Scorsese, De Niro and a quartet of mob masterpieces

Simply sign up to the Film myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

What on earth do you call a quartet of films about gang violence, made by the same director with the same star actor, which forms a unique, rich, incalculable art-blockbuster for our times? A bloody masterpiece? The Wring Cycle (strangulation being a regular feature)?

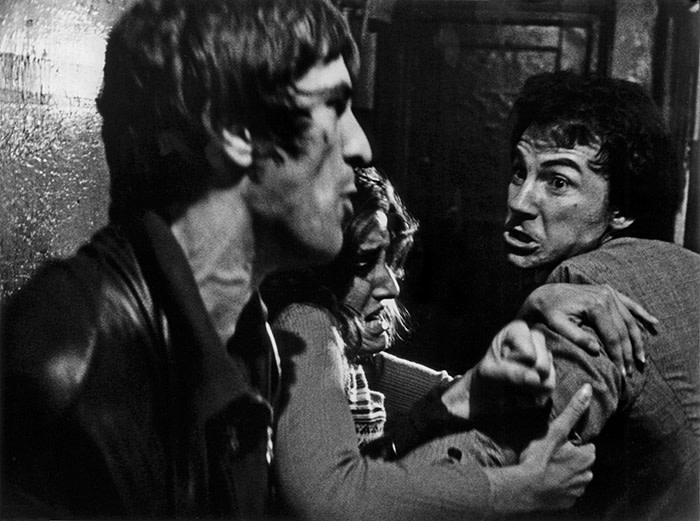

Martin Scorsese and Robert De Niro are answerable for many films. But there’s something deeply special about their gangster dramas. This canon now spans nearly half a century, from Mean Streets (1973) to The Irishman (2019), with Goodfellas (1990) and Casino (1995) completing the tetralogy. (Credit Nicholas Pileggi too, source author and co-scenarist of those middle films, whose Mafia-buff expertise surely buffed up their authenticity.)

We dare not expect a fifth mob masterwork. De Niro and Scorsese’s combined age is now 152. But then we didn’t expect The Irishman. That movie, soon to reach all parts of Planet Moviemania, shows no sign of dwindling craft, passion or dramatic energy.

Passion. That’s what in essence they are, these dynastic-fraternal-litanistic pageants of good and evil, love and hate, fellowship and felony: passion plays. Casino’s music begins and climaxes with Bach’s St Matthew Passion. Add The Irishman’s redeployment of Peter Gabriel’s “Passion” from The Last Temptation of Christ. Add, from earlier days, Mean Streets’ “Munasterio ‘e Santa-Chiara”.

Why are we beginning with music? Because that’s what this cinema is: music even when there’s no music. Amid the visual bloodbaths abounding in Scorsese and De Niro’s gangster canon, it’s impossible to forget that Scorsese is, first, a Catholic — with all the accompanying baggage of martyrdom themes and blood-atonement motifs — and, second, a stylist steeped in the aesthetics of music.

His camera is seldom still: it moves to ballets of meaning. Look at those virtuoso tracking shots that make a dance path for his characters through streets or kitchens, through hell-lit casinos or hotel corridors. Look at his montage sequences too: those passages that concertina narrative to the sound of chart favourites precisely evoking a place, a time, a mood: from pop to rock to God-slot-classical.

Those montages can be filled, simultaneously and competingly, with voiceover narrative. But that is another Scorsese idiom done with such rhythm and flair that it can be called music. (Count the bad thrillers by other directors which have drowned in the prosy use of voiceover.)

We could add The Departed and Gangs of New York to the gangster grand oeuvre. But they don’t have De Niro and that’s the difference. The Bob-and-Marty teaming lights a whole other fire under screen storytelling. DiCaprio, Damon and Day-Lewis are all good tinder. But De Niro begins his roles at crackle intensity, then sustains it, while never burning himself out.

It’s an irony I have always loved that in his first film for Scorsese, Mean Streets, De Niro played Joe Pesci, in effect, to Harvey Keitel’s De Niro. The young RDN as “Johnny Boy” gets the volatile, nitroglycerine character — the hellion responding with violence to every provocation — while Keitel is the suavely smouldering capo agoniste. Keitel plays a younger version of the role that his co-star came to make his own in Goodfellas, Casino and The Irishman. De Niro saw, by intelligence or instinct, that a steady-state protagonist was more interesting, more multivalent, more “dangerous” in his withheld incendiary threat, than the big-bang showman delinquent.

What is the heart of this great filmic four-pack? It’s the theme of love deranged; of what happens to love when it is frustrated, denied or corrupted. Everyone wants to love everyone. That’s the core and cuore of Scorsese’s Italianate-American world. But love here is on the borderline of sanity. When it goes mad, it becomes fanatical, fissile, partisan and loyalty-obsessed, and the Mafia is born. (Not just the Mafia. The Murphia in The Irishman. Kosher Nostra in the Jewish modulations of Casino.) You can’t love everyone; so those you can’t love get the hate.

Trust is the creed and criterion. Four consecutive times, outnumbering St Peter’s cock-crow catechisings, De Niro asks Sharon Stone in Casino: “Can I trust you?” He can’t. Exit love; enter hate. Which in these stories includes love, since the final tribute paid by famigliari to their foes is to hug them to death. Count the times mortality is delivered with an embrace. In The Irishman (and here comes a major spoiler), De Niro holds close the head of Pacino’s Jimmy Hoffa to fire the bullets into it. When Joe Pesci kills the “Anna Scott” character in Casino, he cradles the bleeding head as it lolls into inertia. He seems to want the blood to libate and purify the ground.

It’s a man’s world. Women don’t get much of a look-in. They are wives or girlfriends or mothers. Family business with a small “f” is the female role. The one exception is Stone’s part in Casino, which may be the best part ever written for a woman in a gangster movie. It’s a crash course through a single life concentrated into a particle-acceleration hurtle through a single tragic marriage. Scorsese portrays the legacy of love deformed. Of love undone by money, murder and the quest for power. Of love undone because it seeks to express itself, even sustain itself, through money, murder and the quest for power.

The Scorsese gangster world isn’t just chastening and cathartic. It’s funny too: funny-appalling. These are black comedies to rank with Ben Jonson’s Volpone. The great serio-hilarious scene has to be Pesci’s baiting of Ray Liotta in Goodfellas. “You think I’m funny? ” Our terror goes to the edge; peeps over the edge; gets vertigo; thinks it’s going to die. Then the prick bursts the balloon: he’s joking. (Pick your meaning of prick.) Nearly everyone is that in these films. But they’re pricks so grand or uproarious, so complex or troubled, that the achievement at best is not Jonsonian, it’s Shakespearean.

I still can’t believe, four decades on, that I once went to dinner with an American couple who ran a chain of London cinemas and whose other guest was a voluble, short-statured, thirty-something Italian-American film-maker — then barely known — who had a bad dose of asthma. This must have been in 1973, maybe 1974. He kept inhaling a puffer. He talked too fast. I suspected he would burn out by 40. He was going on about some movie he was distantly planning with a young actor, also barely known, in which a psychotic taxi driver roams New York looking to set the world to rights . . .

That was my first meeting with Martin Scorsese. He is still here. So is De Niro. And Taxi Driver lives on as an unsurpassable pendant to a great screen gangster saga. Which proves that the world is as unpredictable, exciting and miraculously maladjusted as these two men have set out to show in their crime films. Sometimes that world just lucks out. And we all benefit. Especially if we like going to the movies.

‘The Irishman’ is on release in the US now, has its UK release on November 8 and is streamed on Netflix from November 27

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Listen and subscribe to Culture Call, a transatlantic conversation from the FT, at ft.com/culture-call or on Apple Podcasts

Comments