How Cecil Beaton immortalised the Bright Young Things

Simply sign up to the Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

In the mid-1980s, as the most junior member of the Vogue Library, I had to hand out magazines and newspapers around the five floors of Vogue House, Hanover Square (the sixth floor had been the fabled Vogue Studio – think Bailey and Shrimpton – but was now closed for business). Back then, magazines were sloshing with money; new members of staff were hired at an alarming rate. We couldn’t keep up with their names. We certainly gave up on their hyphens.

Yet there were still some atoms of the past. Beatrix Miller, Vogue’s editor-in-chief, had started out, it was rumoured, as a stenographer at the Nuremberg trials; while over at House & Garden, Robert Harling, in naval intelligence with Ian Fleming, was said to have been the model for James Bond. But it was Harling’s “gardens editor” who struck me the most. Ramrod-straight and clearly once handsome, he was now florid and indifferent. This was Peter Coats (or “Major Coats”, as he reminded me on a near-weekly basis). I would pass him The Times; he would pass me, without looking up, his letters to post. The pile ascended in order of social significance: answers to queries from members of the public at the bottom; then the bank; then the Earl of Snowdon and so on. Often the topmost was simply addressed to one “Lady Lindsay”.

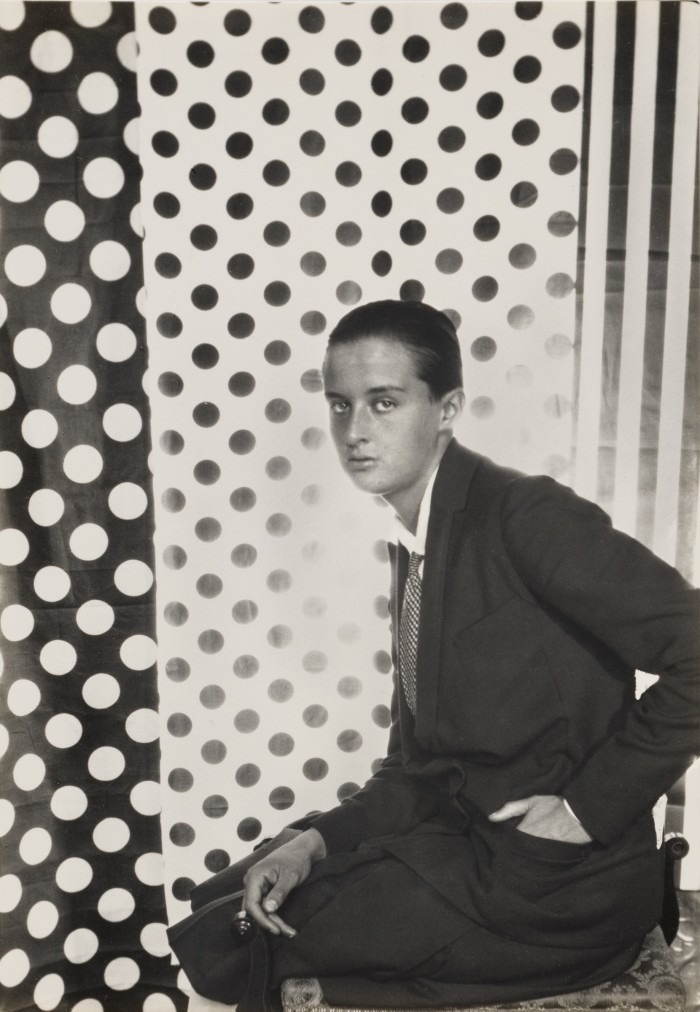

I found out that Lady Lindsay had been, half a century before, Loelia, Duchess of Westminster, married to the fabulously wealthy Hugh “Bendor” Grosvenor, 2nd Duke of Westminster, and the first to be christened the “Brightest of the Bright Young Things” (when she tired of it, the crown passed to her cousin Elizabeth Ponsonby). A photograph of her by Cecil Beaton was kept in Vogue’s archives, dating from 1930, the year of her marriage. If she looked a little uneasy, there were good reasons, not least because the tiara atop her immaculately shingled head was colossal. The Westminster “halo” tiara was fashioned by Lacloche in the oriental “bandeau” style to include the Arcot diamonds, once belonging to Queen Charlotte, consort to George III. “Our most beautiful of duchesses”, sighed Vogue. And, as it would transpire, one of our most unhappy.

Some 36 years after I saw it, that Beaton portrait of Loelia will be on show at the National Portrait Gallery in Cecil Beaton’s Bright Young Things, my survey of Beaton’s early years, the friends (and enemies) who beat a path to his door – actually, his parents’ door at 61 Sussex Gardens, Paddington – to sit for London’s newest star photographer. Conventional society was on its knees, shattered by the Great War, and the young people who crowded into Beaton’s homespun scenarios were not yet aware of what other horrors the future might hold. Instead, they formed close friendships, linking some of the cleverest writers, artists, designers and composers of their generation, as well as those whose significance was not yet apparent.

Beaton felt his progress might be hampered by a lack of funds. His diaries bemoan his impecunious circumstances. “What will I be?” he wailed at one friend. “I wouldn’t bother too much about being anything in particular, just become a friend of the Sitwells, and wait and see what happens,” came the reply. Which, in a short space of time, is exactly what happened. Edith Sitwell became his first significant sitter and patron. And from then on, everyone paid; there were no “complimentary sittings”.

The circles he now began to move in were grand and immensely wealthy. Another patron, the cigar-smoking Viscountess Wimborne, gave parties of such opulence at Wimborne House (now part of The Ritz) that Siegfried Sassoon likened them to “Rome before the fall”. According to Lady Asquith, Alice Wimborne’s yearly dress allowance was a staggering £10,000 (her own a more modest £100).

But Beaton reserved most of his awe for the maharanis of princely Indian states who swooped into London for the season and for the shopping. The extravagance of the Maharani of Cooch Behar was conspicuous, her taste theatrical. Her shoe collection, made for her by Ferragamo, was legendary: diamonds ran up the heels of one pair; phosphorus infused the material of another, so that they glowed in the dark. When Schiaparelli made her a rug, it was out of the hides of 14 leopards shot by her daughter.

Committed Europhile Princess Karam of Kapurthala had married into one of the most extravagant royal houses of the Punjab. The main Kapurthala palace was modelled on Versailles, but with an English country-house interior. The princess was in demand from Vogue for jewellery stories, not least because her husband commissioned exaggerated pieces from Cartier and Van Cleef & Arpels. Beaton photographed her in a diamond bracelet by Cartier, emblazoned with an emerald, which he recalled in wonderment was “the size of a small fruit”.

Beaton was 26 when he photographed the new Duchess of Westminster in 1930 – the year that saw both the publication of his first book, The Book of Beauty, in which he elevated to the pantheon those he considered worthy, and an exhibition in Mayfair that drew in London society. The duchess was noted in the book and made the cut in the show on account of her “raven’s wing shingle and magnolia complexion”, but her friend Edwina Mountbatten, equally prominent, almost as wealthy, made neither. Mountbatten would inherit Brook House, one of the most lavish houses in London. Eight hundred tonnes of marble were used to create and panel the great hallway, allowing it to be known, unkindly, as the Giant’s Lavatory. On Mountbatten, Beaton was at his most gnomic: “She is almost the perfect pattern for the novice,” he told Vogue. “Copy her weighty elbows…”

Many others from The Book of Beauty find a place in the show, including Margot, Countess of Oxford and Asquith, an early patron. Evelyn Waugh enjoyed lampooning Beaton’s portrait of Margot in Decline and Fall (1928), but he had even more fun lampooning Beaton himself, as the society photographer David Lennox, who emits “little shrieks” and makes “straight for the nearest looking glass”. Beaton and Waugh had never got on since prep school.

Another Beaton favourite was Paula Gellibrand, the Marquesa de Casa Maury: “the first living Modigliani I ever saw”. Above all, she personified his ideal of feminine beauty: “very long, thin, almost scrawny neck” with “no chin at all, an abbreviated nose… a general bird-like appearance and heaps of paint, especially around the eyes”. He called her, admiringly, “photograph proof”, believing that if she were taken upside down “with the blood rushing in every vein of her head, the result would be just as attractive”. Looking at the marquesa, poised and still, her eyelids heavy with Vaseline to accentuate their natural droop, it seems unlikely she’d ever have allowed herself to be turned upside down.

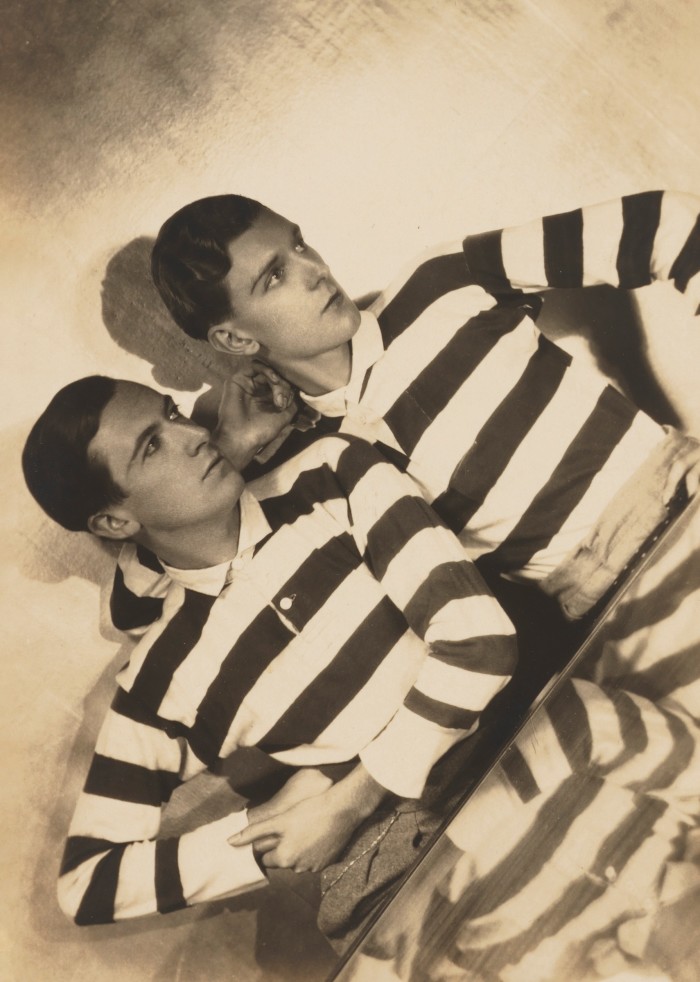

The Book of Beauty is a social record nonpareil, the shimmering portraits enlivened by Beaton’s writing, a stream of consciousness of rapt adjectives and flattering metaphors. “Exciting new friends appeared like mushrooms – some brilliant in promise, others already eminent,” he recalled. “They became willing sitters for extremely unconventional photographs.” His prints were passed around like contraband and marvelled at. Reality could be touched up or toned down according to whatever representation of reality the sitter required (or the photographer considered “right”). “I couldn’t believe that ever, ever for one moment I’ve looked as beautiful as this,” exclaimed Stephen Tennant.

Not everyone was pleased to be among the Bright Young Things. The Jungman twins were posed as if conjoined at the head. Lady Loughborough was nearly asphyxiated while holding her breath under a decorative Victorian bell jar. Lady Cunard took such offence at being described as a society hostess that she threw her copy of The Book of Beauty into the fireplace. Meanwhile, Virginia Woolf, who had demurred at sitting for Beaton, was indignant to find herself there after all, rendered as a pen-and-ink sketch. She took her outrage to the newspapers, which delighted Beaton. (“Anything for the uprise!” he’d once announced.) Any publicity was good publicity.

Alongside Beaton’s books, Loelia’s memoir Grace and Favour (1961) and Cocktails & Laughter (1983), a compendium drawn from her photo albums, also serve as a record of interwar life lived at the highest level. She was born in St James’s Palace and likely the last debutante to “do” the Season in a horse-drawn brougham. The Tatler labelled her “squadron leader of Society’s Young Brigade” and she marshalled them from party to pageant to charity ball and back again. In this milieu she is remembered – despite some misgivings on her part – for popularising two activities emblematic of the Bright Young Things: the treasure hunt around London and the bottle party. The former, devised in 1924 with the Jungman sisters and Enid Raphael, alleviated boring afternoons; the latter, vacant evenings.

At their height, Loelia’s treasure hunts threatened to become a mania and their participants a mob of descending Furies. Clues became more arcane, conveyed, perhaps, by flags hanging from a tall building, baked in loaves of bread from the Hovis factory on the Embankment, hidden in the imaginary news of a specially printed front page of the Evening Standard. Inevitably, the real papers could not resist such attention seeking, and Loelia believed that the term “Bright Young People” originated around this specific entertainment. Certainly the term (and its variant, “Things”) had gained greater currency by 1925, around the time interest in the treasure hunts began to wane.

For all their shameless displays of wealth, the Bright Young Things inhabited a curiously democratic time and place. In this rarefied realm, talent could defray any inadequacy of social rank. The composer William Walton was born in Oldham, the son of a jobbing musician. A child prodigy who could sing snatches of The Messiah before he could speak (according to his mother), he was taken up by Osbert Sitwell and his younger brother Sacheverell while still a teenage undergraduate and for the next 15 years they looked after him, all expenses paid, in their Chelsea home (it might have been a very different story, Walton surmised, if he had been a young and struggling writer).

Beaton himself was the son of a timber merchant. Though he was born to relative comfort, his family’s fortunes waned as he grew up, and Beaton, perennially dissatisfied with his routine upbringing, longed to escape. “My ambition to break out of the anonymity of a nice, ordinary, middle-class family certainly manifested itself in other tiresome outward forms; one of which was the pleasure I took in surprising, or even shocking, people by the inimitable way in which I adorned myself.”

The world of The Book of Beauty was one to which Beaton was instinctively drawn and to which he felt he ought to belong, but his was – initially – an outsider’s eye, scrutinising, recording, marvelling. If he had been born to it, he might have been less insightful of it. By practising the art of artifice, he elevated his friends to the level of minor deities, exotic as rare orchids, shimmering, iridescent, otherworldly, but in so doing he was also transforming himself, making “Cecil Beaton” an immortal. “I suppose,” said his friend Stephen Tennant, “your camera is enchanted…”

Cecil Beaton’s Bright Young Things will be at the National Portrait Gallery from 12 March to 7 June; npg.org.uk

Comments