Tide turns in favour of coastal defences with Manhattan projects

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

There is a story told in New York, that in 1823 or 1824 (the exact date being its least compelling detail) two local hoaxers spread the tale that the city had become so overcrowded that lower Manhattan was about to sink into the harbour.

Their solution was that the island be “sawed in half”, with its bottom end turned around by horses and rowboats and reattached to balance everything out again. The project held out the tantalising prospect of employment for labourers struggling to find work after a yellow fever outbreak, according to novelist Joel Rose’s account.

Manhattan never sank, nor was it cut in two, but the threat posed by its waters is exercising New Yorkers again, in the midst of a new health and economic crisis. Some of today’s solutions sound almost as outlandish as the urban legend and their chances of success depend heavily on the political and economic fallout from the Covid-19 pandemic.

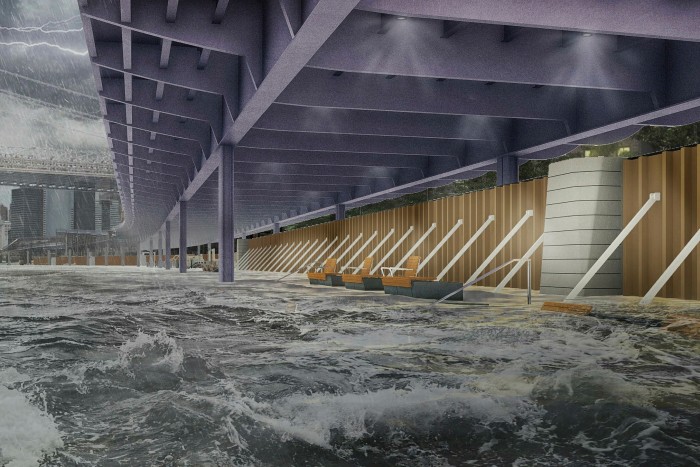

In the next few years, if all goes according to plan, walkways that flip up into barriers will be installed to protect the area north of the Brooklyn Bridge from storm surges, while at the eastern end of Wall Street, the shoreline will expand outwards, narrowing the East River. Glass-topped flood walls will ring the Battery Park City district to the west, while parks near the ferry to the Statue of Liberty will become hilly, landscaped berms, or raised shelves of ground.

Taken together, the four adjoining projects known as the Lower Manhattan Coastal Resiliency (LMCR) plan amount to one of the world’s most ambitious climate resilience initiatives.

Contractors should break ground next year on a plan that originated after Hurricane Sandy, the 2012 storm that killed 44 New Yorkers and cost the city $19bn.

Lower Manhattan generates 10 per cent of the city’s economic output, notes Jainey Bavishi, director of the Mayor’s Office of Resiliency. But it is a vulnerable hub: the city expects more than a third of its buildings to be at risk from storm surge by the 2050s, and a fifth of its streets to face daily inundation by 2100.

The LMCR plan was just a year old when the Covid-19 pandemic hit, upending city planners’ efforts to engage local communities, including thousands living in public housing. The classic planning work of soliciting residents’ views in small meetings is “challenging” during a pandemic, deadpans James Patchett, chief executive of the New York City Economic Development Corporation (EDC).

The immersive open house EDC consultation opened in February, using virtual reality to help residents visualise the threat posed by climate change to their neighbourhood, was shortlived. Mr Patchett says however that online engagement tools have since helped reach people who might never have shown up for traditional meetings.

The bigger challenge posed by the pandemic was financial. In March 2019, New York City allocated $500m to the plan, but that is a fraction of the expected budget. The project covering the financial district and the South Street Seaport alone is expected to cost $10bn.

New York faces its most serious economic crisis in decades, Mr Patchett notes, but the city’s part of the anti-flood funding is secured. Not so New York State’s Restore Mother Nature Bond Act, which was designed to raise $3bn for climate resilience projects: Governor Andrew Cuomo pulled it from November’s ballot in July, saying it was no longer “financially prudent”.

That leaves the LMCR plan, which was designed to attract public-private partnerships, in need of “catalysing” money from Washington, Ms Bavishi says. “Unfortunately cities often only access this kind of funding after a disaster. We really need to be able to access it in advance of a disaster,” she observes.

Mr Patchett hopes that Joe Biden’s election victory in November’s presidential election and the need to reanimate an economy stunned by coronavirus will create a once-in-a-generation opportunity for federal infrastructure spending.

“There’s going to be a clear need for projects that create jobs,” he says

and “this is something which is at the core of the Democratic agenda, at the intersection of climate risk and infrastructure spending.”

If federal funds do not come through, the city still has other options, Ms Baishi says, including offering some of the new land it is creating to developers.

New York’s coastal plan will be a test of most governments’ “inherent bias” to respond to immediate threats rather than prepare for more distant ones, Mr Patchett acknowledges, but the threat to the harbour is not a distant one. Already this August the city had to deploy “tiger dams” — large, water-filled tubes — to protect South Street Seaport as tropical storm Isaias approached. New York’s planners have learned from coastal resilience projects elsewhere, such as Rotterdam and Copenhagen. However, the challenges faced by the US’s financial capital are unique, Ms Baishi says.

“New York City is kind of a paradoxical place where it became a hub for economic activity and it became a cultural location because of its location on the coastline,” she reflects. “Now it’s the same location that threatens everything we’ve built here.”

Comments