Europe’s luxury goods capitals reopen to new reality

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

With sales clerks wearing face masks and ubiquitous bottles of hand sanitisers around, the effect of the coronavirus pandemic is impossible to miss at Paris department store Le Bon Marché.

But perhaps the most striking evidence is in a top floor lounge where customers from outside the EU process their sales tax refunds. Before the pandemic, the world’s oldest department store, owned by luxury group LVMH, would have 12 counters open for tourists to reclaim taxes. Last week, the lone clerk on duty said she had handled just three refunds that day.

As the fashion capitals of Paris, Rome and Milan stir back to life, the luxury industry faces a stark reality: Chinese tourists, who accounted for two-thirds of the sector’s sales in Europe before Covid-19, are absent and unlikely to return any time soon.

Now brands such as Chanel, Gucci and Louis Vuitton will have to cater more to their local clientele while also seeking to understand just how deeply the public health emergency has altered customers’ desires and shopping preferences.

Remo Ruffini, chairman and chief executive of Italian luxury brand Moncler, expects the demand shock will spark changes in everything from design to sales tactics. “Normality at the moment remains on the distant horizon,” he told the Financial Times. “When business as usual is not possible, it is the perfect time to reframe a new normal.”

For Moncler, best known for its high-end quilted jackets, it was, he said, “the time to boost digital, to redesign the retail network, to establish a closer and more supportive relationship with the supply chain, to invent new ways to present and sell the collections, and to reconsider how to engage with clients”.

But Mr Ruffini warned that some aspects of the business cannot be changed: “The fashion industry is very physical, we need designers, tailors, fittings, fabrics, not everything can be managed remotely.” To encourage staff back to the office in Milan, Moncler is offering them bicycles, free doctor consultations and Covid-19 antibody tests.

As workers return, an immediate priority will be selling stock, especially of clothing in department stores. Luca Solca, analyst at Bernstein, has predicted “the mother of all end-of-season sales”. At Le Bon Marché, jackets from Isabel Marant and Tod’s loafers were already marked down by 40 per cent.

“Consumers are expecting discounts as a new rule of the game,” said Claudia D’Arpizio, luxury analyst at Bain & Co.

Brands that have their own stores, however, will limit such discounting and use less visible outlet stores to sell down inventory. Some, such as Chanel and Louis Vuitton, have even raised some prices by 5 per cent to 17 per cent to offset higher costs and protect margins.

There are signs that shutdowns have turbocharged online sales of luxury goods, despite misgivings about how to replicate the high-end experience virtually. A survey of 1,000 luxury customers in the US and Europe found that 24 per cent had shopped online for the first time while stores were closed, and 76 per cent said the experience was positive, according to a study by McKinsey for the National Chamber of Italian Fashion and Pitti Immagine, a trade event organiser.

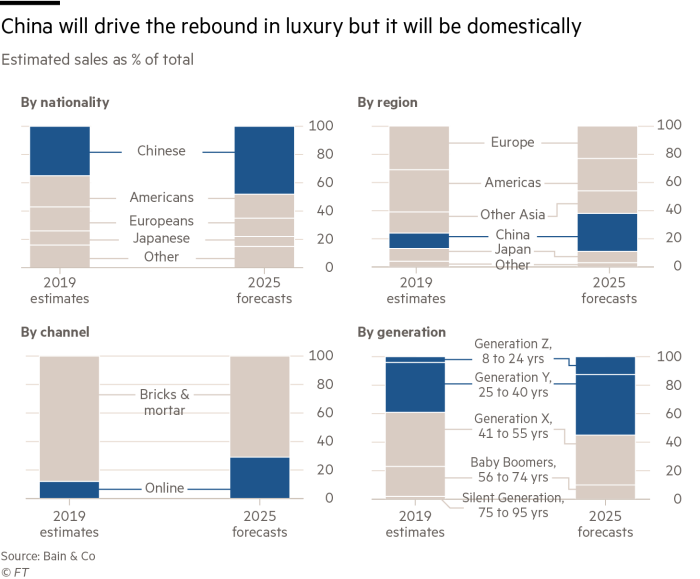

Bain has forecast online sales, which accounted for 12 per cent of luxury sales last year, will reach 28 per cent to 30 per cent of the market by 2025.

London, Paris and Milan are preparing to hold online fashion weeks in June and July to showcase new collections despite travel bans. “The rationale behind the online fashion week [in Milan] is that we must support the supply chain,” said Carlo Capasa, president of the National Chamber of Italian Fashion. “We need to launch a sales campaign to make sure orders come in.”

Italy is home to about 67,000 small manufacturers of leather goods, fabric and cashmere, and Mr Capasa warned that many will go out of business without more government support, putting 100,000 jobs at risk.

As boutiques reopen, Kering, whose largest brand is Gucci, said the initial signs from the first week after lockdown in France were encouraging. “Traffic in stores has been higher than we expected and more customers are buying, which speaks of the strength and loyalty of our local clientele,” said the company.

While Moncler, LVMH and Kering have reported strong demand in China since stores began to reopen there in late March, few in the industry expect a quick recovery. Richemont’s chairman has warned of “grave economic consequences” that could last up to three years.

HSBC has forecast sales to fall 17 per cent this year, while Bain has predicted a decline of 20 per cent to 35 per cent. It will take until 2022 or 2023 to return to €281bn in sales seen last year.

As long as international travel remains restricted, getting more Chinese consumers to buy luxury goods at home will be crucial to any recovery.

On Friday, Burberry said its Chinese sales had bounced back in recent weeks because more consumers were shopping at home rather than overseas.

Ms D’Arpizio said brands would have to tailor more products for China, and continue to narrow the price gap between China and Europe, which has long been a key reason why Chinese often buy when travelling.

Erwan Rambourg, an analyst at HSBC, predicted that the repatriation of sales to China would lead luxury brands to reconsider store locations and sizes as leases expire. “I don’t think you’ll see more stores overall, but there will be fewer in Europe and more in China.”

As the industry navigates the downturn, a group of independent fashion designers led by Dries Van Noten has called for the production calendar to be revamped to align deliveries with the seasons and stop early discounting. In an open letter, they proposed that cold-weather clothes be delivered to stores from August through January, and warm-weather clothes February through July.

Mr Ruffini said brands should not chase sales at any price. “The biggest risk I see today for a company is making choices that can damage brand perception in an effort to anxiously recover revenues,” he said. “Not me. Not Moncler. I am not willing to make a long-term vision hostage to a short-term mindset.”

Comments