be back next summer.

For details of accommodation and travel, see visitalgarve.pt

Disappointment: A mysterious anticlimax, Peru

I was excited about my trip to Machu Picchu. This was, after all, the fabled city that had fallen into oblivion before explorer Hiram Bingham stumbled . . . you know the rest. But as the packed minibus crawled out of a ramshackle settlement seeming to consist entirely of souvenir stalls, I had my first inklings of a let-down. Up at the site, throngs of tourists tramped dutifully among the stones. Machu Picchu seemed a victim of its own enigma. The Incas left no written record of the city; few domestic objects have been found; even the name is a hazarded guess. I peered through the drizzle, wishing there was, I don’t know, more to see. The mystique of Machu Picchu had, like the Snark, softly and suddenly vanished away.

Peter Hughes

Discovery: A conservation success story, Australia

Arkaba is an exclusive little wilderness lodge deep in the uplands of the South Australian outback. Once a sheep station homestead, it crouches beneath the frowning crags of the Flinders Ranges about 280 miles north of Adelaide. Dating from 1851, it is a classic Australian country house, timber-built, single-storey and shaded by wide verandas and a spread of roof that could have been flattened by the Aussie sun. Around it stretches a gnarled landscape of great bluffs of prehistoric rock, boulder-strewn river beds and ranks of massive, thousand-year-old red river gum trees.

There are five guest rooms, one in a cottage in the garden. All they have in common is air conditioning, en-suite bathrooms and designer rusticity. Bedside tables look like hessian woolpacks; merino fleece headboards are stretched between cypress fencing posts, and towel rails are made from sack barrows or guillotine-like wheat-cutters. I dined outdoors at a table from a shearing shed on prawns in pea purée, listening to the squeal of galah cockatoos.

When Wild Bush Luxury, a leading operator of outback billets, bought Arkaba six years ago it came with 64,000 acres of bush and 6,000 sheep. Now the sheep have been extradited and the land they grazed, an area almost the size of Birmingham, is devoted to 10 guests and wildlife conservation.

The station is also ridding itself of goats and rabbits, which destroy vegetation, and predators such as foxes and feral cats. “The results have been mind-boggling,” says Brendon Bevan, Arkaba’s manager. The water table is rising; 10 new bird species have been recorded; native grasses are regenerating, and there are now rarities to be seen such as the Gidgee skink, a large lizard, and two colonies of endangered yellow-footed rock wallabies.

So my “discovery” was less to do with the lodge itself, its succulent cellar of South Australian wines and impressive bed linen notwithstanding, than with how even a tiny tourism enterprise can help return a place to nature. The sundowners sipped on a burnished hilltop amid the shadows of sunset are helping to repair a piece of Australia.

Staying at Arkaba (arkabastation.com) costs A$890 (£434) per person per night, all inclusive

Disappointment: Strain on the train, France

One of the attractions for the growing numbers of us who prefer to take a train than fly ought to be rail’s more relaxed attitude to luggage allowances. Basically, if you can carry it, you can bring it. Make that, “if you can find room for it”. Family hatchbacks have more baggage space than the TGV I took to Strasbourg recently. Eurostar is better, but you still need to perfect your “clean and jerk” to hoist a heavy case on to the highest rack and risk turning travel rapture into rupture.

Jan Morris

Discovery: A mountain haven, Wales

For 70 years I have lived within sight of Snowdon’s southern flank, but only the other day did I discover something delightful on the other side of the mountain. The Pen-y-Ceunant Tea House is the very last building you leave behind if you are climbing expectantly into the mountains from Llanberis — or, more importantly, the very first you encounter if you are coming down from an exhausting climb or trek. It is a classic Welsh mountain cottage of the late 18th century, rough-stoned, gabled, built sideways-on to the track, and it is open all day every day of the year, with mulled wine perpetually available. Its welcome is almost eccentrically generous. Muddy boots are welcome. Dogs are welcome. Walkers are welcome to eat their own sandwiches free of charge. Children under four are welcome, and get a free drink and a cake. Everyone is welcome to 24-hour advice, posted on a noticeboard, about weather conditions and the state of mountain tracks.

Once inside, muddy boots and all, one is absorbed into Welshness. The mulled wine may not be exactly native, but almost everything else is. It is a proper Welsh living-room in there, with the statutory crockery on the essential tall dresser, and you will drink locally brewed Welsh beers, and eat home-produced Welsh cakes, creams and jams, and warm yourselves with what the proprietors immodestly declare to be, in a truly Welsh idiom, “probably the best hot chocolate in the United Kingdom”.

All in all I can hardly imagine a more encouraging farewell to banality, a more heart-warming welcome to home comforts, or just a nicer surprise, than this unexpected haven just over the mountain from me.

Pen-y-Ceunant Tea House, Snowdon Path, Llanberis; snowdoncafe.com

Disappointment: A mass exodus

My great let-down of 2015 concerned cats in Venice. It used to be one of the great cat cities — cats in every campo, cats in back-alleys, pampered cats in gardens. When I went there this year all signs of them had gone, and I encountered not a hiss or a miaow or a conciliatory purr, nor a single kind old lady with a scrunched-up bag of fish heads for her friends. The municipal truth is that, as one of the city’s beloved injunctions might have put it in the great days of the Serenissima: there shall be no cats in Venice.

Lucia van der Post

Discovery: A town-turned-art gallery, Sardinia

Sardinia’s Costa Smeralda is a wondrous place, a playground for the gilded, bronzed and privileged of this world who each summer flock to the sumptuous villas, the of-the-moment restaurants and the ritzy yachts. But there is another Sardinia, more intimately connected to the lives and rhythms of the people of the land. You need to travel to the less heralded parts to find it.

This year we ventured inland and didn’t regret it for a moment. We discovered a land where the traditions and lifestyles seem scarcely to have changed for centuries, where in many villages you can still catch glimpses of the older women in traditional dress (long skirts, headscarves, embroidered blouses), but what stunned us most of all were the murals of the little town of Orgosolo.

I went to Orgosolo in the late 1960s and remember a prevailing sense of menace that made me feel distinctly uneasy. I thought it was because of the presence of the Mafia but, no, its inhabitants insist, they were never a Mafia town. Instead, they say, almost proudly, they had banditi. It was the banditi who gave it its dark reputation, a cultural phenomenon Vittorio De Seta captured in his 1961 movie Banditi a Orgosolo. Today Orgosolo’s main street is one vast outdoor art gallery — almost every house or shop façade is covered with extraordinary murals, each highly political, in painterly styles that vary from impressionistic to naive, from pop to realistic, but all are striking and powerful in the messages they convey.

The first mural, it seems, was painted in 1969 by an anarchist theatre group from Milan, but from there the idea spread and today the murals deal with almost every social and political problem from unemployment to state oppression, from war and terrorism to local land disputes. There are workshops to raise the standard of paintings and it’s a recognised cultural phenomenon. An hour or two spent wandering down Orgosolo’s main street is a fascinating antidote to the Costa Smeralda’s shiny delights.

For accommodation and travel see sardegnaturismo.it. Sardinian Places (sardinianplaces.co.uk) offers villa packages

Disappointment: The last rhino in Mana Pools, Zimbabwe

I have had some of my most magical bush experiences in Zimbabwe’s Mana Pools national park. Bordered by the great Zambezi river, it used to pulsate with wildlife, and the thrill of tracking rhino with one of its great guides, John Stevens, is a memory that lingers. But that great lumbering prehistoric beast has vanished from the scene — the last one was relocated to the Matusadona national park for its own protection and Mana Pools is the poorer for it.

Pico Iyer

Discovery: Tofu cheesecake amid the temples, Japan

The secret heart of Japan, mysterious and grave, is Koyasan, the mystical mountain 90 minutes outside of Osaka on top of which are 117 temples, a huge grove of centuries-old cedar trees and more than 200,000 graves. You get out of a cable-car and enter a hushed and intense world in which, staying in temples and eating monks’ vegetarian fare, you can imbibe for a while the esoteric Shingon sect of Buddhism, founded on the mountain 1,200 years ago.

French and Italian visitors have begun to discover Koyasan but for anyone in search of powerful fire ceremonies at dawn and lanterned walks at night, it remains much of the time hauntingly deserted. On Koyasan itself, the discovery of the year for me was Bon On Sha, a funky “international café” on the quiet main road run by a young Japanese traveller and his French wife. Every day, they cook up one vegetarian set menu — Thai curries or spinach pies, followed by tofu cheesecake, say — accompanied by coffees, teas and other cakes. All around, in their small, high-roofed, cosy sanctuary are pots and books and poems made by the handful of others who have fashioned an alternative society of sorts around the holy mountain.

Monks from the nearby temples stop by the place and discuss eternity (or Werner Herzog). The woman next to you may be a Zen student from San Francisco. High-fashion Kyoto couples settle into what feels like a warm and communal coffee-house in Darjeeling.

I actually first discovered Bon On Sha nine years ago. But it was my great find of 2015 as well, in part because, with its constantly changing menus and art works, it seems a different place from when I saw it before, a discovery-in-progress even for someone like me, who’s lived in Japan since 1987.

Bon On Sha is at 730 Koyasan; Inside Japan Tours (insidejapantours.com) can arrange trips staying at the temples of Koyasan

Disappointment: A tourist trap, Brazil

For decades, I’ve steered clear of Copacabana, the tourist centre of Rio and therefore the epicentre of streetwalking, street crime and flavourless pizzas. But I stayed there last year, during the Ted Global conference, and the elegance of Ted seemed to magic it into the last word in comfort and style.

Impressed, I took my wife there three months later. Every time we stepped out, she got leered at or groped; urchins sauntered up to us regularly with larcenous intent; and we found ourselves taking a bus whenever we wanted to eat. You know it already, perhaps, but it bears repeating: stay only in Ipanema!

Claire Wrathall

Discovery: The perfect hotel boutique, Italy

Of all the clothes I’ve bought this year, the most admired has been a black cotton dress with a distinctive pattern of brown and white circles, with a collar, elbow-length sleeves with little cuffs, a waist cinched with a drawstring and a full, not quite circle skirt that falls to mid-calf. I’ve worn it, with heels and a necklace, to parties and dinners in expensive hotels, and over a swimsuit as a cover-up on the beach. It weighs almost nothing, scarcely creases when packed and can be washed in a machine. It is the perfect versatile holiday frock, and I’ve lost count of the compliments it’s prompted and of how often I’ve been asked where I found it. The answer is Emporio Sirenuse in Positano, opposite the fabled hotel Le Sirenuse.

John Steinbeck described this 18th-century villa as “an old family house converted into a first-class hotel, spotless and cool, with grape arbours over its outside [now Michelin-starred] dining rooms”. Steinbeck stayed in 1953, a couple of seasons after the patriarch of the aristocratic Neapolitan family that has owned it for more than two centuries began accepting paying guests. “The owner,” he noted, “is an Italian nobleman, Marquis Paolo Sersale, a strong handsome man of about 50 who dresses mostly like a beachcomber and works very hard.”

In many respects nothing has changed except that the hotel is now run by Paolo’s grandson, Antonio Sersale, who also favours informal, if impeccably stylish attire. The Emporio stands opposite the hotel on Via Cristoforo Colombo and is the creation of his wife, Carla Sersale. She designs for it herself — her swimwear is made by the same company as Chanel’s — as well as sourcing clothes for women and men, accessories and homeware (much of it used in the hotel), by other designers, from Pucci gowns to mouth-blown Carlo Moretti glass. A limited range is available online, so I now have the same dress in another print, too. Next season I may order the whole range.

Double rooms at Le Sirenuse (sirenuse.it) cost from around €300; for the shop see emporiosirenuse.com

Disappointment: A night in a cave, Italy

As recently as the 1950s the poorest inhabitants of Matera in the south Italian province of Basilicata were still living, along with their livestock, in caves, a situation known as “Italy’s shame”.

One of the longest continuously occupied places on earth, the town is an attractive place now, rich in history and decent restaurants. Hence the Swedish-Italian entrepreneur Daniele Kihlgren’s idea that some of the sassi, as the caves are known, might do as upscale tourist accommodation.

My disappointment in the hotel he has created, Sextantio, was less in the gloomy, rudimentarily furnished though not unphotogenic interiors, nor in the bathroom’s musty smell, mouldy walls and slippery floor (among a catalogue of minor annoyances), but that I had been mug enough to pay €860 to spend a couple of nights somewhere so grim. As anyone who has read Carlo Lévi’s searing memoir Christ Stopped at Eboli will know, these were places of terrible suffering, poverty and hardship. That we had come here on holiday felt wrong on so many levels and left me not a little spooked.

Tom Robbins

Discovery: A bargain ski trip, France

Skiing has always been a rich man’s sport, but in the past decade high-season prices have risen to levels to make even the wealthiest enthusiast wobble. We wanted to go on a family trip at Easter — six adults, three kids — but in the well-known resorts of the French Alps (Val d’Isère, Méribel, Chamonix) even modest chalets were asking £10,000-£12,000 a week (without flights, transfers, lift passes, ski hire . . .). Much googling ensued, alongside debates about taking children out of school in term time, until we chanced upon a chalet that looked far nicer than anything we’d been offered, but only cost £1,192. The catch was that it was in a village of which none of us had ever heard — Manigod.

Let’s be clear: for anyone looking for nightlife, bars, shopping, a “scene”, Manigod is probably the worst resort in the Alps. But with three children under seven, such things were never going to play much of a part in our trip. For us, Manigod was perfect, an introduction to a very different type of ski holiday, beyond the conveyor-belt of the mainstream ski industry. The chalet was gorgeous, with a huge open-plan living area, a balcony looking out over the roofs of the village to the valley below and the white peaks beyond; there was even a (tiny) sauna. Manigod turned out to be not really a ski resort at all but a sleepy farming village with mud from tractor tyres on the road, perhaps like Val d’Isère might have been 50 years ago. We’d walk down beside a gushing stream to the boulangerie to buy croissants each morning. There’s a small bar, with trophies from the local ski club on the wall, a church where you can listen to organ recitals on Wednesday nights, and that’s about it.

The drawback is that you have to drive to the ski area, 15 minutes up a winding mountain road to the Col de la Croix Fry. Once there, though, you find the ideal area for children to learn to ski: a mini-mountain consisting exclusively of gentle runs, many with slalom courses marked out by cartoon animals. Advanced skiers can connect via a long, snowy track to La Clusaz, where the lifts link to La Balme, a high, wild area that is the haunt of some of France’s most revered freeride skiers. With the kids deposited for their lesson, we spent an unforgettable morning off-piste with Seb Michaud, a former star of the Freeride World Tour competition who now gives masterclasses with local ski school Evo2.

Back in Manigod at the end of the day, we were ready for the Manigod version of après-ski: not a boozy night in a sweaty bar but a tour of the vaulted cellars of Joseph Paccard, an affineur to whom local farmers send cheese for ageing. We sampled reblochon after tomme after beaufort, washed down with local Savoie wine, and learnt how the cheese is aged on special spruce planks from trees cut only under a full moon. It was authentic, totally untouristy — a bargain holiday full of priceless moments.

Chalet Tournette in Manigod is available via Ovo Network (locationmanigod.com), from €1,090 (£768) a week. For more on the region see lakeannecy-skiresorts.com

Disappointment: A chaotic arrival, UK

My evening flight from Greece back to Gatwick in September had been on time; the immigration hall was empty; the luggage was waiting on the carousel. I was happily imagining getting home earlier than anticipated until I turned a corner to see queues snaking back from the airport’s rail station into the terminal. The problem wasn’t the trains, which were all on time; the queues were just to buy a ticket at the slow, incredibly complex machines. (How is a foreigner just off a long-haul flight expected to know whether they want to travel on a train operated by Thameslink, Gatwick Express or Southern?) The station itself was packed and chaotic, full of weary and bewildered travellers. I stood in the queue as train after train for London came and went, angry but also ashamed that this would be so many visitors’ first impression of Britain.

Sophy Roberts

Discovery: An adventure in the Back of Beyond, Australia

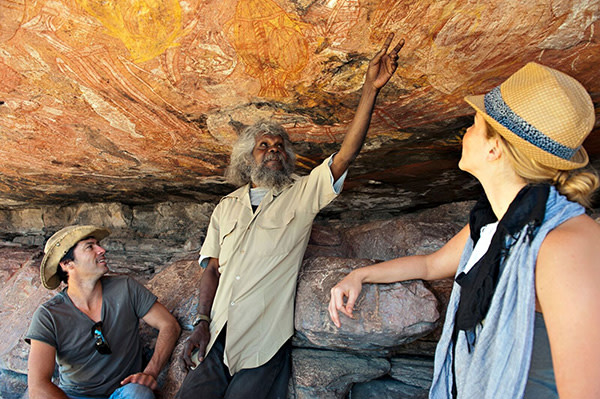

It was the words that got me first — Behind the Back of Beyond, the Land of the Never-Never — used to describe Australia’s remote Northern Territory. As I started to look harder, the names got even better: Lousy Creek, Mosquito Creek, Dead Fish Billabong. To access it, I waited two years to snag a week of Sab Lord’s time, a guide brought up with the region’s Aboriginals, who walks the ground barefoot. While his Darwin-based company arranges visits for different budgets, Lord limits his private guiding to 125 days a year.

I visited in May, on a seven-night journey in and out of Darwin. On the fringe of Kakadu national park, we weaved in an airboat through forests still flooded from “the wet”. In a few months the ground would be dried up — “as bare as a badger’s arse”, said Lord. We wove through silver paperbark trees — part enchanted forest, part Japanese water garden, the water carpeted in blush-pink lilies. At one camp, I woke up to wallabies grazing beneath corkscrew pines. Wild bush horses galloped in and out of frame. Termite nests rose out of the ground like towers from a fairy tale. In last light, they cast long shadows across an expanse that reminded me of Africa, except no one else was around.

Around campfires, we listened to stories of Lord’s childhood pets — including a buffalo called Alan Quirk he liked to ride — as we feasted on spare ribs doused in sugar and flames. We hiked in hidden gorges. We swam in remote creeks. We slept under the moon and woke to the din of kookaburra.

We drove on into western Arnhem Land where we explored sites covered with Aboriginal rock art. We took a boat into remote billabongs, into whispering spaces where the “dreaming” stories of the Aboriginals started to take hold. In a cave near Mount Borradaile, ghosts floated off painted walls — rainbow serpents, men in boats — recalling 50,000 years of human life in a hole in the map, far, far Behind the Back of Beyond.

Epic Private Journeys (epicprivatejourneys.com) offers a seven-night privately guided trip to the Northern Territory with Sab Lord from £8,000 per person

Disappointment: Provence, France

I was the guest of my brother-in-law, in a spectacular villa he rented close to Aix, so I should be careful not to sully a future invitation. This part of France may be full of honeyed hilltop villages and fields of lavender, but in July it is overwhelmed by fellow English. Even our villa’s chef was a Brit, who duly murdered the beef. How disappointing it was to discover not even the Gallic command of the kitchen is safe.

Photographs: Alamy; Jochen Schmidt; Michael Howard/Four Corners; Bob Jones; Dreamstime

Comments