Glamping at 12,000ft in Ladakh

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Dressed in rich red robes and sitting cross-legged on the floor, the elderly monk in front of us doesn’t look much like a tourism entrepreneur. Speaking softly, he bids us to enter. I catch my breath, wheezing slightly, having struggled up dozens of stairs in the thin Himalayan air to the very pinnacle of Thiksey monastery in the northern Indian province of Ladakh.

The Rinpoche, as the monk is known, has close-cropped white hair and a kindly smile. His quarters are sparse: plain wood panelling, a handful of golden Buddhist icons and the faint whiff of incense from the recently completed morning prayers downstairs.

The surroundings are, in short, suitably monastic. Yet look out of the window and down over the mountain-ringed Indus river valley below and you can make out a campsite; a luxury campsite, in fact, set on the monastery’s land.

Run by the Ultimate Travelling Camp, the project is an unusual commercial and spiritual partnership. “One of our monks was given responsibility to work with the camp,” the Rinpoche says, explaining that he will use any funds gained from supporting Ladakh’s first dalliance with “glamping” to educate the younger monks in his care. “So although we do not know anything about luxury, we do have a person assigned to help oversee its operation.”

My wife and I had arrived to test out the newly opened Chamba Camp Thiksey four days earlier. A brief early-morning flight from New Delhi took us to Leh, Ladakh’s capital, which stands more than 11,500ft above sea level. A half-hour drive out of town later and the monk mentioned by the Rinpoche greets us as we arrive at the camp’s front gate, offering blessings as we adjust to the scenery.

The view is extraordinary. Patches of green dot the valley, where clutches of spindly poplar trees rise up amid rustic farmland that is irrigated once a year by water melting off the glaciers high above. Yet the mountains that envelop it are dry and dramatic, with arid brown peaks rising up suddenly on each side. Perched on India’s most northerly tip, Ladakh sits between the flanks of neighbouring China and Pakistan. Until the 1970s, security concerns combined with the region’s inhospitable topography meant it was mostly closed to visitors. Latterly, the area has offered a rough-and-ready form of tourism, drawing intrepid visitors with its moonscape scenery, challenging hikes and craggy Buddhist temples.

Accommodation, however, has been limited mostly to home-stays and more basic hotels – something the self-styled “nomadic super-luxury camp” plans to change. “The concept was to go to places that didn’t have much in the way of infrastructure, where there weren’t any five stars. And there, Ladakh was an obvious choice,” says Prem Devassy, the facility’s general manager. After a trial period this month, the camp will be open fully from June next year for Ladakh’s four-month tourist season.

In the interim – as the much longer winter closes in and before the handful of mountain passes that connect the region to the rest of India are closed – the camp is to be packed up and sent off by truck, to be pitched in other corners of the country. Planned locations include a stop in Nagaland in India’s distant northeast, along with another at a jungle site in Dudhwa National Park, close to the Nepalese border.

…

We spend our first day acclimatising to the altitude and nosing around the site, which is dominated by two large marquees. One has comfortable sofas and a bar, where we are greeted with steaming mugs of Himalayan tea – a tasty concoction of Earl Grey, peach juice and sugar. The other provides a dining area, serviced by eight chefs and innumerable friendly waiters in uniform.

The plush bedroom tents, meanwhile, come with wooden floors and a four-poster bed, along with an elegant colonial-style chest and writing desk. Light-toned drapes cover the walls, while a huge air-conditioning unit blasts warm air to fend off the night-time chill. The en suite bathroom isn’t heated but is pleasantly furnished with warm fluffy towels and a brass sink imported from the UK.

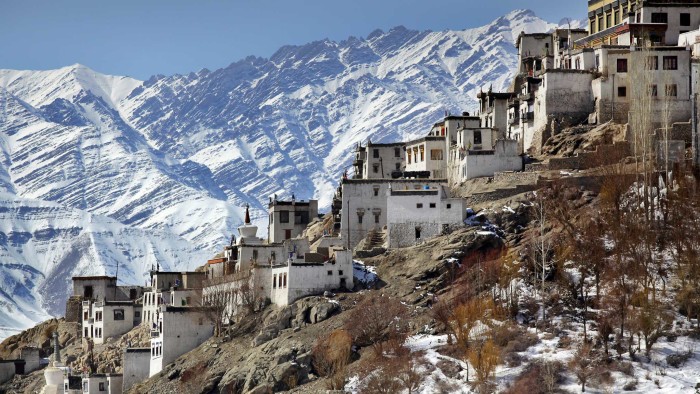

Much of the pleasure of the accommodation comes from just unzipping the front flaps and sitting on the balcony. To the left, over the river, lie the Himalayas. To the right, the Karakoram Range. And, straight ahead, the improbable jumble of Thiksey monastery itself, where a dozen storeys of white buildings are packed on top of one another, perched on a hill a few minutes down the road.

More of the area’s natural beauty rolls by as we drive down the valley to watch a polo match. Riders in cheery red and blue uniforms stand in line as we pull up and proceed to kick up clouds of dust as they gallop around on small ponies. The early evening sun casts moody shadows over the mountains, while local musicians helpfully strike up a tune whenever a point is scored.

The rest of our stay is mainly spent on gentle walks and mountain-bike rides in the nearby countryside. We pass an afternoon ambling around Leh, visiting its ancient palaces and windy backstreets. There are more adventurous options, too, including rafting trips down the Indus and much longer guided treks (which can add as much as a week to a trip). On our penultimate day, we plump for the latter, heading to the 17,300ft Wari La pass.

On the corkscrew journey up, herds of shaggy-haired yak and dzo – a half-yak, half-cow hybrid – stand near the roadside; we also spot a few furry treacle-coloured Himalayan marmots scampering about in the distance. But the real treat comes on the return leg, when we are greeted by a table and canopy on the mountainside, under which the camp’s staff provide a surprise three-course picnic. Polishing off my pudding, I realise it’s the highest meal I’ve ever eaten.

Yet amid all the dramatic scenery, I remain most intrigued by the relationship between the camp and its hosts. We visited the monastery at 6am one morning, clambering up the many steps to watch two monks standing on the roof, greeting the dawn by blasting on horns as the sun rose over the mountains.

Next came morning prayers, where dozens more monks gathered to chant in a darkened assembly room. The effect is surprisingly relaxed: butter tea is poured for guests, while the younger participants (some of whom look no more than four or five) grin playfully at each other in the pews. None of this, however, provides much insight into why the Rinpoche allowed the camp to set up in the first place, so I press for an audience, which is granted on our final morning, just as we head to the airport.

As our time in his chambers draws to an end, I ask whether he feels the monastery will benefit from its new visitors. “Ladakh is not what Ladakh used to be,” he says. “Today everyone is a little bit more busy. People used to come and volunteer and help us maintain our building but now we must look at other ways. The monastery cannot do everything.” Even so, he appears content with the venture, and enthusiastic about its future.

“The camp will help us in many different ways . . . and next year they have plans for 20 tents,” he says, looking down from his windows, seemingly happy to watch Ladakhi tourism prosper in his own backyard.

——————————————-

Details

James Crabtree was a guest of Ampersand Travel (www.ampersandtravel.com). It offers a package from £3,298 per person for seven nights, based on two sharing, including return flights from London, domestic flights between Delhi and Leh, airport transfers, five nights’ full board at the Chamba Camp, two nights’ bed and breakfast at Trident Gurgaon, and two half-day tours of Delhi

——————————————-

Boost from Bollywood: The kiss effect

Breathtaking, austere scenery remains Ladakh’s most obvious draw but its re-emergence as a popular destination for Indian visitors has also been helped along by a more glamorous source: Bollywood.

The region provided the backdrop for the final stages of Three Idiots, a 2009 production that went on to become one of the most commercially successful Hindi-language films of all time.

The film features the sparkling, azure-blue waters of Pangong lake, about 150km from the Thiksey camp. Reaching the lake from the camp involves a gruelling five-hour drive up and over an alarming mountain pass and then onwards into the Nubra valley, a strikingly isolated area that lies to the north of the capital Leh.

In the comedy’s final scene, actor Aamir Khan’s character is tracked down by his two best friends to the lakeside, ringed by dark, imposing mountains, where Khan has set up a school.

Accompanying them is Pia, the film’s female lead played by Kareena Kapoor, who embraces Khan by the water’s edge before the camera pans up and shows the final credits, streaming across a deep blue Ladakhi sky.

Despite its remote location, the site of Khan and Kapoor’s scenic final kiss has proved a considerable draw, kicking off a mini-tourist boom: the number of annual visitors to Ladakh has doubled to more than 170,000, just two years after the film’s release.

Comments