Sex, violence and movie certification

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

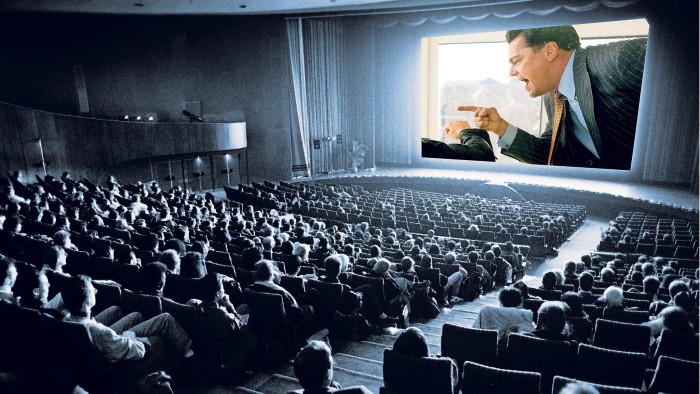

Martin Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street may be cleaning up at the box office but it has a very dirty mouth. It has officially been nominated for five Academy Awards and has already earned more than $220m worldwide. Unofficially, The Wolf of Wall Street is also the sweariest mainstream film in cinema history, with some viewers counting as many as 569 audible instances of the word “fuck” over its three-hour duration. Scorsese cut his original film to avoid the American NC-17 rating that has, since 1990, been regarded as the kiss of commercial death for a film but he has recently announced plans for a director’s cut, adding another hour to the film’s running time and, presumably, a proportionate increase in swearing, sex, drug-taking, and nudity.

Whether a film becomes more obscene the more swear words it contains is arguable: presumably the law of diminishing returns kicks in at some point. As the late film critic Roger Ebert once pointed out, when you’ve heard one f-word, you’ve heard them all. But film classification boards on both sides of the Atlantic disagree: the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) and the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) rule that teenagers’ films must have fewer than four “fucks”. More important than numbers is context: “fucks” can only be used as adjectives in such films, preferably in humorous contexts, and never as verbs. Who says grammar isn’t useful?

From its inception, cinema has provoked fears about debasement and corruption of its audiences, especially in terms of the way language is used. It is no coincidence that the term “dumbing down” was coined to describe the effects of Hollywood all the way back in 1927, one year before sound in film prompted the drafting of the notorious Hays Code, the self-censoring guidelines that defined Hollywood film from 1930 until 1968. Similarly, when it was established in 1912, the BBFC was originally named the British Board of Film Censors: the boundary between classification and censorship has always been porous.

Film classification boards were created to safeguard those audiences considered impressionable, and much of what film censors prohibited a century ago would also make modern audiences uneasy: incest and “sex perversion” remain controversial, although earlier audiences saw homosexuality as a perversion whereas we are concerned by depictions of paedophilia. There were similar concerns about the “hardening” (desensitisation) of audiences to violence, and these prohibited showing the methods of crime so that film couldn’t become an instruction manual for wrongdoing.

“Excessive” violence, nudity, sexuality have always been prohibited but our threshold for excess has been considerably raised. A recent study found that PG-13 films today feature three times more gun violence (2.6 times an hour) than films of the 1980s, while The Wolf of Wall Street includes male nudity in a sexual context, long the uncrossable frontier between pornography and mainstream cinema, as well as cocaine-taking and a lot of sex, including a gay orgy. Clearly, this represents something of a brave new world in mainstream cinema – and, some would argue, a depraved one.

But it may not be true that we are more accepting of profanity; rather, our definitions of profanity have changed. Broadly speaking, profanity has evolved from 19th-century prohibitions against blaspheming, through 20th-century preoccupations with sexuality and bodily functions, into 21st-century fears about hate speech and incitement to violence. As the BBFC’s regulation makes clear, we primarily use words such as “fuck” as an intensifier, and intensifiers only work if they are interpreted as intense. In the 19th century, “damn” and “blast” were unacceptable in polite conversation. Now, as one linguist noted, if a film character spoke in “damns” and “blasts” he would sound like Yosemite Sam. “Fuck” was always an indecent word but it was used in limited ways, to describe sexual acts. Now our notions of profanity tend to circulate around bodily functions and relationships. There is a reason why “motherfucker” is ruder than “fucker”: we are much more outraged by incest than by sex. By the same token The Wolf of Wall Street would have been far more controversial if its characters were espousing racist sentiments instead of saying “fuck” in every sentence.

…

The Hays Code specifically prohibited representing miscegenation (interracial sex), while the BBFC prohibited scenes “bringing into disrepute British prestige in the empire”, especially India, references to “race suicide”, “controversial politics”, or “relations of capital and labour”, all of which would render impracticable any accurate representation of slavery or colonialism. Today our attitudes have almost entirely reversed, as films such as Django Unchained (2012) and recent release 12 Years A Slave demonstrate. Their depictions of interracial violence are controversial but they would never have found mainstream distribution if either film had failed to condemn slavery from start to finish.

It is also true that the rules regarding cinematic propriety were resisted at the time in more ways than are often appreciated, as the battles over profanity in the 1939 blockbuster Gone with the Wind demonstrate. The story has long circulated that Clark Gable’s famous valedictory line, “Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn”, was targeted by the Hays Code, and that producer David O Selznick had to pay a fine. In fact, production records make clear that there was no particular fuss over Gable’s blaspheming. The profanity that did cause a struggle behind the scenes was the word “nigger”, which was in the script in the name of historical verisimilitude. The Hays Code had no problem with the n-word but the film’s African-American actors did, refusing to say it. Eventually, Selznick agreed to cut it from the script, in what might be seen as a bellwether for our changing ideas about what constitutes profanity.

We are not necessarily a more permissive society today: we control hate speech and harassment quite tightly. Until recently, society permitted fairly wide gaps between morality and legality – many things were legal that were considered immoral, especially in excess – but now we tend to legislate our morality, so that what is unacceptable is also criminalised. And profanity that is losing its ability to shock may retain an ability to entertain.

A hundred years ago, by contrast, film censors viewed comedy not as a mitigating context but an aggravating one. The BBFC and the Hays Code both banned obscenity and profanity “in word, gesture, reference, song, joke, or by suggestion (even when likely to be understood only by part of the audience)”. And they particularly objected to levity: the BBFC prohibited various forms of “irreverence”, while the Hays Code decreed, “seduction and rape . . . are never a fit subject for comedy” but they could be shown as long as they were duly deplored. The Hays Code, in particular, attempted to control the feelings of audiences, insisting that their sympathies must not be “thrown on the side of crime, wrongdoing, evil or sin”.

Rather sweetly, the authors of the code hoped that cinema might “affect lives for the better”, thus becoming “the most powerful force for the improvement of mankind”, for the promotion of “higher types of social life, and for much correct thinking”. This goal becomes less surprising when we realise how prevalent incorrect thinking was in early cinema. For example, a 1920 Harold Lloyd comic short called Get Out and Get Under is a series of gags about a young man whose car won’t start. He sees a passing junkie, sluggishly reeling and scratching his arms, who pulls out a syringe and shoots up; instantly he perks up, straightens his tie and begins to stride off. Lloyd steals the syringe from the junkie and injects it into his car, which gets coked up and speeds off without him. A 1929 film called Glorifying the American Girl glorifies her with full-colour full-frontal nudity, while many films between 1920 and 1934 featured homosexuality and lesbianism (not always negatively), prostitution, incest, sadomasochistic sex, various kinds of drug use (they were especially fond of cocaine), and even satanic cults.

Between 1929 and 1930, the Hays Office – which had been established in 1922 in response to a wave of outrage over film stars’ personal lives, not over films’ content – drafted an official code of practice, which began to be implemented immediately, but inconsistently: the so-called “pre-code Hollywood” films of 1929-1934 are actually a small, anomalous sample from a large group of increasingly conservative and moralising films.

By 1934, the Hays Code was in full force – but it is not true that it insisted that men and women be shown in separate beds (it stipulated only that bedroom scenes be treated “with delicacy and good taste”). Contrary to popular mythology, it was the BBFC that prohibited scenes of “men and women in bed together” but American films adhered to this proscription to secure distribution in Britain.

The Hays Code was generally more vague, and thus more flexible, in its prohibitions. Perhaps the best explanation of the way it was understood in practice was offered by F Scott Fitzgerald in The Last Tycoon, his unfinished 1940 novel, in which a producer explains the heroine’s motivation: “At all times, at all moments when she is on the screen in our sight, she wants to sleep with Ken Willard . . . Whatever she does, it is in place of sleeping with Ken Willard. If she walks down the street she is walking to sleep with Ken Willard, if she eats her food it is to give her enough strength to sleep with Ken Willard. But at no time do you give the impression that she would even consider sleeping with Ken Willard unless they were properly sanctified.”

Increasingly, however, writers, actors and audiences objected to this piety and hypocrisy; by the 1950s, American film had become absurd in its infantilising representation of adult behaviour. A backlash was inevitable, and as television made inroads into cinema audiences, film-makers began disregarding the censors, who were never legally empowered: the Hays Code was voluntary, implemented to avoid the commercial catastrophe of outraging audiences and provoking boycotts. By 1959, the now-classic comedy Some Like It Hot, flagrantly defying the Hays Code’s prohibitions against laughing at sin, didn’t bother to get classified at all but still became one of the biggest commercial successes of the year.

…

The 1960s were at hand, and things were about to change. Landmark literary trials permitted the publication of profanity and obscenity for the first time. In 1968, the Hays Code was formally disbanded and replaced by the MPAA, the modern classification system, which implemented similar categories to the BBFC, primarily targeted at defending children and accepting that adults no longer needed to be protected from realistically violent films. It didn’t take long for movies to become unrealistically violent, though the X-rating soon proved too blunt an instrument. In 1969, Midnight Cowboy was rated X for its depiction of male prostitution and drug addiction but went on to win three Oscars, including best picture (it remains the only X-rated film to have won an Academy Award).

In the 1970s and 1980s, X-ratings became associated with pornography, and ceased to demarcate mainstream films for adults that had sexual or violent content. Films such as A Clockwork Orange (1971), Last Tango in Paris (1973) and Blue Velvet (1986) were serious artistic ventures deemed beyond the pale of R (restricted) ratings but that, nonetheless, appealed to relatively large audiences, thus calling the whole ratings system into question. In 1990, the NC-17 rating was created, in response to films such as Peter Greenaway’s The Cook, The Thief, His Wife and Her Lover (1989), with its scenes of cannibalism and torture, which its director forcefully argued were permitted by artistic licence.

This remains the crux of the matter, the impossibility of legislating taste, and ever-shifting socio-historical contexts. It is not news that one viewer’s art is another’s pornography, and Anglo-American culture has not succeeded during centuries of debate, over painting, sculpture, literature, television, magazines or, indeed, film, in drawing a cordon sanitaire between the two. Nor are fears about seduction and imitation likely to disappear: they accompanied the arrival of the novel, as ministers sermonised against the corruption of readers by fictional “lies”, and have never left imaginative narratives behind, for the very good reason that we know that people learn from imitation, and from inspiration.

But imagination cannot be legislated, even if representation can be controlled. As long as we live in a culture that values free speech and artistic expression, we will continue to have debates about how to “classify” art, even if we don’t always think that’s the argument we’re having. The negotiations are ongoing – indeed, new regulations about swearing will be implemented later this month, after the BBFC consulted 10,000 members of the public about what they consider appropriate and inappropriate. They say there’s no disputing taste but that doesn’t stop us from trying.

Sarah Churchwell is professor of American Studies at the University of East Anglia and author of ‘Careless People: Murder, Mayhem and the Invention of The Great Gatsby’

——————————————-

Letter in response to this article:

Bad language mumbled offends no one / From Ms Sally Turff

Comments