Being money savvy is necessary, but not cool, say millennials

Do you have to be “boring” to be good at managing money? It might come as a disappointment to FT Money readers, but this is a commonly held perception among young people, according to the Money Advice Service.

The government-funded service which provides free and impartial advice has been asking 16 to 25-year-olds about the strategies they use to manage their cash, and the areas that they need help with.

Its latest research presents some challenging questions for young people, their teachers, parents and the wider financial services industry.

Despite its “boring” image, the good news is that learning to manage money well is important to the 500 young people who took part in the project. More than half of them ranked this above having a job they enjoyed, and even buying a home. The bad news? Having a social life was seen as a higher priority.

“Money management is recognised by young people as a rite of passage as they come of age and enter adulthood, but the problem is most of them feel ill-equipped to do it,” says Deborah Mattinson, founding partner of BritainThinks, the research and strategy group that partnered MAS on the project.

Overall, one in five young adults said they were not confident about managing their money, rising to one-quarter of 16 to 18-year-olds. Nearly two-fifths said they did not know where to go to get help with their finances.

Yet the need for young people to get to grips with money matters has arguably never been greater. The average graduate will leave university with debts of more than £40,000 — a huge worry for many who took part in the project.

“Times have changed,” says Ms Mattinson. “Overall, young people are pessimistic and fearful about the future as the financial outlook feels very much worse for their generation than ones that have gone before.”

Here we take a look at the key findings from the study, providing some practical tips and suggestions for young people seeking to gain more control over their finances.

When it comes to managing their money, many young people feel conflicted. On the one hand, it is seen as a burden; on the other, a mark of responsibility and independence.

“There is a tendency among young adults to think that if they were to manage their money well, they would have to become more organised and less spontaneous,” says Charlotte Malton, senior research executive at BritainThinks.

To supplement the survey data, 30 young people aged between 16 and 25 took part in financial workshops held in London and Manchester.

“Very few would admit to keeping a strict budget or using money management strategies as they felt friends would see them as boring for doing so,” she adds.

“You don’t want to be that friend who always says, ‘I can’t afford to do that’,” was the view of one female graduate from Manchester.

So what sort of a person might be good at managing money, in the view of those surveyed?

“At the weekend, they are probably more likely to stay in and watch TV, or cook something like spaghetti. It’s probably not the most exciting person,” says a female school leaver from London.

“Managing money well and promoting short-term happiness are often seen as in direct conflict and where this conflict occurs short-term happiness usually wins,” says Ms Malton. While young people were prepared to make trade-offs between money and happiness, they rarely thought about how managing their money well now could facilitate happiness in the future.

In the survey, three out of five young people agreed that their lives would improve if they could manage their money better. The hard part? How to achieve this.

In the workshops, a worrying sense of bleakness emerged. Many young people questioned the point of saving for a housing deposit, faced with the scale of the sums involved.

“Many felt they were never going to get there anyway, so they might as well spend the money on a festival ticket,” says Ms Mattinson.

Understanding the benefits of good financial habits in the medium and longer term proved a harder concept to grasp.

Nearly three-quarters of those surveyed agreed that self-control was more important than actual knowledge when it came to managing their money.

Efforts made in exercising willpower were considerable. To meet short-term savings goals, many workshop participants said they resisted the temptation to spend by giving money to a trusted family member immediately after payday. Paying money into a separate savings account — particularly one with a notice period to withdraw money — was a more conventional approach.

“If they did have access to their money, they didn’t trust themselves not to spend it,” Ms Malton adds.

As well as lacking confidence in their own money know-how, more than one-third of young adults surveyed said that if they needed help managing their money they would not know where to get it. Two in five said they did not usually seek guidance when making financial decisions.

Tellingly, both university and school leavers wished they had been taught more about how to manage money at a younger age. In total, 85 per cent of those surveyed said they were not taught enough at school.

In the workshops, university leavers said they wished there had been more help and resources provided to them while they were studying — particularly when it came to understanding loans and credit products.

While most young adults surveyed said they had spoken to friends or family about money in the past year, in the workshops there was strong opinion that money was a “taboo subject”. Few were comfortable discussing their finances, and felt that, if asked, they needed to give the perception that everything was OK — something for parents to bear in mind.

While many young adults kept an eye on their money at least occasionally, few did so regularly or managed their money with a structured approach.

The majority of those surveyed had checked their current account balance in the past year, but 20 per cent did not report checking their bank statements. While 44 per cent of young adults reported having made a budget to manage their spending in the past year, women were more likely to do so than men (49 per cent versus 39 per cent).

In the workshops, a budgeting strategy used by several young workers was described as “pay yourself first”. As soon as payday arrived, they covered their bills and essentials first before spending money on products or experiences they knew they would enjoy.

One female graduate from London confessed that she thought budgeting meant the same thing as short-term savings “because we only budget in the short term”.

Some workshop participants had a more structured approach, using spreadsheets to track their spending or setting up a direct debit to their savings account to put aside a certain sum in a separate pot. However, they tended to be older, with stable jobs that paid a regular salary.

Ms Malton notes that few participants thought about managing money beyond 12 months. “Partly, this was linked to the amount of change that is going on in their lives,” she says. “Many mentioned uncertainty about where they would be living or working in a year’s time and without clear goals for this, they found it difficult to plan on a longer-term basis.”

Pensions and investments were seen as something to do “in the future” and workshop participants confessed to being clueless about how to take out these products. The “baseline” of having enough money to pay for rent, bills and basic necessities was seen as a prerequisite to engaging in more sophisticated money management strategies.

Only 20 per cent of those surveyed reported saving into a company or private pension plan in the past 12 months. The likelihood of having done so was highly dependent on age: the figure doubled to 40 per cent among 22 to 25-year-olds who were more likely to be in stable, full-time jobs.

This number could have been boosted by auto-enrolment, which has swept millions of people into saving small amounts for their pensions. Before Christmas, the government announced the policy would be extended to 18 to 21-year-olds — albeit at some point in the next seven years.

Despite the plethora of budgeting apps aimed at young people, most of the workshop participants kept track of personal spending in their heads, relying entirely on intuition.

More often than not, the way budgeting was conceptualised was by weighing a specific measure of spending against a specific spending goal — for example, needing to sacrifice three nights out to buy a £100 watch.

“This was a consistent feature of young adults’ conversations throughout the workshops,” says Ms Malton, adding that marketing bosses in the financial services industry should take note. “Adopting this approach when speaking to young adults about money management could help communications cut through and feel meaningful.”

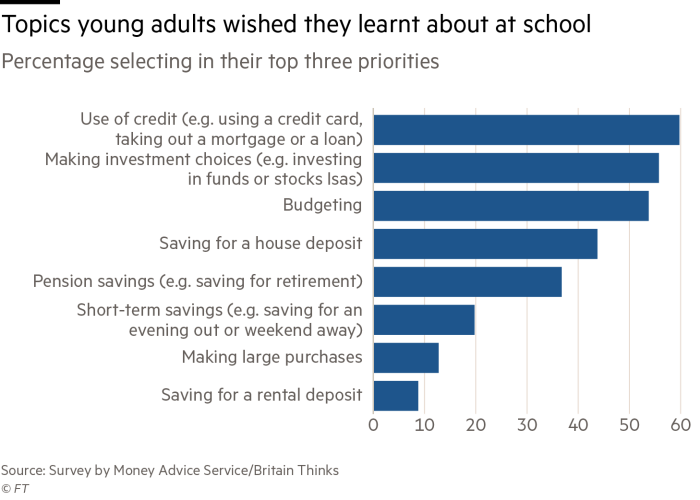

Young people are extremely wary of taking out credit, yet it also comes top of the list of financial topics they want to learn more about.

In terms of their financial priorities over the next five years, finding out more about the use of credit also came top, ranked above making investment choices and pension savings by survey respondents.

Despite their interest, few young people in the workshops had a credit card. Most had heard horror stories of indebtedness, or had been warned off by family or friends. One participant even suggested that credit cards should come with a “health warning” akin to cigarette packets. But equally, participants knew that a credit rating was necessary to rent a flat or get a mortgage, so were actively looking to use credit responsibly to achieve this in future.

One male university leaver relayed the experience of missing a direct debit on his phone contract. He didn’t think this was a big deal, but it quickly turned into a “negative cycle” where bank charges for missing the payment breached his overdraft limit, triggering yet more charges.

“Then I got a really bad credit rating,” he says. “I’ve gone past it now, but at the time I thought, why didn’t I know about any of this stuff?”

The research was aimed at those moving from education to the world of work, as part of the Money Advice Service’s wider mission to improve financial capability among young people.

“These are prime, teachable moments where we can engage with young people at a crucial juncture to make a financial plan,” says Michael Royce, proposition manager at MAS.

“We’re not trying to present good money management as exciting and sexy — it isn’t. But without it, you can’t do all the exciting things in your life that you want to.”

Methodology

BritainThinks conducted a quantitative survey of 470 young adults, weighted by age, gender and region to be representative of all British 16 to 25-year-olds. Additionally, two financial workshops with a total of 30 young people were held in London and Manchester.

Comments