Lost in headspace: the rise of the home temple

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Mexican artist Bosco Sodi spent several years persuading the great Tadao Ando to design Casa Wabi, his Oaxaca art foundation sitting on a 90-acre plot of coastline between the mountains and the Pacific. There is, as the Pritzker Architecture Prize jury said, “never a predictable moment” with Ando, and Sodi describes his excitement as he waited for the eventual proposal from the Osaka-based architect.

Sodi is not religious, baulks at the word spiritual and does not meditate. Nonetheless, his dream for the foundation, completed in 2014, was that it be an escape from the monkey mind both for his family and for visiting artists. “Including a place for reflection, contemplation, introspection,” he says, was an essential part of the brief, which also included a swimming pool and an 8,000sq ft art gallery. Ando, famous for the transcendent poetry in his sacral architecture, such as the Church of the Light in Ibaraki, proposed a naked-eye observatory as a meditation and reflection space. It is simply a tube, cast in Ando’s signature silken concrete, standing 10m high and 10m across. “It leans at a 60-degree angle towards the sea; this bounces the sound of the waves so it seems as if they are going to break over you from the mountain’s direction,” explains Sodi. “The effect is both humbling and confusing – in a good way. The nights are very clear here; sitting inside the observatory, all you can see is sky. The first time I entered was a beautiful experience.”

The structure epitomises the physical and mental luxury of a private space dedicated to stillness. Where once there were private chapels, today there are meditation pavilions, yoga shala and temples devoted to silence and ceremony. This approach to sacral architecture is not about religion, and more about a personal spiritual practice.

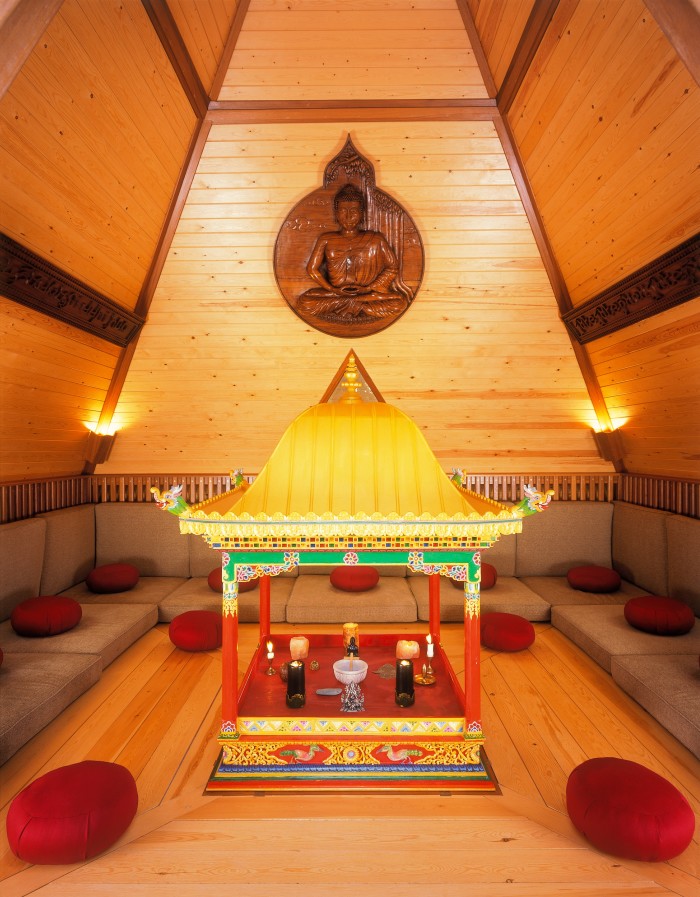

At the Cowdray Estate in West Sussex, with its polo club that hosts the Gold Cup for the British Open Polo Championship, Marina, Viscountess Cowdray and her husband, Michael, the 4th Viscount, built a meditation pyramid below an avenue of 150-year-old giant sequoias. “It has been a saving grace for me,” she says. “My husband and I love to meditate together there. It’s not grand. My husband drafted the plans and it was built by the guys here at Cowdray in a hardwood that could endure British winters.” The altar table was a gift from a friend, the Bhutanese Rinpoche: “His Holiness the 12th Gyalwang Drukpa dedicated the pyramid in 2000. He asked for the dimensions and had the altar built to fit.”

In 2016, the Rinpoche also blessed a deconsecrated chapel on the 16,500-acre estate, used by the community “for meditation, Qi Gong and yoga... but also for community activities such as plant sales. We live in a small Christian community and it could have been perceived as a bit ‘out there’ and, at first, I think a lot of people thought we were crazy. But we keep it all as normal as we can. We aren’t burning sacred woods or ringing bells; it’s not about the ‘stuff’ and the distractions and the kit.”

This lack of “stuff” is a sentiment echoed by interior designer Joanna Plant, who “can’t abide the Buddha-at‑the‑end-of-the-pool-type thing, which is just meaningless ostentation and decoration. Carving out a space away from the domestic humdrum is very different. It’s not about display, it’s about creating physical distance between the self and our quotidian personality and roles in the world.”

James Fox, a former marketing manager of Green Retreats, which builds flat-packed outbuildings and garden rooms costing up to £33,000, says that after home offices and home gyms, the domestic yoga and wellness space has been one of the most popular enquiries since the lockdowns began. Site visits to the category increased by more than 1,250 per cent in the first three months of 2021 compared to 2020. The home retreat isn’t quite the new home cinema, but it is a rising trend, and a more regular presence in an architect’s brief. Take actress Cate Blanchett, who reportedly recently applied for planning permission to have outbuildings at her East Sussex home turned into an art gallery, home office and meditation room.

Francis Sultana, the decorator darling of the high-net-worth art collector, says: “Increasingly clients are looking for a space in their homes to attend to spiritual matters – whatever that may mean for them, the requirements are the same. It must be minimal yet warm and a complete break from the colour and artwork in the rest of the home.”

At property entrepreneur Anton Bilton’s Sabina development in the south of Ibiza, the international mix of residents have access to an 80ft pool with a private nightclub underneath. It’s not that unusual for the island, where it’s standard for high-end new-build homes to come with spas and a discotheque. Where Bilton sets himself apart is the “non-denominational temple of gratitude”, which has already been used by residents for a secular interpretation of a Bar Mitzvah; a cacao ceremony, in which the mildly mind-altering powers of the raw beans are paired with guided spiritual journeys; and a holotropic breathwork session.

Bilton has used a mix of starchitects such as Rick Joy, John Pawson and Sir David Chipperfield for the residences, but for the temple he turned to Rolf Blakstad, the island’s most sought-after architect for intelligent takes on the island’s vernacular. Blakstad underpinned his designs with sacred geometry. The space “is accessed between two pillars, and down a few steps reminiscent of those left by Phoenicians on the island”, he says. The footprint of the temple is a figure eight. The first circle is an amphitheatre in limestone, while the main temple space is accessed “via portal ramps sloping down into a sunken dome with water channels on all sides – for cleansing in all senses. The dome itself is a scale replica of the Pantheon and has a remarkable echo that vibrates through the body and is designed to aid contemplation.”

In India – where the home temple, even if it is just a nook in an apartment, is a cultural norm – the idea is evolving. In the Palghar district of Maharashtra, about 50 miles outside Mumbai, architect Saket Sethi was briefed for a private house with a temple as a surprise gift for the high-profile private-wealth lawyer, Nishith Desai, from his wife, Swati. “The Desais are one of the wealthiest families in the country, but they are from a humble background and haven’t forgotten who they are,” he explains. “They wanted a house and a space where they could be inspired and thankful for life. The husband is not religious, while the wife is a devout Hindu, but they were both looking for what you could call a spiritual strong room, a space where they can go and recharge.”

What makes Sethi’s Sunoo Temple House unusual is the relative proportions of the two spaces. The egg-shaped garden temple, wrapped in a swirling iridescent galaxy created from 1.3 million blue and gold Bisazza tiles, contradicts a Hindu belief dating back to the fifth century that domestic temples must not be seen. Sethi “decided to make the relationship between man (the house) and God (the temple) – whatever that may mean to you – manifest. The temple is taller than the house.”

Sethi’s practice has offices in Mumbai and Barcelona. He observes the eastern norm for spiritual spaces in domestic settings gaining traction among his clients in the west. “A yoga room, a sun room, a detox room… whatever you call it, more people are looking for something that will help them feel better. It is not just about meditation. The west has always had extraordinary buildings built to ask what ‘God’ meant, yet new buildings forget that conversation man wants to have with the metaphysical. It is not enough to just have your family, make your money, own your things. I want people to have an elevated moment.”

For Robert Seaton, one of the first figures in Bourne Leisure, which was recently sold to Blackstone for a rumoured £3bn, that elevated moment is found through meditating – something he has been practising for 50 years. “I’ve always found time for it,” he says, “but I’ve never had a special place I went to do it.” Joanna Plant Interiors was part of a team that converted a cavernous basement in his Georgian-period Hampstead home into a space decorated with crystals and fossils, some very large, bought from Dale Rogers Ammonite in Pimlico.

Seaton and his wife Jo intended that the new space, which came up when the footings of their house needed replacing, should have multiple uses. “It became this place where we went when feeling scratchy and difficult, to just let go and smooth out the wrinkles. People with busy minds, they don’t get it. But other people, the minute they go in, they just fall into the stillness. Once I had a base, a space to meditate, I didn’t ever think of going anywhere else. Twice a day, I’d feel a pull. It’s never been used for anything else. It’s a wonderful place.”

Comments