Surging price of battery materials complicates carmakers’ electric plans

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The car industry’s multibillion-dollar bet on electric vehicles was built on a single premise: that batteries would carry on getting cheaper.

In 2019, Volkswagen executives even brandished charts predicting a steady decline in battery costs, as they laid out their ambition to consign the combustion engine to history.

For years the industry was proved right: battery costs fell from $1,000 per KWH for the first models more than a decade ago to about $130 in 2021, paving the way to making them affordable for middle income families.

But Russia’s invasion of Ukraine threatens to halt the slide.

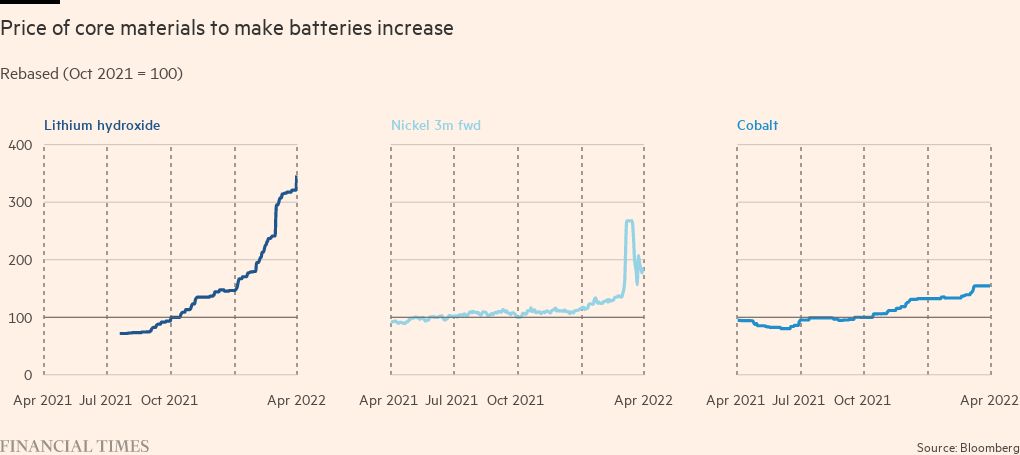

Prices of nickel, lithium and cobalt — key raw materials for battery manufacturing — were already rising because of global demand. But with Russia accounting for 11 per cent of the world’s nickel, and supply chains already stretched, the war has sent the cost of such commodities skyrocketing.

The price of these three metals required in a 60KWh battery, enough for a large family sport utility vehicle, has risen from $1,395 a year ago to more than $7,400 in early March, according to battery group Farasis Energy.

Battery companies, carmakers and suppliers are now grappling with the prospect that electric cars may be less profitable, or require cheaper materials, if they are to remain financially competitive.

“At the moment the raw material prices are a burden for our target to reduce battery costs,” said Audi chief financial officer Jürgen Rittersberger, whose brand has pledged to launch battery-only electric cars from 2026.

However, neither Rittersberger nor most of his fellow European car executives are yet raising the alarm about the impact of rising prices on the rollout of electric cars.

For a start, battery material prices are not rising in isolation — costs of aluminium, steel and copper that are also used in engine-powered models have risen since the invasion, too.

“We have to bear in mind that we need specific materials for batteries . . . but we also need, for example, rhodium, palladium and platinum for the [catalytic] converters in our [combustion engine] cars, so we have to expect that the cost in both cars will increase,” said Volkswagen’s chief financial officer Arno Antlitz.

BMW sustainability boss Thomas Becker said the Munich-based carmaker was also not concerned. “We have long term supply contracts with all battery cell suppliers. So I wouldn’t say that there was any imminent effect on the structure of supply,” he said.

“It would be premature to make any predictions about a longer lasting and structured impact on our supply chains at this point.”

In addition, the prospect of electric vehicle price rises comes as demand has surged for battery-powered cars, helped by the big increase in the cost of petrol.

More than 1.1mn battery-driven cars were sold in the first two months of the year, according to figures by Bernstein, an almost 90 per cent rise on the same period last year.

Interest has risen even faster since the invasion of Ukraine, as higher fuel prices increase consumer concerns about running costs.

“Demand [for EVs] has been staggering over the past few weeks,” said Kia’s UK boss Paul Philpot.

AutoTrader, the largest British online marketplace for cars, found that almost a quarter of searches in March were for electric cars, up from 15 per cent a month earlier.

The company’s commercial director Ian Plummer said fuel prices are consistently “the single biggest driver of consumer interest in EVs”.

But in the longer term, electric car prices may still rise, as battery material costs account for about a third of the EV vehicle prices paid by motorists, according to industry estimates.

Chang Jung-hoon, an analyst at Samsung Securities, calculated that a 10 per cent rise in nickel prices will lead to a 2.4 per cent rise in the cathode price. If the spot nickel price of $42,995 on March 7 translates directly into battery prices, the cathode will rise by 26 per cent and the price of the whole battery by 6 per cent.

Much depends on whether higher raw material prices feed into batteries and cars and, eventually, on to consumers.

SK On, one of the world’s largest producers of high-nickel batteries, is “actively hedging against price fluctuations of those metals but surging prices will definitely have a negative impact on our profitability,” head of procurement YJ Kim said.

LG Chem, another battery maker, said: “If the uncertainty continues in the long term, it will have a negative impact on the battery and EV industry as a whole, so we are closely watching the situation.”

Negotiations between carmakers and suppliers, notoriously robust at the best of times, will be key in determining who shoulders the higher prices.

Vitesco, a German auto supplier that makes powertrains, is assuming it can pass through about 80 per cent of higher costs on to manufacturers, finance officer Werner Volz said.

Analysts say manufacturers’ recent enthusiasm for battery cars may even wane as they realise they cannot make as much money from them as previously expected.

“Automakers are likely to shift to premium gasoline cars for higher profitability as their EV profitability is likely to get worse,” predicted Kim Young-woo, an analyst at SK Securities.

“So higher prices of nickel and other metals are likely to fuel concerns for both EV and battery makers because higher prices would dampen consumers’ appetite for EVs.”

VW still predicts its mass market rollout, as well as its collaboration with Ford, will help the company rein in electric vehicle costs.

Andy Palmer, chief executive of Hindujah-backed electric busmaker Switch Mobility who oversaw Nissan’s launch of the electric Leaf car in 2010, says the long-term trajectory of battery prices still heads downwards.

“Over time, I think we’ll continue to see some fall in the cost of batteries through technology change and economies of scale,” he said.

“When we started the production of Nissan Leaf, we were paying about $1,000 per kilowatt hour,” he added. “The price now is about a hundred dollars per kilowatt hour. So over time, you’re definitely seeing a reduction in the price of batteries, and that’s obviously driven by demand and supply.”

Even if prices do rise, sales of electric cars have a momentum that makes them almost unstoppable.

“EVs and batteries are related to the industry trend of regulating carbon emissions,” said Kim at SK On. “They cannot be simply approached from a profitability perspective.”

“Nickel’s price surge can have an impact on EV demand, but it is far-fetched to assume that EV demand will fall.”

Twice weekly newsletter

Energy is the world’s indispensable business and Energy Source is its newsletter. Every Tuesday and Thursday, direct to your inbox, Energy Source brings you essential news, forward-thinking analysis and insider intelligence. Sign up here.

Comments