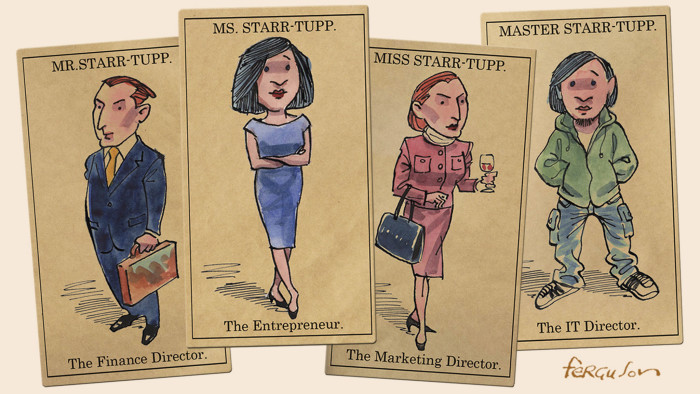

Family concerns come second to cult of the entrepreneur

Simply sign up to the Business education myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

In the US the family-owned enterprise seems to be the poor relation of the business world. Entrepreneurs such as Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon, and Mark Zuckerberg, who founded Facebook, are household names. Becoming an entrepreneur is the fashionable route that many want to travel.

As a result, business schools are geared up to teach students how to launch their own companies. The ethos is that entrepreneurs, not families, create jobs.

“I would say culturally, in the US, we put the entrepreneur on a pedestal,” explains Andrew Keyt, executive director of the Family Business Center at the Quinlan School of Business at Loyola Unversity Chicago. He is also president of the North American branch of the Family Business Network.

Mr Keyt says the US romanticisation of the entrepreneur could be contrasted with how the media has treated stories of family businesses. “I think our media just loves to tell the stories of family fights …rarely do you hear the stories of family success,” he says.

But many family business experts think that the emphasis on entrepreneurs could be misplaced.

“We have research in the United States that shows that 77 per cent of new ventures start as family businesses and another 3 per cent become family businesses within two years of being established,” says Pramodita Sharma, global director for the Successful Transgenerational Entrepreneurship Practices (Step) project at Babson and professor of family business at the University of Vermont School of Business Administration

The secret of this large percentage is in the small print. The researchers, she says, included any company in which family members have made significant contributions in terms of finance, human capital and social networks. With the net cast more widely, more entrepreneurs suddenly looked suspiciously like a family business.

Greg McCann, founder and director of Stetson University’s Family Enterprise Center, also thinks such businesses have an image problem in America.

“In the US everyone wants to identify themselves as an entrepreneur,” he says, adding that it is almost as if people want to say: “We’re not a family business, we like to do things properly.”

Mr McCann says the current image of a family business in the US is a serious drawback because of the large numbers of companies involved.

“Especially in the US, families are managing their businesses alone. The best numbers we have are that two out of three businesses fail – what if we helped them?” he asks.

Most experts agree that crucial to further development of advice and education for such enterprises is further research.

Some experts are beginning to look beyond the high rates of business closures and view them not as failures but as cashing in on a successful entrepreneurship or young family business.

For example, David Robinson, professor of finance at Duke University’s Fuqua School of Business, thinks the headline statistics may be misleading. Many companies that go out of business are sold rather than going bankrupt, he says.

“Research shows that if your parents were entrepreneurs you’re more likely to want to be an entrepreneur yourself,” says Prof Robinson.

He says US parents are understanding of children wanting to pursue their own path and might be prepared to sell their company to raise money for their offspring to start a business.

Ann Kinkade, who founded the lobbying group Family Enterprise USA about five years ago and now runs her own family business consultancy, Lucid Legacy, agrees. “Entrepreneurship is part of our culture,” she says. “What happens in the US is that we think of supporting the next generation in what they want to do.”

Ms Kinkade thinks that her previous role lobbying for family businesses became slightly easier after the financial crisis, when legislators and regulators began to notice that family concerns tended to engage with their communities better and hold on to employees for longer.

A general rethink has also been noted by Prof Sharma: “The negative bias against nepotism is clearing.”

As perceptions of family businesses improve in the US, so too does the status of research and education relating to this sector.

“I do think that there’s increased focus on the importance of values and ethics in business education and that naturally leads to an emphasis on family business education,” says Mr Keyt.

…

He says he sees business education as falling into four broad categories: graduate, undergraduate, executive education and, finally, seminars and outreach programmes. Until recently, he adds, family business education in the US had largely fallen into the last category.

“Provision has steadily been increasing towards more provision in degree courses,” Mr Keyt says, adding that the status of family business education was being helped by the improving status of research published on family business topics.

However, he concedes that progress in education in this area still has a long way to go. In contrast, he says the teaching of entrepreneurship is 20 years ahead of family enterprise in US business schools.

For Prof Robinson, however, that is just how things should remain. Unlike some of his academic peers who have homed in on issues such as family conflicts and how successful family businesses resolve them, Prof Robinson believes that when deciding on a business strategy it should be immaterial if you are working for a family member or not.

“I think if my school put forward a proposal to start a family business course and it was down to me, I would veto it. It’s anathema, apart from possibly on a tax-planning perspective.”

Comments