Entrepreneurs use business school tool to buy companies globally

Simply sign up to the Business education myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Starting your own business is risky, so why not buy one that someone else has already steered through the perilous formative years? That is the logic behind the search fund, a specialist vehicle in which investors back a promising individual rather than an existing start-up team.

In the first stage, money is raised to pay the individual a nominal salary and expenses, sometimes for several years, while they hunt for an acquisition target in which they believe they can add value. Further funds are used to manage and grow the company.

The concept was developed at business school more than 30 years ago, led by Irving Grousbeck, a professor at Stanford Graduate School of Business in the US, who started teaching the concept to his MBA students.

Now, like that other Californian creation, the venture capital-backed model for high-growth tech start-ups, search funds are being tried in countries around the world.

In April, for example, Barcelona’s Iese Business School, one of the first business schools outside the US to teach the theory of search funds, is hosting a conference for entrepreneurs and investors involved in more than 20 search funds from five continents.

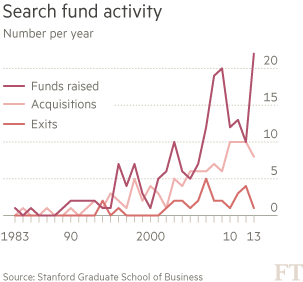

Since the first search fund was created in the early 1980s, almost 200 funds have been raised in the US and Canada. A study of 134 of these, by Stanford’s Centre for Entrepreneurial Studies in 2013, found that the aggregate pre-tax internal return on investment was a healthy 34.9 per cent.

This method of backing an entrepreneur, who can be given guidance to making a company acquisition, is seen as less risky by some angel investors.

Peter Kelly is a lecturer in management at Stanford who has also run search fund classes at Iese. “It is highly unlikely that an investor will lose all their money,” he says.

“People do it mostly because they want a return, but it is also fun and interesting to be involved with these potential chief executives and see them become real chief executives.”

Having said that, even enthusiasts like Mr Kelly admit that search funds should come with a warning sign. About a third of them lose capital after an acquisition, although he notes this is still better than the failure rate for start-ups, where investors lose all their money if the venture collapses.

“Running a search fund is hard to do,” he says. “If you start one and it goes wrong, it is a serious sidetrack to your career.”

This probably explains why in Mr Kelly’s classes of about 40 MBA students, only three or four each year choose to set up a search fund. “It is not right for everybody,” he says.

Europe should be ripe for search fund entrepreneurs because it has so many family businesses with succession problems. Recent years have also seen a more risk-taking culture among investors, encouraged by the emergence of start-up hotspots in cities such as London, Berlin, Stockholm and Barcelona.

However, understanding of the concept remains limited largely to those who have been through business school.

Furthermore, only a few schools have it on their curriculum, such as Insead in France and Singapore, and Harvard and Chicago Booth in the US.

Simon Webster was the first person outside North America to create a search fund, after reading about a US one on his MBA at London Business School in 1989. “Most [case studies] send me to sleep but this one kept me awake all night,” he admits.

Before his MBA, Mr Webster had only worked for large companies such as IBM. He dreamt of working for an entrepreneurial company but lacked “the big idea” as he calls it. Search funds were a way around this.

Although it only took Mr Webster seven months to persuade 70 US and UK-based investors to back him — raising £80,000 — he admits it was “bloody hard” to get the British backers on board compared with their counterparts.

Some of those British investors may have felt their caution was justified in the early stages since Mr Webster admits he almost ran out of money finding the right acquisition target. Fortunately, UK access to a greater amount of data on potential companies helped.

Under British corporate law, UK-registered businesses must provide the names and ages of all directors. This makes it easier to spot companies where the owners are approaching an age when they might be looking to hand over the reins.

In total, it took Mr Webster and his team more than three years to find their company, a prosthetic limb supplier called RSL. But after 10 years in charge they were able to create what Mr Webster calls “a nice return” for his investors, through a mixture of acquisition and organic growth. This increased turnover 10-fold to £30m.

Yet despite the success stories, expansion of the search fund market looks like a slow-burn activity. While there are now at least three private equity funds in the US dedicated to the model and some investors backing more than 100, it remains a niche concern even among business students.

Mr Webster now spends a chunk of his time sharing his story at LBS, Insead and Iese. This is not so much to help raise the profile of search funds, as it is to make people aware of the risks, he concedes, adding that search funds are never going to overtake the VC model of backing start-ups, even among MBA graduates, but that is not necessarily a bad thing.

Comments