What is good design? A look at the many definitions of quality

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Good design,” once said Dieter Rams, “is as little design as possible.” Easy. Problem solved.

The German designer’s work for Braun stripped away the superfluous and brought Bauhaus ideas into the media age. It ultimately inspired the iPhone — a smooth, enigmatic tablet that appeared in our hands like the black monolith appeared to the apes in Standley Kubrick’s film 2001: A Space Odyssey. Suddenly we understood what good design was. Rams had been right. Or had he?

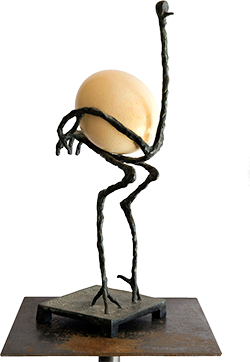

According to design think-tank DeTnk’s round-up of the best-selling designs at auction, Diego Giacometti (younger brother of Alberto Giacometti whose “Pointing Man” became the world’s most expensive modern sculpture when it sold in 2015 for $141m) is the world’s most successful designer by auction sales. Yet his work hardly satisfies Rams’ criteria. Does that make it bad design? Or does it make it art? Is it, in fact, design at all?

“Good design,” Rams also wrote, “makes a product useful.” Well, useful if you need to display an ostrich egg in an armature that looks like the Road Runner burnt to a crisp by a nuclear bomb.

How about fashion? If a revered shoe designer makes shoes that hurt women’s feet, is that good design? Or how about all that design engineering finesse put into the latest Maserati or Ferrari? These are desirable cars, the global aspirational symbols of feckless young males and mid-life crises. Yet what does all that design achieve? Speed and acceleration impossible to exploit on the road? Massive fuel consumption? Insurance nightmares? Or how about the clunky watches with overly complex faces and diamond-studded bezels that inhabit the pages of magazines? This is design as desire, the production of stuff geared to conspicuous consumption and to displaying the wealth and taste (or otherwise) of the owner and flaunter.

Thorstein Veblen, the US economist, identified this urge to consume conspicuously more than a century ago and it still defines an entire industry of status production. Yet design today is much, much more than products.

“Design,” said Steve Jobs, “is a funny word. Some people think design means how it looks. But, of course, if you dig deeper, it’s how it really works.” The great guru of Apple’s desirable tech hit on something big. Design is not necessarily about the product — it is about the experience. It is something much bigger than the thing we think we are buying. It is about how something feels and makes us feel. That explains the Maseratis and the Rolexes, the stilettos and the iPhones. Design has become a victim of its own success.

We are living in an intriguing moment. The recent triumph of young architects’ collective Assemble in the Turner Prize, Britain’s foremost contemporary art award, revealed that art is imploding. Embarrassed by its own uselessness and its inability to enact social change, the art world turns to the agency inherent in architecture. The same could be said of the phenomenal success of Chicago artist Theaster Gates who has brilliantly harnessed the wealth in the art industry to seed social projects. For more than a decade now designers have been going in the opposite direction. Envious of the money and glamour accorded to even the most incompetent and banal artists, designers think to themselves that they could have a bit of that. So they have looked to the galleries to find a more lucrative outlet, one that recognises them as the stars they think they are. Sometimes referred to as “design art”, this is a hybrid territory where the usual rules do not apply. This is art made for display in the gallery, the auction house and the interiors of prime real estate. How do you judge Atelier Van Lieshout’s chair in the shape of a skull designed for sensory deprivation? Or Studio Job’s Robber Baron furniture against Rams’ criteria? It is impossible, quite deliberately. This arm of design has deserted the functional for the psychological, choosing instead to address the needs of the intellect rather than everyday life.

Then there is social design. To understand the ideas behind this we need to look back to designer Victor Papanek. “There are professions more harmful than industrial design,” said Papanek, “but only very few of them.” Social design emerged from the idea that designers were complicit in a destructive cycle of consumption and waste. It embodies the notion that design can be applied to social processes and human wellbeing, an escape from the object into the world of human interaction. But, again, it defies Rams’ descriptions of what design can be. Then there is critical design. This is the idea that the brief could be a future scenario in which speculation about possible futures can frame a debate about the consequences of what we do today. It is using design as a tool to attempt to understand the problems we are facing and the decisions we make.

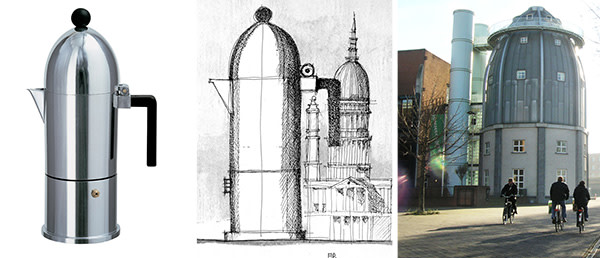

In these cases, design is intended as a provocation or a manifestation of a social good. We need to understand that design is on a particular trajectory. What we now think of as design was, in an older age, known as “the applied arts”. It was effectively the decoration of an object. The modernists turned this notion on its head. For them, design was not decoration — ie the application of craft to an existing form — but rather the stripping of that object to its essence. For the Bauhaus designers — the tradition from which Rams emerged — design was the opposite of an applied art. It was a subtractive philosophy in which the “thingness” of the product would be exposed by making it naked and revealing its underlying structure and function. So a good design passes from something that is exquisitely and tastefully decorated (what is important here is who judges taste) to the more absolute judgment of a product that is legible in its construction and its function (whether it works). Then, along with pop and the postmodern, things changed again. Now designers attempted to express something beyond the function, something about consumption or culture. Think of Aldo Rossi’s coffee sets that resemble the archetypes of a city — an underemployed architect designing tableware as dream metropolis.

Designers now seek to transcend the object itself to use their discipline as a mechanism to critique society as well as the consumption-capitalism on which their profession theoretically depends. At a loss to explain exactly what it is they do for their clients, designers demote themselves to “storytellers”, weaving spurious narratives around vacuous storyboards for rebrands, interiors and product launches. Designers are commissioned to create a brand narrative to post-rationalise a product. From coffee to trainers, the story is everything — the artisans, the sourcing, the packaging is all part of the story, which has itself been designed. “Narrative” replaces meaning and becomes the vehicle through which they express the absence of ideas and the existential scream of contemporary consumption. If we return to Rams, he also said: “Good design is making something intelligible and memorable.” Yet he added: “Great design is making something memorable and meaningful.”

That quality in design still resides in its ability to convey meaning. Thus, ironically, something like Rolf Sachs’ uselessly floppy felt chairs or Dunne and Raby’s Ethiculator (a calculator for resolving everyday ethical dilemmas) might be able to embody more about our age than the most successfully designed high-tech product.

Design is almost always conceived of as a solution and designers as problem solvers. But sometimes the real interest lies in the problem, not the answer. Perhaps we could conceive of design not as a product but as an idea. Which is where Giacometti’s ostrich comes back into the story. In Rams’ terms, this thing is about the chicken and the egg. Giacommetti’s frazzled bird is memorable because it poses mankind’s ultimate question, even though it doesn’t address a functional problem.

You might think good design is an easy thing to judge. It certainly was for Rams. A product either worked or it did not. It either sold or it did not. It either became a collectable classic (usually in the case of it not actually working) or it did not. No more. Now design is as fluid and free-floating as art. It might be exactly the liberation design needs, or it might provoke the same crisis being suffered by artists who realise they are trapped in a cycle of collecting, consumption and investment, a world governed by the super-wealthy in which meaning defers to money.

Ironically, it was design that was once inseparable from capital, the manifestation of production and desire. Perhaps design will be able to use its more legible language to build on memory and meaning and exert a real impact in a way that art has seemed unable to. Or perhaps it will infuse so fully every aspect of our culture that it becomes virtually invisible. As little design as possible? I doubt it.

Edwin Heathcote is the FT’s architecture and design critic

Photographs: Atelier Van Lieshout; Eddie Linssen/Alamy; Getty Images

Comments