PhotoEspaña: the gaze turns inwards

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

PHotoEspaña, like Spain in general, has faced difficult economic circumstances this year, and it has drawn in its horns a little. The photography festival’s theme is tighter and more manageable than some in the past: it focuses closely on Spanish photography. That was an introspective decision, curiously in tune with a new introspection in photography in general. With the root-and-branch disturbance brought by the irruption of computers, a substantial chunk of photographic activity is now about what it means to take and use photographs.

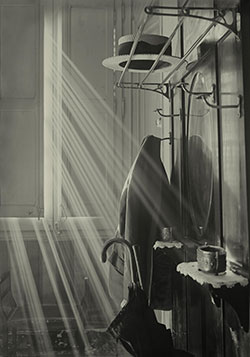

Spain underwent a long period in the mid-20th century of censorship, exile and loss, and one of the great strengths of this year’s festival is a broad sense of recovery of unknown historical material. A fine exhibition is devoted to Antoni Arissa, a photographer and printer almost wholly forgotten until now, whose trajectory in the 1920s-30s took him from allegorical pictorialism to a version of modernism.

Arissa is not in the highest rank of photographers for originality, but he is all the same entirely deserving of renewed attention. The curators have chosen carefully to make modern prints where they had no earlier ones, and by scrupulous scholarship have brought a photographer back from oblivion. That show sets a high standard in collaboration. Telefónica, through its foundation, is now well into a long programme of actively restoring to visibility lost or near-lost Spanish photographers; its work here with the Catalan Museum of Art and the University of Navarra (which will soon be opening an ambitious new museum of its own remarkable collections) represents an exemplary combination of scholarship, sponsorship and curatorship.

There is nothing at all wrong with that kind of careful introspection. Elsewhere, it blows up. P2P is a disastrous exploration of contemporary practice in which the processes of new photography are deemed more interesting than the results. A markedly vague collaboration between the curators and 24 artists has resulted in a pile-up of a show in which ugly or poorly made artefacts on the wall are justified only as illustrations of theoretical positions that nobody outside the little world of contemporary art practice need care about.

The base premise might have been interesting: that the new photographer swims in a digital stream and does other things than make, select and distribute his best pictures (archiving and re-purposing pictures that already exist are now common photographic gestures). And to put some things online to make those points might have made sense.

But to claim a major art-space in central Madrid and then spatter its white walls with works which amount, in effect, to a declaration of contempt for the entire traditional concept of the art-exhibition smacks of wanting to have one’s cake and eat it.

The show opens with a single Latin word (punctum) which those in the know will recognise as an allusion to Roland Barthes. It moves on to two bad seascapes displayed upside-down; a shapeless pile of foam-rubber (included on the grounds that it can be stained by exposure to light and therefore has some connection to photography); a video of walking figures, also projected upside-down; a collection of boring colour studies of bubble-gum on terrazzo walls or floors; and a pathetic group of little prints containing a single word each. These are arrived at by an arbitrary process whereby the video of every Christmas speech given by King Juan Carlos is analysed for its “average colour” (a hideous goose-shit brown) and the word which occurs most frequently if you discount “Spain”. Unsurprisingly, the word “society” recurs a number of times.

In this exhibition self-indulgence vies with pretension to produce a show of insultingly poor results. I object to the absence of care for the materials, the contempt for the viewer, the indifference to communication and the triteness of the ideas in play. I cite no names, not to spare the blushes of those who made it, but to deprive them of one chance to find themselves tagged online.

Fortunately, a number of the same ideas are aired in a grown-up manner elsewhere. The veteran photographic punster Joan Fontcuberta has curated a much more searching study in the same territory. With Photography 2.0 he attempts to make sense of the new possibilities and roles. Is a photographer now more of an editor than he was? Is the notion of identity changed by the new free availability of self-portraiture to everyone? Privacy, voyeurism, representation, the distribution of pictures and the new ways we can recover them from the new repositories are all in question as rarely before. These are big issues, and in a varied and visually exciting show, Fontcuberta comes a long way to making them accessible.

We would not necessarily expect firm answers, and indeed, a number of the works chosen by Fontcuberta raise questions of their own. A series by Txema Salvans, for example, shows prostitutes on the Mediterranean coasts of Spain, working by the sides of roads. Using metadata held within the image files, we are able to map their locations accurately, even view them ourselves on Google or similar mapping programmes. In theory, this allows us a new-sociological glimpse of hardship.

But one of the difficulties of digital photography is that it is very hard to identify pictures by style alone, and therefore one man’s prostitutes by the side of a road look very much like another’s. For all the customisability of digital imagery, neither a pixelated screen nor a printed digital file have anything like the varieties of surface tone and texture that were readily available in a darkroom. Various other enquirers are, in fact, pursuing closely similar courses of work, among them the British-based artist Mishka Henner.

Even leaving that aside, staring at prostitutes without them knowing that you are doing so is prurient and voyeuristic even if done in the pursuit of supposedly higher motives such as showing how documentary photography is changing or how patterns of migration force people into demeaning and dangerous work. It is one of the virtues in a complex show that the curator wants us to meet these questions head-on. The new photography is not straightforward in what it is, and the codes of behaviour (for practitioners, legal authorities, users, publishers, archivists, viewers, etc) are far from clear yet. That’s exhilarating and will continue to be.

Madrid is awash with photographic exhibitions. A wonderful examination of the Spanish photobook from the 1930s to the 1970s at the Reina Sofia museum would be worth an article in its own right. Again, it’s a solid work of recovery of little-known work barely considered until recently. So is a really savage group of 1950s and 1960s satirical collages on The American Way of Life, by Josep Renau, an artist who would certainly be better known worldwide had the history of Spain been different.

A number of other one-man shows are excellent: one on José Ortiz Echagüe (1886-1980), a brilliant specialist in the gloriously rich Fresson carbon printing process who makes a nonsense of so many of the artificial divisions we like to impose on artists. Ortiz Echagüe was a modernist with a romantic sensibility, a scientist and engineer who achieved his effects by emotion. His main subject matter was the types of people who made up Spain, photographed both as individuals and as symbols of their kind. The survival of his archive and the work done on it at the University of Navarra add up to an exemplary demonstration of the importance of keeping unfashionable work until its time comes round again. Another solo exhibition, showing lovely wit and a sharp social eye, focuses on the colour magazine portraitist Chema Conesa.

The English photographer Vanessa Winship is given a major and interesting show at the Mapfre Foundation, her first retrospective. Not being Spanish, her show is not officially included within PHotoEspaña. It just goes to show: even in a straitened year with one huge failure, PHotoEspaña gives every photography festival in the world a standard to aim for.

PHotoEspaña, Madrid (with outposts elsewhere) until July 27, phe.es

Comments