What Brexit means for the UK economy

Has being part of the EU been good for the UK economy?

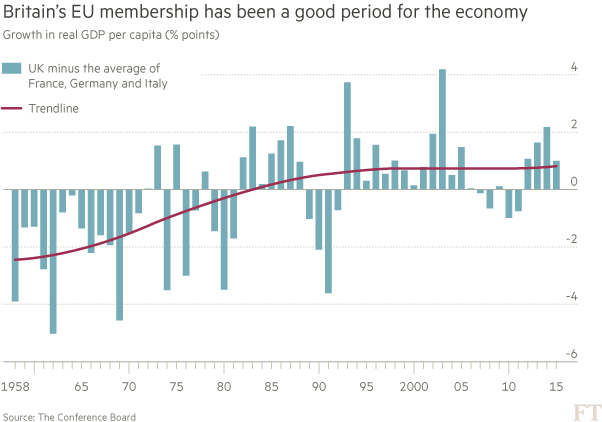

Since Britain joined the European Economic Community (now the EU) in 1973, the nation has become one of Europe’s best-performing large economies.

During that time, domestic product per person has grown faster than Italy, Germany and France, three big economies that the UK had previously lagged behind. In 2013, the country became more prosperous than the average of those economies for the first time since 1965.

Other factors were also at play. The UK had to seek help from the International Monetary Fund in 1976. Margaret Thatcher, the late prime minister, privatised state-owned companies and liberalised the economy in the 1980s.

Still, most economists agree that the EU effect is at least part of the reason why the UK’s relative economic performance has improved over the past four decades.

Why would EU membership help Britain’s economic performance?

Many economists argue that the main contribution the EU has made is to British competitiveness, which increased as the country’s companies fought for markets with rivals across the continent.

Some maintain that greater trade has helped the UK economy all the more because companies that trade internationally have been responsible for most of the country’s increases in productivity. Meanwhile, the UK has become the bloc’s top recipient of foreign direct investment.

Some aspects of membership are not so positive. Apart from a net benefit to the public finances of importing workers, the free movement of people has not itself obviously raised the prosperity of people in Britain.

If the EU has indeed helped Britain open to the world, that openness has not always been an unalloyed advantage either. When the global financial crisis hit, the nation found itself exposed to bad foreign assets held by UK banks.

Can we be specific about the size of the EU effect on the economy?

Prof Nick Crafts of Warwick University says no one can know exactly how much the EU directly benefited Britain but that “a reasonable estimate” is that gross domestic product is 10 per cent higher than it would have been if Britain had never joined. Other economists have put the size of the EU at twice the size or more.

However, Prof Crafts says there is little evidence that joining the bloc has increased the country’s long-term rate of growth. In fact, the boost seems to have principally occurred during two periods: the 1970s, soon after the UK joined, and in the 1990s, after the EU opened its single market in goods.

What about the EU membership bill?

One should be wary of exaggeration. Although the headline figure for the country’s annual transfer to the EU is £18bn, the net cost of membership is £7bn — after taking into account a rebate secured by Thatcher and EU payments to the UK. This translates to about £260 for each British household, not necessarily a big factor for the economy as whole.

Would millions of British jobs go if Britain left?

This also has been the subject of wild claims. For years, pro-EU politicians have bandied about the figure of 3m jobs at risk in the event of a British departure. But this is premised on the idea the UK would catastrophically forfeit access to European markets. No serious economic analysis suggests that all trade with the EU would cease in the event of Brexit.

So what would Brexit mean for the economy?

It is much harder to specify how leaving the EU would affect the British economy than it is to examine the impact of four decades of membership.

Not only is Brexit a future hypothetical event, it also still largely lacks definition. Some EU critics say it would be possible to leave the bloc and scrap free movement of people while retaining access to the single market.

Their opponents say such a suggestion is fanciful in the extreme, adding that a UK outside the EU could either choose to follow Norway, which pays into the EU budget and implements the bloc’s regulations or opt for a much more distant relationship, with trade governed by World Trade Organisation rules.

But it is possible to scrutinise the assumptions and likelihood of three different possible scenarios:

- Booming Britain: Adherents of this scenario say the UK should not yoke its fate to the underperforming eurozone economy and should instead look further afield to more dynamic markets. However, trade deals with all these groups would need to be struck speedily: the EU is by far Britain’s biggest trading partner, and trade deals with another 60 countries would lapse if Britain left the bloc.

- Troubled transition: This scenario is based on the idea that trade is not one of the biggest issues for British economic prosperity and that, as a result, leaving the EU will not fundamentally affect long-term growth. But it does hold that the process of leaving is a risky one, with the possibility of a sharp fall in sterling and a fall in the price of UK assets.

- Disastrous decision: This scenario assumes that Britain ultimately reaches a looser trading relationship with the EU, which makes it more difficult to sell goods and, in particular, services to the continent. Deals with third countries become hard to reach, investments in Britain decline and the economy falls behind the country’s rivals.

Find out more about each of these scenarios and how likely they are to occur here.

What does Martin Wolf think?

The FT’s chief economics commentator is in no hurry at all to leave the EU and thinks complaints of Brussels over-regulation are overblown:

“Analyses by the OECD consistently show that the UK economy is among the least regulated of all its members. The strong performance of the UK’s labour market supports this conclusion . . .

“Nobody can credibly argue that EU membership has been a significant obstacle to UK prosperity. The main obstacles — poor education and low investment, for example — are homegrown. It is conceivable that the EU would become a significant obstacle in future. In that case, the UK should leave. But it is vastly premature to do so now.”

————————-

UK’s EU referendum: full coverage and analysis

View the FT’s comprehensive guide to the vote on whether Britain should stay in Europe, with all the latest news, analysis and commentary from both sides of the debate. See more

————————-

Comments