UN deputy secretary-general Jan Eliasson on Syria and Iran

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Last December, when Jan Eliasson, deputy secretary-general of the UN, made a pit stop in Beirut to review regional fallout from the escalating Syrian crisis, 150,000 refugees had already streamed over the Syrian border into Lebanon. “The figure is now 760,000,” says Eliasson, talking from the sofa of his New York apartment.

While the spotlight is now on UN negotiations over the Russia-US brokered deal to disband Syria’s chemical weapons, Eliasson is also focusing attention on the humanitarian crisis: the plight of two million Syrians fleeing war into neighbouring Lebanon, Jordan, Turkey and Iraq.

“There was a long period when many of us at the UN felt a deep frustration that the war went on . . . and we did not have a unified Security Council resolution to make it easier for Lakhdar Brahimi [the UN special envoy for Syria] to start the political process. Now that we have a growing unity on the need to safeguard and destroy these chemical weapons, the next step is humanitarian access and the beginning of political talks,” he says. “It’s critical.”

On a cloudy Saturday morning in New York, with a schedule packed with bilateral meetings, Eliasson relaxes in his Manhattan apartment during a break from annual General Assembly preparations. Eliasson, 73, a veteran diplomat and former Swedish minister of foreign affairs, moved into the top-floor two-bedroom flat, with its sweeping views over New York’s east side, when he took up the number-two post at the UN in July last year. “It’s a rental,” he says, “[and] after a year and three months, I think I’ve succeeded in making it home.”

The son of a factory worker-turned-union leader from Gothenburg, Eliasson was the first member of his family to graduate from high school. “My father had seven years of school. My mother four. My father was a metal worker in SKS, the ballbearing factory,” says Eliasson. A married father of three, he keeps a collection of framed photographs of his family, including his parents and seven grandchildren, on a table in the dining area.

Eliasson’s working class background, he says, has been a benefit in a long career that includes ambassadorships to the UN and the US. “I consider it a gift to have that background in my present job . . . In order to do this job right, you need to be connected to realities on the ground.”

Eliasson’s first brush with the grim realities of regional conflict came as a negotiator in the Iran-Iraq war of 1980-1988. “I was assistant to [Swedish prime minister] Olof Palme, who was UN negotiator. I took over the job after he died [Palme was assassinated in 1986],” says Eliasson who adds that the experience was humbling. Did his stint coincide with Saddam Hussein’s use of chemical weapons? “They started using chemical weapons around ’83, ’84. Some attempts were made to stop it – rather weak attempts, I must say,” says Eliasson.

Now, with some countries mounting a diplomatic response to the UN verified chemical weapons attacks in Syria, the UN is taking a lead in negotiations. “We’re got experts working on this. We’ve started the process.”

Taking pride of place in the flat are two striking portraits. “This is Dag Hammarskjöld,” says Eliasson, pointing to a sketch-like portrait of the Swedish UN secretary-general who died in a 1961 plane crash. “He died on my 21st birthday. I was in the navy when I got the news.” The portrait is on loan from “two New York ladies. They deposited it in my apartment. Their father commissioned it.” And hanging near the dining area is a portrait of a pensive Raoul Wallenberg, the Swedish diplomat credited with saving up to 100,000 Hungarian Jews. “The fascinating part is that the background is the railroad map of Hungary with tracks that took the Jews to camps from Budapest,” says Eliasson. “Peter Malkin, the artist, was Israeli.”

The portraits on his wall, he says, are daily reminders of the costs of global inaction. Eliasson has faced frustration over refugee crises before: between 1992 and 1994, he was the first UN undersecretary-general for humanitarian affairs. “The first big challenge we had was Somalia, ’92-’93 . . . Now with Syria, it’s critical to pitch in,” he says. “It’s very sad that we have less than half of what we need. Pledges are 43 to 47 per cent. Both the UN and its refugee agency need more resources to do the job. About 4.25m Syrians are also displaced inside the country.”

Despite the gravity of the current crisis, Eliasson says he enjoys the lighter sides of living in New York. “There is a wonderful local market. You get fresh fruit, fresh vegetables, fresh apple cider. They put up booths from New Jersey. I love the scents,” says Eliasson, who often starts staff meetings with reports on market finds. But his workload, he says, precludes hosting dinners at home.

“I entertain at the UN headquarters. I try not to go out on weekdays. There’s too much to read and prepare.” He does, however, miss the presence of a piano. “Kerstin is a wonderful pianist,” he says, of his wife of 45 years, a former Swedish state secretary of education, who travels between New York and Stockholm. “When I sit and work, it’s great to listen to Chopin and Mozart.”

Eliasson agrees that the UN’s role in the Syrian crisis has put it back into the public eye. But can he answer criticism that the UN will always be weakened by the power of a few countries to wield Security Council vetoes? “That’s the structure we have to live with . . . It will be as strong as the member states want it to be,” he says. “If the UN didn’t exist, something similar would take its place.”

To sceptics, including many members of the US Congress, Eliasson issues an invitation. “I would welcome you to the field. Come to the field and see what we are doing.” Development, he says, is a large chunk of it. “There is no peace without development. No development without peace.” The UN, he says, plays a vital role in managing human experience. He ticks off a few institutions under its umbrella: “The UNDP, the ILO, the World Food Programme, the World Health Organisation, Unicef.”

Time is running short and Eliasson finishes off the last of his coffee as he prepares to rush off to greet heads of state from the UN’s 193-member countries swarming into New York. “The secretary-general has about 20 meetings. I have 10. That’s when the science of cloning isn’t advanced enough. We call it the crazy week.”

Still, he points out that the venue offers valuable chance encounters for countries “that don’t talk to each other”. Does this include chats in the lift with Iranian president, Hassan Rouhani? “There are positive signals,” says Eliasson, referring to fresh overtures from Iran over the fate of its nuclear facilities. “We hope we’ll be able to solve these nuclear issues through dialogue and negotiation.”

Eliasson ends the interview with an appreciative glance at the view from his window. “I can see the sun rise and I can see it set from here. It’s reflected on the other buildings,” says Eliasson, who also points to the irony of granting an “At Home” interview at a time when millions of Syrians displaced by war will no longer have homes. “The winter is hard,” he says. “The mountains are high. Half are children. They’ve been forced to leave their homes.”

——————————————-

Favourite things

Magnifying Glasses:

“I happen to collect magnifying glasses,” says Eliasson. “I have quite a collection. I brought a few of them to New York. Friends bring them to me from England, from China.” Eliasson began his collection in the 1980s. “When my father’s eyesight was deteriorating, he got out his magnifying glass. I thought I’d better be prepared, but collecting them turned out to be a hobby. They are beautiful.”

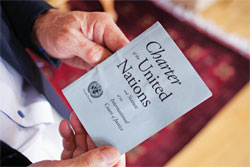

UN Charter:

“I always have it in my pocket,” Eliasson says, reaching into his coat pocket to produce a tattered blue booklet. “I consult it often. You need to always remember the principles and values; and the person out in the field. That’s the mission. I think I’m equally energised by the charter as I am by the mission.” Eliasson’s priority to do list, as part of the UN’s Millennium Development Goals, includes getting clean water and plumbing to every city and village in the world. “That would be a real start,” he says.

Comments