Letter from Ukraine: the language of war

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

At the beginning of March, a Theatre of Playwrights was supposed to open its doors in Kyiv. February 25 23:59 was the deadline for the competing writers whose new plays would be considered for the grand opening. Topic: “Anxiety”. The competition statement implied that everyone understood what kind of anxiety it was, and who might be the cause of it.

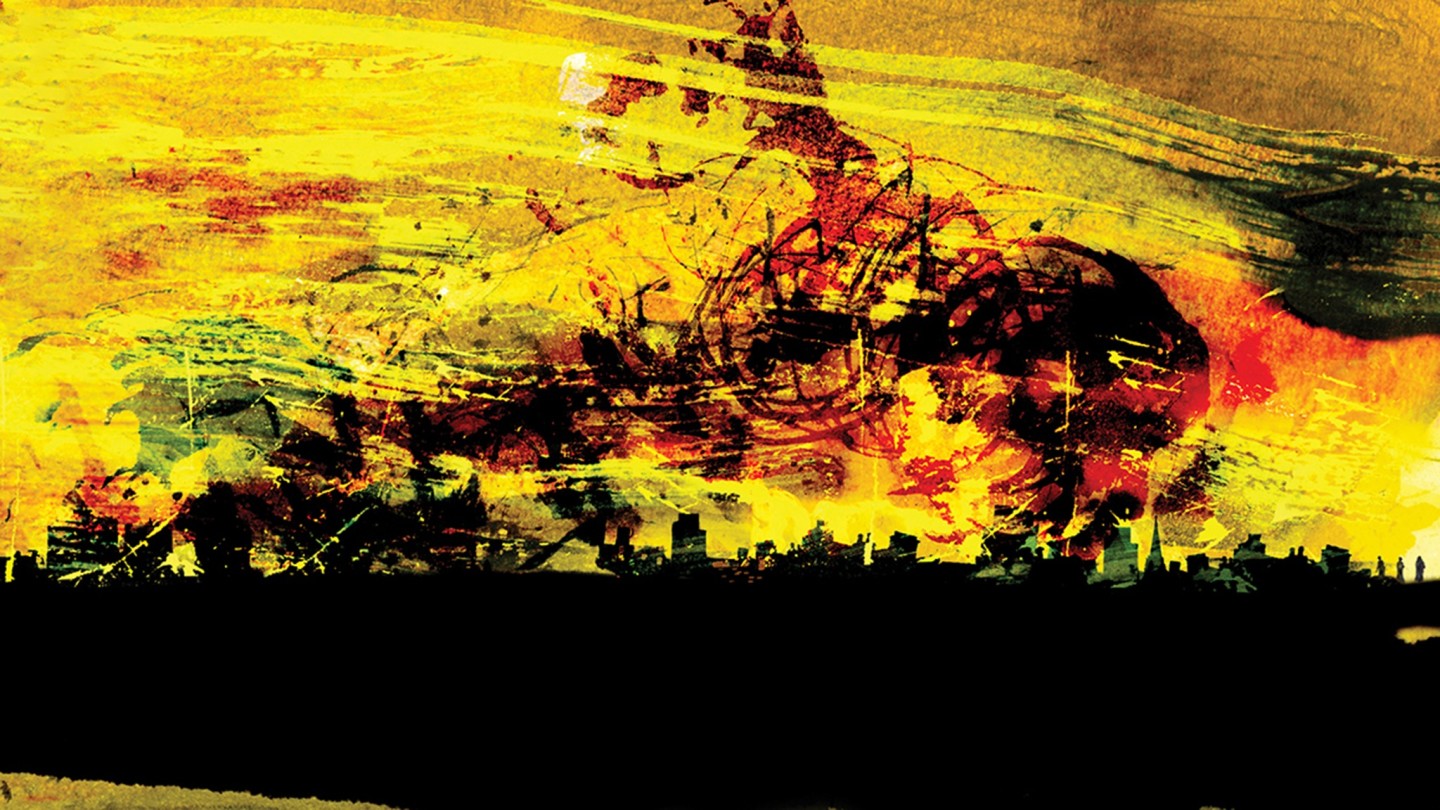

I dearly wanted to be part of that initiative and write my first play. To describe the feelings, preserve the exact moment in time. I had a certain picture in my mind — enormous, limitless black clouds of chaos swirling above our heads. Tentacles of endless Lovecraftian cthulhu, crows’ wings flickering in the darkness. I didn’t get to finish the play, but know for sure that close to the ending there would have been a scene reminiscent of a familiar Hollywood image — a powerful ray of light cutting through the darkness. However, unlike the Hollywood cliché, this darkness is total emptiness. This is chaos feeding on chaos. This is nothingness in its entirety.

I didn’t get to finish my play because on Thursday I was woken up by war. Chaos woke me. And the noise of Russian helicopters.

My wife and I have a house in Hostomel, a town near Kyiv, the name of which is now known around the world. Ukrainian soldiers battled for Hostomel’s airfield — one of a hundred episodes that now contribute to the foundation of a new Ukrainian reality.

On the second day of the war, I started to receive messages from my neighbours that a group of armed Russians were breaking into our homes. They were bringing people out of their houses, pointing guns to their heads, forcing them on to their knees, then making them leave.

The forest close to our house is a special place. A few years ago, a group of neighbours, including my wife and I, were fighting against an illegal redevelopment of the forest zone. We lost that battle against the local “little tsar” and his bought-for-money “sportsmen”, known as titushkas.

Russian occupants took up positions behind this development, a supermarket, in this very forest. But there is one thing they did not comprehend: it doesn’t matter how much Ukrainians “chubytysia”, or quarrel, among themselves (the word “chubytysia” literally means “to pull the hair of the other cossack”) — in the face of the enemy we are one. Whether an activist who is protecting the forest or a titushka who is propping up the “little tsar”, we will confront the enemy together. Just as we did hundreds of years ago.

Every one of us has got a list of things that we will never forgive this war and its occupying forces for. I opened my count on that first morning. It started with a chat with my mother — her windows face Hostomel’s airfield grounds, near to where my wife and I have our home. She is a university professor, a specialist in ancient literature and 19th-century American writers. We had a telephone conversation just after the first raid on the airport.

And the same voice that used to sing me lullabies was now saying over the phone: “Son, first, second, fourth, seventh, 10th helicopter. Dear Lord!” Then she told me that she had just seen Apocalypse Now unfold in front of her very eyes.

I shall never forgive them for this. Every one of us has a list — it is endless.

At this moment in time the whole country is one co-ordinated body. Goodwill is everywhere. You won’t see arguments at petrol pumps. You won’t witness breaches of traffic rules.

How long can the first day of war last for? For my wife and me it was 34 hours.

My social media is tuned in to official information channels. We applaud Ukrainian media who have united in the marathon supplying objective information to the public. They announce when a strategic object has been lost. And promptly inform us if it has been regained.

Eight years of Russian-Ukrainian conflict on our eastern lands and the annexation of Crimea is finally recognised out loud — this is a war with Russia. And their officials cannot say “there are no Russian troops in Donbas”. Eight years of war crimes against the Ukrainian army, Ukrainian citizens, international laws and humanity. We remember the 283 passengers and 15 crew who perished on Malaysia Airlines Flight 17, shot down on 17 July 2014 while flying over eastern Ukraine.

We no longer need to explain why it is Kyiv and not Kiev, why it is now a “Russian invasion” and not a “crisis”.

A few days before the war, my wife and I had dinner with a few “cyborgs” (slang for the servicemen who defended Donetsk airport in 2014). They don’t mince words when talking about war with Russia. After every expletive they apologised for using this language of war. It’s the language in which everything has its own name.

War is war — not a military “operation”.

“Go fuck yourself!” — that was the response from Ukrainian troops to the Russian warship that bombarded Snake Island, a strip of land in the Black Sea.

The greatest consolation just for a present moment is knowing that your loved ones are OK, that the city has held, and that the Russian invaders are being repelled.

On my news feed this week I saw a post by a Russian literary critic, an intellectual. What have her posts been about since the beginning of the war? About books that allow you to escape from reality. Instant block.

Russians and Russian artists of any kind must realise: this war is also theirs. While this war is on, not one of their films should be presented at any film festival. None of their books translated. Not a single retrospective of Russian classical art should be exhibited in any museum. No republication of Dostoyevsky should see the light of day. No film financed by Russian money should be screened.

Nobody needs their work as long as artists and journalists are holding weapons in their arms to defend their land and gathering in bomb shelters under cultural institutions.

We need your voices in foreign media. Not just the avatars on Facebook but calling things what they really are. War is war and Putin is a murderer. We need your presence in the squares and streets of Russian cities. We need your money for the Ukrainian army which will put an end to this chaos. In Ukraine, the name of the war criminal who started this is now being written without a capital letter, like a name of a disease.

Voices of Ukraine

Read more personal accounts of the war in Ukraine:

Kyiv diary from journalist Kristina Berdynskykh, who asks: ‘Was I right not to leave?’

Novelist Haska Shyyan on telling her daughter about the war

An interview with film-maker Sergei Loznitsa, who says ‘Lies bring us to the catastrophe we are facing’

What can each foreign person do now? Call upon their governments to give Ukraine financial, military and diplomatic assistance. Call for the closure of the airspace over Ukraine. Help with settlement of our refugees.

Give maximum media coverage to the Russian attack on independent Ukraine and to the fact that Putin’s logic is beyond limits of dystopia and absurdity. This is the war that the Russian government can’t even justify to its own zombified population.

Organise action, demonstrate in front of Russian embassies and consulates. Use the media — every second the world needs to be reminded that a cruel and evil war against a democratic country is raging in the centre of Europe.

Donate to the Ukrainian army.

Refuse any collaboration with representatives of Russian businesses, politics, sport, industry and culture.

Don’t forget how Belarusian officials betrayed Ukrainians and allowed hostile forces to break the border.

Don’t sell Russian goods in your shops.

Any country that sows chaos must be kept in complete isolation. People must realise that this war concerns everyone. This chaos will spread, it knows no limits.

All over Ukraine, people are helping those, like me, who managed to get to safer locations. The battle is still raging in Hostomel. In the cities, civilians are making Molotov cocktails.

I look through the library of our hosts and I feel safer recognising the same spines on their shelves as I left on my own.

Our amazing neighbours have stayed in their houses, holding the community together. And there is no literature more important than their chat on Messenger right now.

My parents are spending another night in their basement, in a makeshift bomb shelter, in the company of their neighbours and their black cat who my dad calls Zina and my mom calls Babychka.

Babies are being born in bomb shelters while Russians are firing at the hospitals.

We don’t understand what day of the week it is, but we count days of war.

This is a war of a whole nation.

I have never written political essays. I generally find texts like these too temporal, too full of hot air and pathos. Not enough nuance. But right now I want to anchor this moment in time and place. The moment when the whole country is one entity. And the only language that can be spoken by a Ukrainian writer and every Ukrainian is the language of war.

The play that I wanted to write about “Anxiety” in premonition of war should have had a refrain: The Four Primary Rules of Firearm Safety, echoing what is being taught during the first lesson of handling firearms. I’d never held a gun in my hands till February 2022. My wife and I had several hours of training just to figure out what to do with it. Just in case. And now I regret like hell that I didn’t do that training before.

© Oleksandr Mykhed. Translated by Marina Gibson

About the author

Oleksandr Mykhed is a writer and curator of art projects. His non-fiction book ‘I Will Mix Your Blood with Coal’, an exploration of the Donbas and the Ukrainian east, is forthcoming in English translation and is available in German, published by Ibidem. He is a member of PEN Ukraine

Follow @ftweekend on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first

Letter in response to this article:

Can’t we drop flowers from above to end the war? / From Wolfgang Steininger, Starnberg, Germany

Comments