US power line tensions grow over green energy surge

Simply sign up to the Utilities myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

The battle over a power line in Maine features a television advertisement depicting felled pine trees in the wooded US state paired with noir images of a corporate tower in modern Bilbao, near the Guggenheim art museum. A voiceover declares: “A good deal for Spain, and a bad deal for Maine.”

The Spanish utility company Iberdrola’s political action committee has spent almost $15m to promote its $950m New England Clean Energy Connect electric transmission project which would run for more than 230km. Yet last month opponents won a partial stay of construction in court and an activist group filed papers to hold a state referendum to revoke its permits.

Stringing the land with ugly wires has always sparked pushback. This time the fight includes hefty corporate rivals that stand to lose a share of the market. And the stakes are rising as electricity emerges as the quickest way to strip carbon from the energy system in an effort to stem climate change.

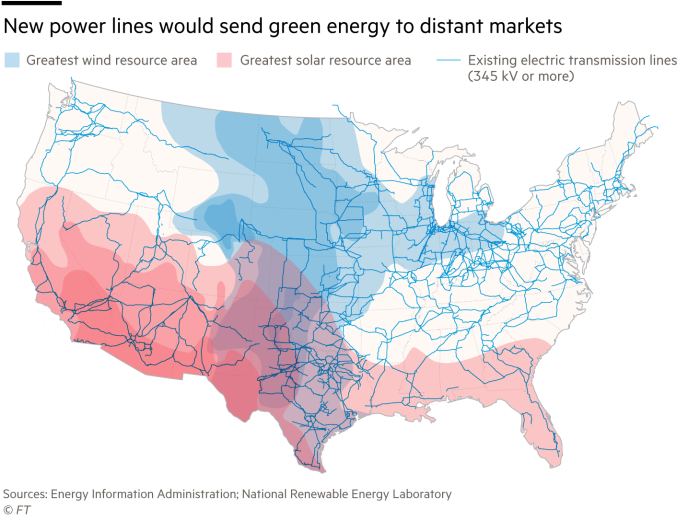

Since most green power is built in remote areas, new, long-distance transmission lines must deliver it to customers, advocates say.

The issue was put into stark relief this week as the frozen citizens of Texas suffered dramatic blackouts exacerbated by a lack of connection to outside regions — an intentional design that exempts the state’s grid from most federal regulation.

President Joe Biden has called for accelerating transmission projects in his executive order on climate in the first week of his administration. Since then, a coalition of 45 energy and environmental groups has pressed the need for a federal tax credit for high-voltage transmission.

Rich Glick, the new chairman of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, wants his agency to reassess policy to trigger more transmission investment. “We have to substantially build out the grid more than we’ve been doing,” he said.

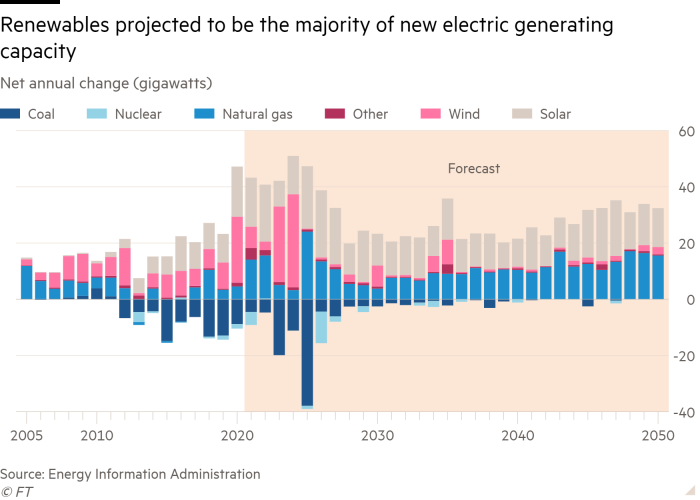

A bigger grid would allow wider deployment of solar and wind power, filling gaps when the sun shines or wind blows in one place but not another. It would also support rising demand from electric vehicles and building heaters.

A Princeton University study estimates the US would need a transmission system that is 60 per cent larger by the end of the decade and possibly three times as large to achieve a net zero carbon emissions goal by 2050.

“We need all the wind and solar we can get. But we also need a significant amount of transmission,” said Jay Rhame, chief executive of Reaves Asset Management, a $3bn fund manager that invests in energy infrastructure.

The buildout would require spending $3bn to $7bn a year to 2030, and another $7bn to $25bn a year in the following 20 years — on top of $15bn a year in past transmission investment, according to a Brattle Group study for Wires, a trade group.

Three major obstacles stand in the way: permitting, planning and deciding who pays for the lines, experts say. Each has been formidable.

Clearing a path for linear infrastructure — such as highways, oil pipelines or electric transmission — always encounters resistance. The fight over permitting the Maine power line shows how fearsome that resistance can be.

An Iberdrola subsidiary in the US, called Avangrid, launched the NECEC project in 2018 to carry 1.2 gigawatts of hydropower — enough to supply more than 1m households — from dams in Quebec. Utility customers in Massachusetts will fund the cost under that state’s policy to drive down emissions.

The project has splintered environmentalists. It was endorsed by the Conservation Law Foundation and Union of Concerned Scientists, who cited the clean energy that would flow into New England.

But the Sierra Club, the Appalachian Mountain Club and the Natural Resources Council of Maine sued to block the line and last month won the court stay of tree-cutting on a 53-mile segment.

They are not the only opponents. The political action committee challenging Iberdrola’s Spanish roots on TV, called Mainers for Local Power, was bankrolled by merchant generators that stand to lose sales in New England’s power market.

These power generators include the Florida-based NextEra Energy, which has become a Wall Street darling thanks to its premier solar and wind development business. NextEra also owns an oil-fuelled unit in Maine and a nuclear plant in New Hampshire. Another opponent is Texas-based Vistra, which has seven gas-fuelled power plants in the region.

“They chose a very xenophobic message that I find incredibly troubling,” said Thorn Dickinson, chief executive of the Avangrid company building the Maine project.

Vistra’s chief executive, Curt Morgan, dismissed the project’s greenhouse gas benefits, arguing that Quebec will replace its exported hydropower with fossil fuel generation. (Dickinson countered that Quebec has surplus power and currently allows water to spill over its dams.)

Morgan added: “It will have an adverse impact on power generation that is existing in New England. Billions of dollars of money spent to serve New England by companies that have invested in it. And through the stroke of a pen, we bring in Canadian hydro to compete.”

Rather than build new transmission lines, it would sometimes be more efficient to place clean resources along existing lines, Morgan said. Vistra recently installed a giant battery on the site of a shuttered California power plant that absorbs surplus midday solar generation and discharges it when needed.

“Repurposing some of the old coal and oil and gas unit sites that have connections to transmission is a far better use of capital than to build new transmission,” Morgan said.

NextEra did not return messages seeking comment.

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here

Massachusetts signed up for Avangrid’s line after another one failed. The local utility Eversource had first proposed to bring in Canadian hydropower through New Hampshire, but the state’s government killed the so-called Northern Pass project.

The Maine and New Hampshire experiences show why expectations are modest for the Biden administration’s transmission goals. US states, like Texas, can veto transmission lines that cross their borders — unlike natural gas pipelines, in which the permitting authority of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission reigns supreme.

Some lawyers believe that the federal government could skirt state barriers. For example, the US energy department has the legal authority to designate special transmission corridors that would transfer permitting to Ferc if a state balked at good projects, according to a study published by Columbia and New York universities.

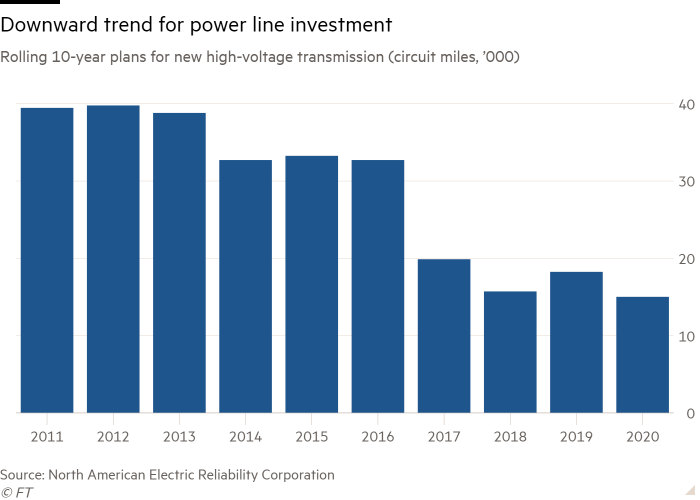

Ferc last updated transmission policy in 2011 to require more planning at a more regional scale, among other provisions. But the policy failed to unleash much investment. In fact, the trend has been downwards.

In 2012 almost 40,000 circuit miles of high voltage transmission was planned for the coming 10 years. Yet the latest projections are far less than what is needed at 15,000 circuit miles, according to the North American Electric Reliability Corporation. Most projects are less than 50 miles long — not lengths that would get wind power from the Great Plains to a big city.

“We know that it takes a long time to plan, site and build transmission. If we’re going to get the country off fossil fuels, we’re going to have to figure out how to do that faster,” said David Hutchens, chief executive of Fortis, which owns ITC, the largest transmission-only electric utility in the US.

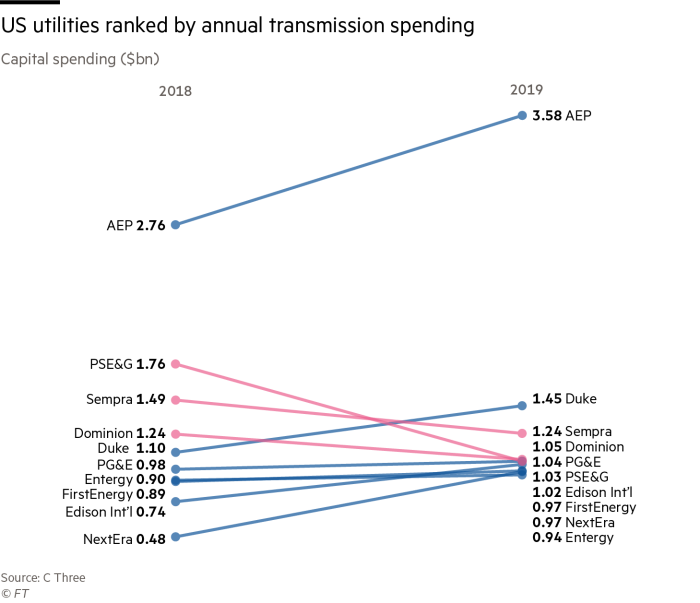

Most interstate lines are owned by utilities, which earn returns on equity of about 10 per cent under rates regulated by Ferc, according to C Three Group, an infrastructure research firm. Parcelling out the costs of transmission across different states and customers has been a roadblock for new projects.

Some power companies and infrastructure investors are still pursuing the opportunity. Even as it attacks Iberdrola’s Maine line, NextEra is in the process of closing a $660m deal to buy GridLiance, which owns 700 miles of transmission lines in six states including sun-drenched Nevada and wind-heavy Oklahoma.

“If we’re going to decarbonise the electric sector, we need to make significant investments in the transmission system. And so I see it as a very high-growth sector,” Jim Robo, NextEra’s chief executive, told investors on announcing the deal.

But progress is slow. Pattern Energy’s Southern Cross transmission project was designed to carry 2GW of wind power from Texas to the south-east. The two-way lines could also have imported power when Texas needed it.

Ferc approved the line in 2014. Seven years later, it remains unbuilt.

Twice weekly newsletter

Energy is the world’s indispensable business and Energy Source is its newsletter. Every Tuesday and Thursday, direct to your inbox, Energy Source brings you essential news, forward-thinking analysis and insider intelligence. Sign up here.

Comments