Media companies worried as ad blocking goes mobile

Simply sign up to the US & Canadian companies myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

An “unethical, immoral, mendacious coven of techie wannabes” — that is how Randall Rothenberg, president of the Interactive Advertising Bureau, describes ad-blocking companies.

In a speech to his members, which include Google and Yahoo, Mr Rothenberg last month described Adblock Plus, maker of the most popular software for blocking ads, as “an old-fashioned extortion racket, gussied [dressed] up in the flowery but false language of contemporary consumerism”.

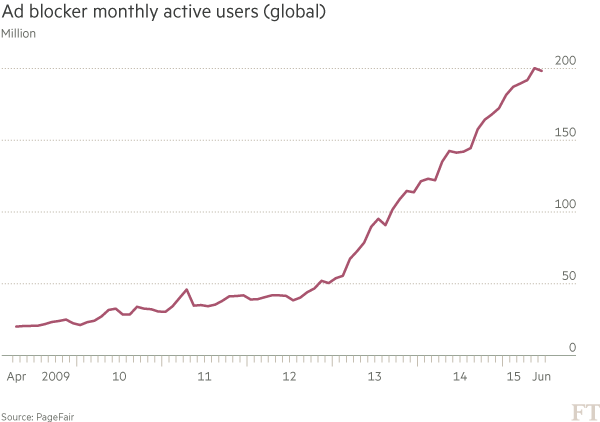

The barbed speech is the latest sign of anxiety in the media and marketing sectors over the rapid adoption by consumers of technologies to prevent advertising from appearing on web pages. More than 200m people worldwide use ad-blocking software, which is double the number two years ago, according to estimates by PageFair, the anti-blocking service, and Adobe, the software company.

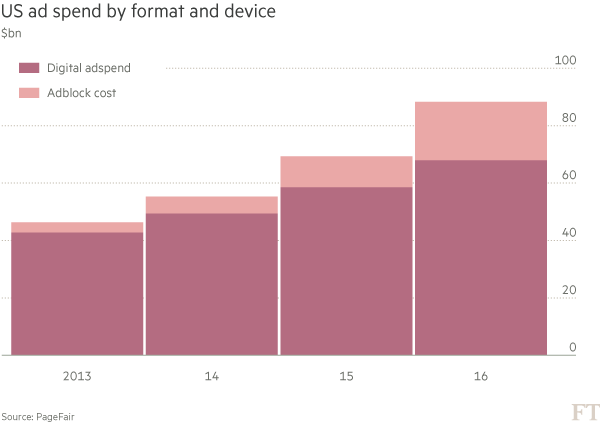

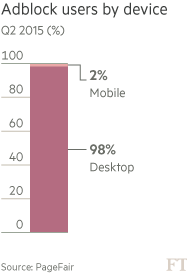

For online publishers whose businesses rely on advertising revenues, the trend is worrying. Their fear has intensified in recent months as blocking technologies, once limited to desktop computers, have spread to mobile devices.

In September, Apple started allowing iPhone users to block ads in its Safari web browser. Apps such as Crystal and Purify soared to the top of Apple’s App Store rankings by downloads, as consumers embraced the option to eliminate ads that slow page loading times, clutter websites, and drain data allowances.

According to a survey by Global Web Index, a research company, 37 per cent of mobile users said they had blocked ads on their device in the last month.

Jason Mander, director of research and insight at Global Web Index, said: “The arrival of ad blocking on mobile has also been encouraging people to adopt this approach across all of their devices.” The survey found that across all ages and genders, at least 70 per cent of respondents said they were either blocking ads already or were interested in doing so.

Mobile network operators have spied an opportunity in consumers’ rejection of ads. Digicel, the Caribbean-focused network owned by Denis O’Brien, Ireland’s richest man, started blocking ads on its network in Jamaica in September. Digicel is working with Shine, an Israeli start-up, whose software prevents companies including Google from delivering ads to mobile browsers and apps.

Mr O’Brien said that the move was “about giving customers the best experience”. But he added that he wanted to force companies such as Google, Yahoo and Facebook “to put their hands in their pockets” and pay Digicel to allow their ads to reach itscustomers.

Advertisers and media companies are angry that ad blocking groups want to take a cut of their business. Many have focused their ire on Eyeo, the company behind Adblock Plus, which accepts payment from companies including Google and Microsoft to allow some ads through its filters.

German media groups including ProSiebenSat.1 and RTL have sued Eyeo, alleging that it is guilty of anti-competitive behaviour. However they have failed to win in court, and Eyeo says its activities are entirely lawful.

The ad blocking trend is “a wake-up call for better advertising”, says Norm Johnston, chief strategy and digital officer at Mindshare, the WPP-owned media agency. “If you don’t pay attention . . . then things will get worse.”

But he says fears about ad blocking are exaggerated. “The vast majority of people want free content,” he argues, and so will ultimately have to accept advertising.

Indeed, an increasing number of media companies, such as ITV and Channel 4, the UK broadcasters, refuse to load content on their websites when they detect that a visitor is using an ad blocker. If you want to watch their shows, you also need to watch their ads.

Forbes, the business news site, also recently began asking readers with ad blocking software to turn it off. The company found that 42 per cent of the 2.1m visitors who were asked to disable their ad blockers did so.

While Digicel has shown that in-app advertising can be blocked at network level, telecoms industry experts say that it would be difficult for US and European mobile operators to follow suit. To protect “net neutrality” — the principle that no internet traffic should be favoured or blocked — regulators in many jurisdictions prevent internet service providers from interfering in the data traffic that passes through their networks.

Comments