Should zombie companies be feared?

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Many investors fret that a corporate “zombiepocalypse” may be one of the thorniest problems the global economy faces in the coming years. But a bombshell paper by the New York Federal Reserve argues that this fear may be overdone.

Even before the eruption of coronavirus, concerns that a growing horde of walking-dead companies — usually defined as those unable to cover debt-servicing costs from long-run profits — were pervasive.

Two years ago, the Bank for International Settlements calculated that the share of zombie companies across the 14 big economies it studied had climbed from 2 per cent in the late 1980s to 12 per cent by 2016. The driver was that they stayed undead for longer than in the past, neither recovering nor dying out. The most likely reasons for this were the falls in interest rates that reduced debt repayments and banks being reluctant to pull the plug.

The trend was no accident. In fact, after the 2008 financial crisis, policymakers considered low rates and forbearance absolutely necessary to prevent a mass corporate extinction event that would have caused many more millions of jobs to disappear. In this, the authorities had learnt from the mistakes of history.

Back in 1929, Treasury secretary Andrew Mellon advocated the mass liquidation of struggling companies to “purge the rottenness out of the system”. Foreshadowing Joseph Schumpeter’s theory of “creative destruction”, he argued this would be the best way to ensure a recovery. Instead, the Mellon Doctrine helped turn the crash of 1929 into the Depression.

Nonetheless, many economists worry that allowing feeble companies to shamble on indefinitely does entail real, longer-term economic costs. The 2018 BIS paper estimated that “zombie companies” are unproductive, invest less and suck up resources that could otherwise be redeployed in more dynamic areas. Even beyond the zombie company phenomenon, economists fretted that rising corporate indebtedness in general stunts the ability of companies to invest.

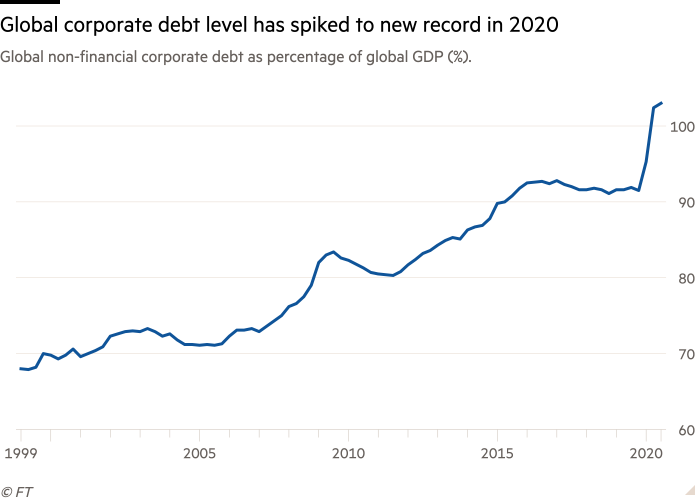

These fears have been supercharged in the wake of the coronavirus crisis. Of the many legacies the pandemic will leave in its wake, a monstrous corporate debt burden is one of the biggest.

The rise in corporate bankruptcies has so far been surprisingly modest, thanks to the extraordinarily aggressive response from governments and central banks, with the latter alone pumping more than $7tn of stimulus into bond markets, according to the IMF.

But the net result has been that the developed world’s corporate debt burden has climbed from an already record 91 per cent of gross domestic product in 2019 to 102 per cent at the end of September 2020, according to the Institute of International Finance. Although rock-bottom interest rates make this more bearable, economists fret that this debt “overhang” will be a millstone around the neck of the global economy for years to come.

Perhaps not, according to the paper published by the New York Fed this month. Using a database across 17 economies going back to the 19th century, Oscar Jordà, Martin Kornejew, Moritz Schularick and Alan Taylor investigated whether big corporate debt build-ups led to deeper and longer recessions, as is historically the case after booms and busts in household or finance industry debts.

Their conclusion is counterintuitive. “There is no evidence that corporate debt booms result in deeper declines in investment or output, nor that the economy takes longer to recover than at other times,” the paper says. Nor did the economists find any evidence that big corporate debt overhangs made economies more fragile, and prone to less frequent but bigger downturns.

Why is this? The NY Fed paper argues that corporate bankruptcy and restructuring regimes are generally much more efficient than those for individuals. Both company owners and creditors are best served with a swift resolution.

However, when creditors are dispersed and combative, contract enforcement is weak or the legal process cumbersome, it can discourage or delay a speedy restructuring or liquidation. This can nurture more undead companies. “More frictions lead to more under-investment and survival of zombie firms, which can impair aggregate productivity growth and slow down the recovery after recessions,” the economists note.

In other words, policymakers should worry less about low interest rates allowing the number of companies to linger in the twilight zone of survival. Instead, they should focus on ensuring that bankruptcies and restructurings are handled as quickly and efficiently as possible.

Comments