The power of seeing

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

“It’s not a tribute that I feel is about me!” Sarah Elizabeth Lewis is expressing her surprise at receiving a special award at Frieze New York from more than 50 galleries and institutions in recognition of her work in creating the Vision and Justice Project.

She explains: “That’s to say, the project is about shining a light out towards other work that is being put on display at galleries and amplified by museum initiatives. It is meant to salute the work that has come before me, and is pointing outwards to the work of artists [past and present].”

The project grew from Lewis’s course at Harvard, where she is associate professor in the Department of History of Art and Architecture and the Department of African and African American Studies, centred on “how visual representation in the arts has limited and liberated our definition of American citizenship and belonging.” In the course she wanted an excruciating gap: a structure for thinking about the connection between art, law and justice, and to show how culture was used in the history of racial justice in the United States.

“Every time we look at a work,” the New York- and Cambridge-based professor tells me, “there are ways in which our perception can change. The work of art and culture for justice is often private, and as culture becomes one of the few bridges we have in this increasingly polarised society to connect with those unlike ourselves, culture is being freighted with some serious work, and many artists are up to the task.”

Her personal history played a significant part in the project’s formation. “My name, Sarah Elizabeth Lewis, is meant to honour my grandfather, Shadrach Emmanuel Lee. It was my relationship with him that oriented me towards thinking about the role of culture and the arts in determining our notion of belonging and who counts in our society.”

The story of Lewis’s grandfather richly illuminates what is at the heart of the project. She tells me how in 1926, in New York, while in the 11th grade, her grandfather asked his teachers why the world surrounding them wasn’t represented in the history books. To which, Lewis says, his teacher effectively replied, “[African Americans] had done nothing to merit inclusion.” When he didn’t accept that answer and continued with his questioning, he was expelled from high school for his impertinence.

Her grandfather never returned to school, but went on to become a jazz musician and painter. “He began to create images which he knew he should have been able to find in those textbooks.”

“Because of my relationship with him, I began at a very young age to ask questions . . . and [by the time] I was in college studying the arts, I had a clear sense that there was a truth about the function of culture that was being left out of the conversation. So here I am, two generations later, teaching at Harvard the very topics that my grandfather was expelled from school for asking about.”

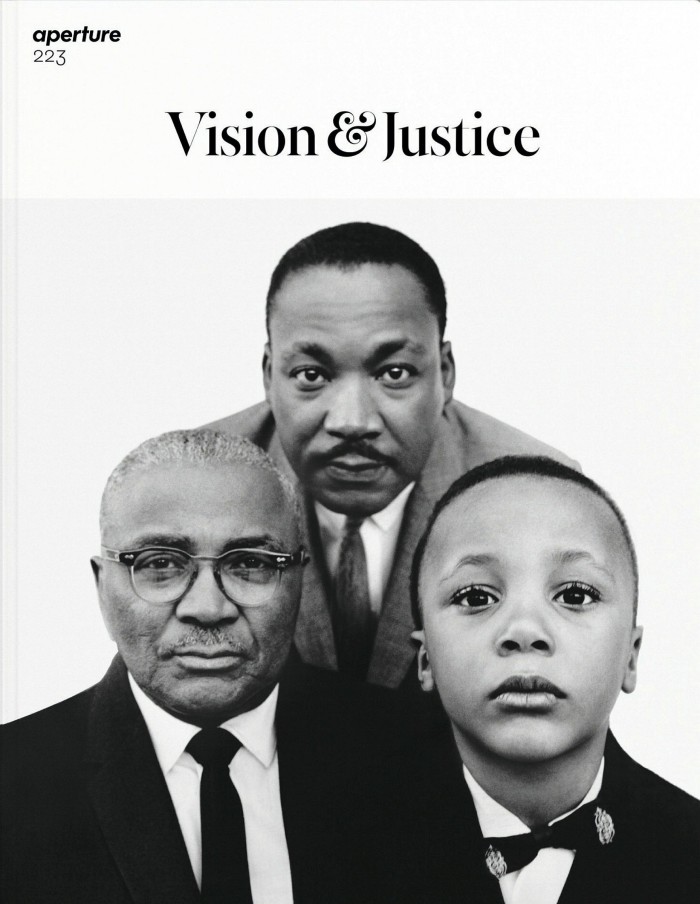

Next came Lewis’s “Vision and Justice” issue for Aperture magazine in 2016, which went on to win the 2017 Infinity Award for Critical Writing and Research from the International Center of Photography. Since then, Lewis has expanded the project beyond the classroom into a civic curriculum, a 2019 public programme, and a series of lectures and forthcoming books, and it now extends to wider inquiry into civic life and the creation of the body politic in America. How, she asks, “is the foundational right of representation in a democracy — the right to be recognised justly — tied to the work of images in the public realm?”

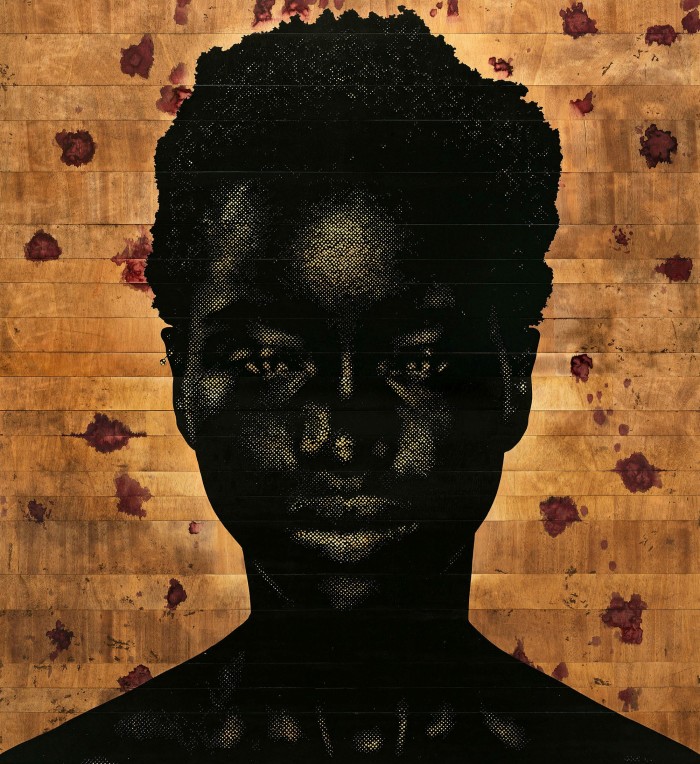

In the seemingly disparate sectors of justice and the arts, there is an invaluable role for scholars like Lewis: caretakers of culture and of minds, who know the transformative effect images can have on both our self-understanding and our understanding of others. Equally important is the valuing of images offering alternate narratives of who counts in society, and of the humanity and personhood of black people.

This is what Lewis calls representational justice — effectively, the use of images to create new narratives that positively affect and transform cultural literacy about black life. Her historical framework, her woven cord of focus on art, law and justice, make the Vision and Justice Project a notable and individual work of growing acclaim.

Lewis’s scholarship is irrevocably tied to the visionary work of the 19th-century American abolitionist and statesman, Frederick Douglass, who was one of the first in America to publicly suggest the connection between images, culture and true democracy. In his civil war speech, “Pictures and Progress”, Douglass spoke at the onset of the photographic age, of the power of images to alter our imagination for the better, and eventually effect progressive change in America — and, as Lewis puts it, “the critical imagination as a crucial apparatus for democracy.”

Lewis likens the work of the project to looking at “a journey over centuries from 1790, when the Naturalization Act [in America] determined that citizenship would be defined as being white, being male, and being able to own property, to the current day. The project interrogates how representational rights have or haven’t changed since 1790, in ways beyond legal wording.

“We do consider the function of culture, for injustice, in the context of propaganda. But restorative justice, representational justice, we don’t think about it in the positive sense. And when we do, it’s anecdotal or it’s episodic. It’s not linear and structural and embedded in how we actually teach the discipline of art history. Nor do we adequately consider the way in which aesthetics work to structure our understanding of race itself.”

The ensuing question then is, how does art and culture do this? To answer, Lewis begins by pointing to one of the more powerfully illustrative examples, that of how the broadside of the Liverpool slave ship Brookes was used in the 18th century to visually convey the inhumanity of the slave trade. Lewis speaks of this “aesthetic force,” a way of describing the internal shift that can happen when we encounter a visual image that transforms the way we perceive or think about something.

Lewis believes that today, the main work of our society, American society in particular, is “to see whether we can summon the collective will to achieve any semblance of what’s fully meant by the 14th amendment, in terms of honouring all those in the United States as having equal protection under the law. We often see the arts as a kind of luxury, as respite from these topics with such gravitas. I simply don't have that delineation in my mind because historically I know it’s just not true. The arts have always been central for these ideas that have been forerunners to what we then codify and define as the law.”

“What thrills me is that this framework [of the Vision and Justice Project] can help us all come together around what has always been the common mission of the arts, which is to honour one another, as we are honouring those artists who are working towards representational justice.”

With several publications forthcoming, Lewis aims to keep the project flourishing for generations to come.

Comments