The shocking coronavirus study that rocked the UK and US

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

An Imperial College coronavirus model has had a profound impact on public policy since its results were shared with British and American officials last week.

No study has so exhaustively detailed the transmission of the virus through the UK and US population, the overwhelming pressure it has placed on health systems, or the limited effectiveness of individual measures to check its progress.

Like any simulation, it rests on uncertain assumptions. Many factors remain unknown to the research team led by Professor Neil Ferguson, who this week fell ill with coronavirus symptoms. But even with this caveat the conclusions are brutally stark: democratic politicians face only terrible choices in the battle to save lives.

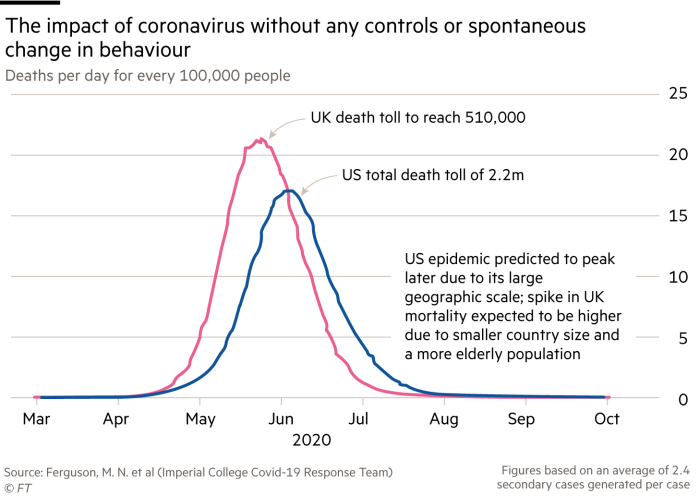

The starting point for analysis is an unchecked epidemic. This would infect eight out of 10 people, according to the researchers, with 510,000 deaths in the UK and 2.2m in the US.

While the estimate draws on hospitalisation rates in Italy, it assumes every patient receives adequate care. In practice the researchers find available beds for critical patients would actually be exceeded by the second week of April. At peak, for every 30 patients requiring critical care, just one could be treated adequately.

The mortality peak would occur after about three months. Because of its geographic size and younger population, the US lags the UK in how rapidly the virus spreads and the rate of death it causes.

While a vaccine is developed — a process that can take up to 18 months — or antiviral drugs identified, US and UK governments are left with two extraordinary choices.

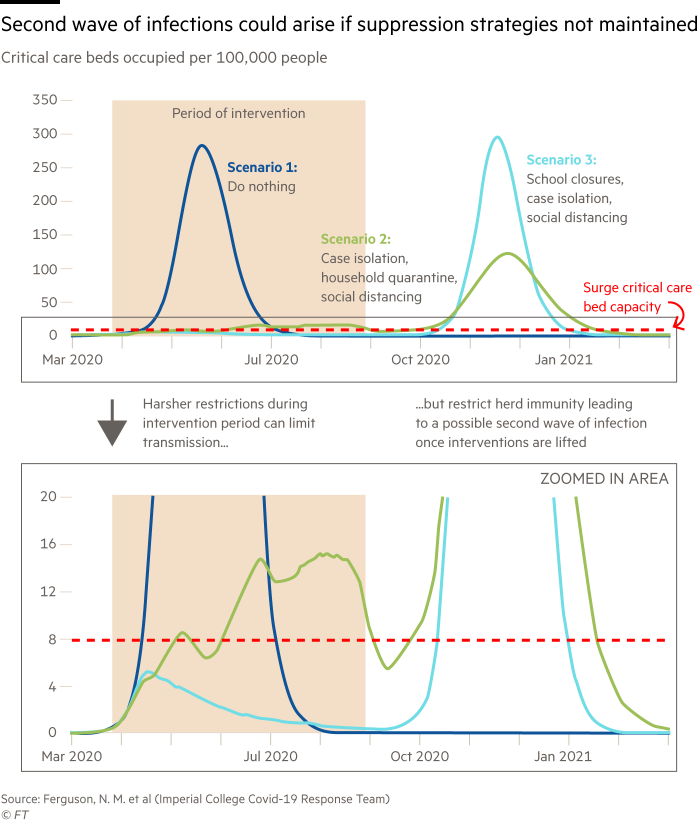

The first is a “mitigation strategy” to reduce the peak of infection while the population builds immunity; the second a more drastic “suppression” approach to quell the epidemic, whatever the cost to the economy, or trauma for social life.

Britain and America started with mitigation measures. But the limits of what can be achieved — even with a combination of stringent measures — are laid bare by the data.

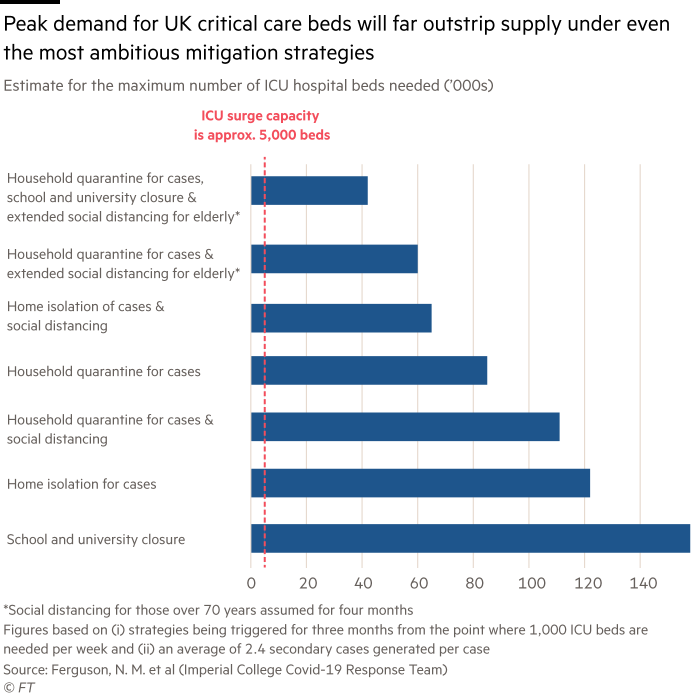

The most effective mix tested involves asking people to stay home for a week if they show symptoms, quarantining their household, and urging over-70s to keep a distance from others.

This would reduce demand for critical beds by two-thirds and halve the number of deaths during the three month period when the measures are applied. Parts of the population would build immunity, eventually driving transmission rates down.

But, crucially, demand for critical beds would still outstrip capacity eight times over in both the US and the UK. The Imperial researchers describe it as “perhaps our most significant conclusion”.

Governments are racing to expand critical care. Yet even assuming all patients could be treated, the Imperial researchers conclude mitigation strategies alone would leave about 250,000 dead in the UK and around 1.2m in America. Boris Johnson, the UK prime minister, recognised that the ultimate toll would be too much for the country to bear.

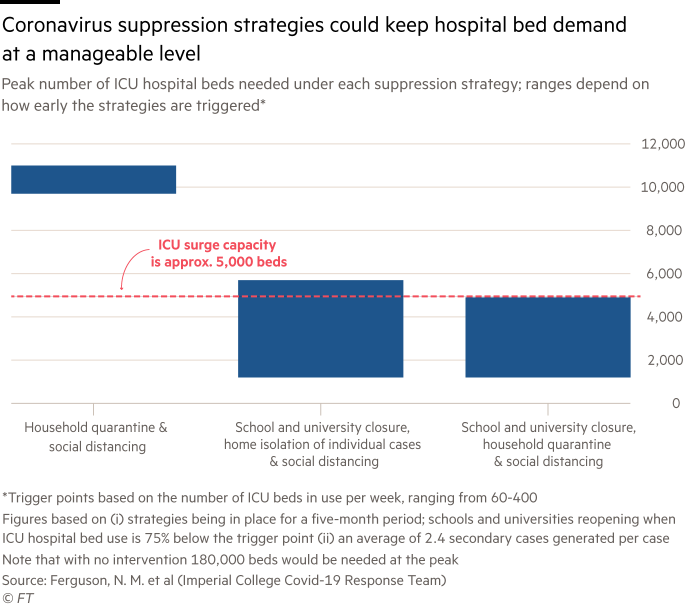

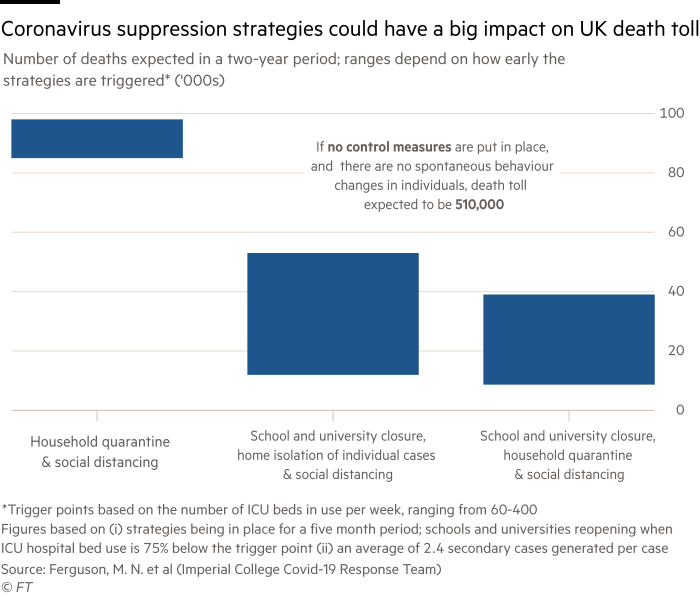

More drastic curbs on society can make a big difference. Short of a complete lockdown on movement, the most effective scenario modelled involves isolating people with symptoms, reducing everyone’s social contact by 75 per cent, quarantining households and closing schools and universities for five months.

If sustained, the measures can choke the epidemic to bring patient numbers to something hospitals could potentially cope with. The study does not, however, quantify related costs: the devastating blow to the economy, consequences for general wellbeing, or mortality rates for other diseases.

This raises the important question of whether — and at what cost — such a curfew could be maintained by any government in the western world.

Without a vaccine, as soon as the toughest restrictions are relaxed, a second wave of infections would be expected to follow.

Contact tracing and intensive testing — as deployed in South Korea — can help extend the effectiveness of measures to stifle infectious spread, as can technology if concerns about civil rights are set aside.

But given available resources in America and Britain, the timescales for vaccines, and the pace of transmission, the researchers conclude suppression is “the only viable strategy” at the moment, while being in no doubt about the profound challenges.

“No public health intervention with such disruptive effects on society has been previously attempted,” the paper concludes.

Additional reporting by Joanna S Kao.

Are you seeing job cuts happen in your workplace or others? Is your company discussing changes in pay or benefits? Tell us what you’re seeing. Send tips and stories to coronavirus@ft.com.

Comments