The collections of Stanley J Seeger

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Stanley J Seeger was an art collector whose love of art was exceeded only by his love of collecting. Heir to an oil and timber fortune, he voraciously assembled art works and miscellaneous objects that fascinated him; and then happily dispensed with them as soon as he regarded his mini-collections as complete, or just got plain bored. And then he would start all over again.

He famously sold his entire holding of 88 works by Pablo Picasso, brought together painstakingly over a lifetime, in one spectacular sale at Sotheby’s New York in 1993. It was a rotten time for the art market yet the sale still fetched over $32m. If the same pieces were to be sold today, they would raise up to four times the amount.

In 2001, a substantial tranche of the rest of his collection was sold on another famous evening. “The Eye of a Collector” sale, also at Sotheby’s, raised $54m, including a then record-breaking $8.6m for a Francis Bacon triptych, “Study of the Human Body”. Other highlights included masterpieces by Joan Miró, Jasper Johns, Max Beckmann, and still more Picassos, acquired since the 1993 sale. It was a clear-out of extravagant proportions.

Seeger, who died aged 81 in 2011, was a rare kind of collector. Most art lovers who acquire works at those exalted levels do so, at least partly, out of some glorification of the ego, or display of power, or from sheer machismo (they are nearly all men). But Seeger was different. His was not a collection, said the writer Michael Raeburn in an essay for the 2001 sale catalogue, formed for ostentatious display; or one designed to “salt” works by his protégé artists; or one that was assembled with the help of advisers and dealers.

It was, said Raeburn, “the collection of a magician.”

…

The magician did most of his collecting with the help of his partner of 32 years, Christopher Cone. The two men met in 1979, when Seeger was 49 and Cone 25. Seeger whisked Cone to Greece on a private jet, and then when they returned to England they bought a Tudor mansion, Sutton Place, for £8m, the highest sum then paid for a British property.

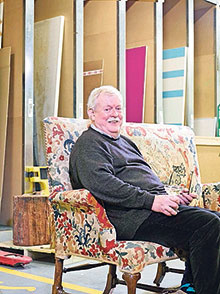

Cone is in London to help supervise what promises to be the final sale from the collection, which he helped Seeger piece together. On March 5 and 6, Sotheby’s will put up for auction what is not the most valuable but, in many ways, the most interesting and certainly the most private part of the hoard. Here are the objects that Seeger and Cone lived with in their inner sanctums. The range is diverse and eclectically drawn, which is reflected in the sale’s title, “One Thousand Ways of Seeing”.

“Stanley would have felt completely comfortable here,” says Cone as we walk around a viewing room at the auction house’s warehouse, which is full of mind-bending curiosities. “It is like seeing old friends again.” Some of them are of astounding cultural importance: rested on a lectern is a shooting script for Citizen Kane (1941), which turns out to be the personal copy of the film’s director Orson Welles. “Stanley thought it was the greatest film ever made,” explains Cone. “He saw it and had to have it.”

A sideboard is sandwiched between Winston Churchill’s armchair (“I’m not sure I’ve ever actually sat in it,” says Cone) and Rudolf Nureyev’s coat-rack (“We bought it together with his copper bath, which was completely useless”). On the sideboard itself, more fragments from history: a Fabergé-framed photograph of Tsar Nicholas II in a British military uniform, poignantly dated 1916; an exquisite Ming dynasty silver octagonal plate; a superb Tiffany lamp.

“What Stanley was doing in his collecting life was creating episodes, like little nests,” says Cone. “It was his way of keeping the outside world at bay. He was a very private, and very shy man.” He picks up a small teapot and hands it to me. “It belonged to Lord Nelson,” he says. I ask if they had ever used it. “Oh yes. Everything we bought, we bought to use.”

Every piece in the room prompts an anecdote from Cone. A silver jug in the shape of a communion flagon, of all things, was owned by Al Capone. “To a ‘regular guy’ from the boys” is the slightly chilling inscription: a 1932 Christmas present from Capone’s underlings. Cone remembers how he and Seeger used to offer their guests Bloody Marys from the vessel. “They would have the most extraordinary reaction when they found out where it came from. They wouldn’t touch their drinks after we told them!” Hard to resist a frisson of fear when confronted by those ironic quote marks around “regular guy”.

In the opposite corner of the room is an ancient Mexican terracotta sitting figure, head resting on a hand, with an expression of resigned anxiety. It reminds Cone – of course it does – of the evening Ava Gardner came to dinner at their London flat. “She asked Stanley to show her the bathroom. He took her upstairs, and she tried to seduce him. She flung herself on the polar bear rug in the bedroom, looked around, and said, ‘Honey, those pre-Columbian figures!’”

The lines are delivered with the ease and timing of a stand-up comic. What comes across is the fun that the two men had in their collecting. When they bought Sutton Place, one of the first things they did was to put the Bacon triptych in the Great Hall of the mansion. “It caused a scandal,” recalls Cone. “You didn’t do things like that in a Grade I Tudor mansion. Mind you, they never got to see the Picasso upstairs. Except when we held concerts up there, and there would be a moment, you could just tell, when they set eyes on it – it was a highly charged, erotic painting – and there would be this sharp intake of breath. It was such fun!”

I ask if the two men ever disagreed over any part of the collection. “Oh, I got very frumpy sometimes. Stanley bought an oversized Victorian chair once, which was hideous. But I didn’t really say very much. I always gave in. And Stanley was always right.” He says he would have liked to have bought a Mondrian or a Kandinsky. “But Stanley was not into pure abstraction. Although he did buy me a Kandinsky print once.”

…

We sit down to lunch in the middle of the viewing room, and enjoy a cold salad spread. The table is laid with more items from the collection that are all up for sale: De Lamerie dinner plates engraved with the cypher of George II; a pair of 17th-century candlesticks: tortoise-shaped service bells with bell-push tails; 19th-century Baccarat crystal glasses. Cone treats them all as more old friends. “Two and a half years ago, I was living with all these things,” he says, with the slightest note of melancholy.

Seeger was born in Milwaukee in 1930, into a rich family – the wealth came from his Scottish maternal grandfather – that revered antiques and first editions. He went to Princeton to study architecture but switched to music. He travelled to Florence (“a sensible place”, he once described it) to study under composer Luigi Dalla-piccola, and more frequent trips to Europe followed, during which he fell under the spell of contemporary art.

In the 1960s, he settled in Greece, and became a citizen of the country. “It was a place you could disappear to, a simple world, full of musicians and writers,” recalls Cone. Seeger moved to the Canary Islands following the military coup in Athens in 1967, and finally settled in London. (His love of Greece led, many years later, to the foundation of a Center for Hellenic Studies at Princeton.)

“He was a very depressed and sad person when I met him, smoking and drinking too much – and I wasn’t that radiant either,” Cone says of their first encounter. “We were two unhappy people who wanted to cheer each other up, and that is what we did for the next 32 years.”

The 1980 move to Sutton Place, the former property of industrialist J Paul Getty, was, says Cone, a way of exercising Seeger’s taste for decoration. But the two men had underestimated the reverberations of taking over one of Britain’s most historically resonant private properties. “We were lambasted in the press for doing the things that we did there,” says Cone. He adds that Francis Bacon “loved” the hang of his triptych in the hall. “He came to look at it but we weren’t there. If anyone famous came to look at Sutton Place, Stanley made sure we were out of the country.”

In fact, the two men rarely spent very much time at the mansion and moved out just six years later. When I ask him why, Cone says: “I don’t think Stanley ever anticipated that it would shine such a strong spotlight on himself. It didn’t suit him, and it didn’t suit me. The meter was running from the day that we moved in. We felt very lonely there, very exposed: two men living together in this great big country house. It was a statement too far.”

What surprised many about the Seeger collection was the apparent freedom and regularity with which it was dismantled. How did it feel, I ask Cone, to get rid of 88 Picassos in one go? “It felt hairy-scary. But it had a good outcome. Stanley didn’t want the pictures any more. I remember he said to me one morning, ‘Chris, will you keep your eyes open for a Rose period? That’s all I need now.’ We found one, and the collection was done. The crossword was complete.” It was time for the paintings to find new homes.

We talk about the prices fetched by Picasso art works now – and the Bacon triptych sold last year by Christie’s for $142m, a record for an art work sold at auction. Did he regret not hanging on to the art a little longer? “No, not at all. And neither did Stanley. We never looked back.”

…

Melanie Clore, chairman of Sotheby’s Europe, who dealt with the various sales from the Seeger collection over the years, says the two men “define what collecting is all about. They bought amazing pictures, and they bought things that they loved themselves. And that is a characteristic that defines serious collectors.

“What I thought was so clever was that because they were so private, they were also so free. Very few people knew them in the art world. They weren’t hounded everywhere they went. They bought things that gave them enormous pleasure, and really engaged with them. Their passion was addictive and compelling. And theirs was a real love affair.”

It all happened so recently yet seems to belong to a different age. The art market today is fuelled by testosterone, and thrusts itself into the public eye with merciless self-aggrandisement. Seeger and Cone played to more gentle rules. Cone says he remembers going with Seeger to a viewing of the Picasso sale, and overhearing two people saying with some certainty that Seeger didn’t actually exist, and it was all a front for the auction house. “I thought Stanley would explode! He loved that!”

Seeger was no tastemaker: he was a taste-defier, who combined the finest of eyes with a relentless curiosity for the small objects that had been brushed by history. He also had the aesthetic confidence, and the audacity, to challenge the conventions that sought to keep works of art in their own, discrete places. He was a man who, as the architect and designer Sir Hugh Casson said, regarded “the chic as a badge of insecurity and the conventional as a signal of surrender”. And when he made a statement too far, he withdrew from the attending spotlight, “like a mouse scuttling back into his hole”, says Cone.

Cone happily admits to “hanging on to Seeger’s coat-tails” during their exhilarating years together. “But we were a team. I think, in the nicest possible way, that he needed my help. I was his partner, lover, personal assistant, minder, attack-dog. I was Stanley’s passe-partout.”

He takes a last look around the viewing room but there is humour, rather than sadness, in his eyes. He waves an arm around him. “This is Stanley’s memorial service. This is the best way to remember him. It is much more meaningful, and much more fun. Like a grand firework party.

“This was the private world of Stanley. And it was so much more important than all those Picassos.”

Peter Aspden is the FT’s arts writer. Read his column on ‘Dreams of a pre-modern England’

Comments