Business schools build on real estate boom

Simply sign up to the Property sector myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

When David Gleitman finished university in 2009, he, like many young finance graduates, wanted a flashy job in investment banking.

But the industry was collapsing just as he scoured his home town of Munich, in Germany, for work. Instead he ended up with an internship at an American real estate company. Four years later he was “hooked” and signed up for an MBA in New York to study the subject.

Mr Gleitman is not unusual: the financial crisis sent ripples of change through the global jobs market, where seven years after the crash the battered banking industry remains out of vogue among MBA graduates. In its place real estate, the scapegoat for the great recession, has soared in popularity among students as the market heats up and more jobs open in the sector.

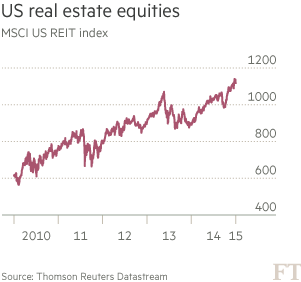

Investment yields and asset values for commercial property have surpassed 2007 levels, helped by years of ultra low interest rates and tight supply. Real estate investment trust, or Reit, prices climbed 80 per cent between 2010 and 2014, thanks to strong demand for offices and urban apartments, and higher returns when compared with bonds.

This boom has fuelled “huge” interest from students, says Nancy Wallace, professor of real estate at the University of California, Berkeley’s Haas School of Business. “They’re fleeing banking . . . real estate is cyclical, and MBAs follow cycles really closely,” she says.

Only 10.6 per cent of graduates from the world’s top 10 business schools are choosing a career in banking compared with 17.4 per cent in 2008. The 6.8 percentage point drop translates into a 40 per cent difference in banking’s popularity, according to a Financial Times analysis. At London Business School and Harvard Business School, its popularity has fallen 52 per cent.

Job insecurity, long hours and gloom surrounding the industry have steered the brightest students away from what was once an assembly line into banking and towards more entrepreneurial work. Technology companies such as Google and Facebook have usurped Goldman Sachs as a dream employer, but real estate has also emerged as an alternate path for a simple reason: there are jobs.

“First and foremost, people see that there are jobs in it now and . . . the ability to make a decent amount of money,” says Alex Lebowitz, an MBA student at New York University. “People are seeing that you can go into real estate and do really well, and work on interesting things that aren’t just working in a bank.”

Job prospects are often a determining factor for MBAs, many of whom shell out tens of thousands of dollars and forego full-time work to complete the degree. Observers note that in a world of record-low interest rates and a volatile stock market, property has become a more legitimate asset class to institutional investors. What was seen in 2006 as clunky and illiquid, riskier than stocks or bonds, is now a “primary asset class”, says Stephen Shapiro of Jones Lang LaSalle’s New York capital markets group.

This reputation is spurring a professionalisation of the industry and widening the scope of companies in the field. “A lot more pension funds and sovereign wealth funds dramatically expanded their portfolios into real estate,” says Stijn Van Nieuwerburgh, professor of finance at NYU Stern. This expansion is creating jobs in real estate beyond being a developer or landlord on the ground. “Employers are contacting me daily to circulate positions among our real estate students,” he says. Prof Wallace adds that Haas is placing all of its MBA real estate students into jobs.

Professors at Georgetown, NYU and Berkeley say they have seen a large rise in demand for real estate classes, with courses filling fast. Universities have opened or beefed up offerings to meet demand: Georgetown in April put $10m into a new real estate centre at its business school, following Rutgers and the University of Miami in 2013 and NYU in 2012. “Banking, at least at the time [in 2009], appeared to be shrinking and real estate finance was a natural place to expand,” says Prof Van Nieuwerburgh.

Apart from the ebb and flow of the cycle, real estate offers a connection to physical beauty and tangible assets, compared with illusory financial securities, students say. As banking loses the perceived safety it once held and the industry sees returns of less than a third of that before the crisis, students are re-evaluating what they want.

“[Banking] is what everyone thinks they’re supposed to do, as opposed to what they want to do,” says Matt Cypher, director of the centre for real estate at Georgetown’s McDonough School of Business. “I get plenty of calls saying: I’m just not happy here. I work seven days a week. I want something a little more tangible.”

Real estate jobs at private equity firms or hedge funds involve skills similar to banking: analysis, pricing and dealmaking. But it attracts a different type of student, Mr Lebowitz says. “If you look at NYC real estate it’s heavily male dominated . . . But it’s not quite as cut throat with the alpha males [as banking]. The culture is a little different.”

People skills are key, professors say. Prof Cypher adds: “They’re not sales people, but you have to have an innate ability to interact.” It also takes an appetite for risk as recruitment is less structured than that of banking or consulting, in which large companies come to elite campuses prepared to hire a set amount of students each year. Getting a job in real estate is less institutionalised, which makes breaking into the industry “definitely a challenge”, says Mr Gleitman.

While the property cycle has ushered in a newfound passion for real estate education, there are questions over how long the party will last. Already investors and analysts have flagged the possibility that property has peaked again, and prices will probably decline, if not fully crash, in the coming years, or even months.

As the US Federal Reserve raised interest rates in December, bond yields will rise, making property less attractive and hitting prices. Reit prices have already slipped 8.5 per cent since April. The Fed has flagged the sector as a hotspot in America’s economic recovery and a sign credit conditions are getting frothy.

With prices nearing all-time highs in some sectors, “we’ve very quickly moved from real estate is cheap, to real estate is expensive,” Michael Kirby of Green Street Advisors says. There is a 70 per cent chance that property prices will be lower a year from now, Green Street predicts.

This poses a risk that just as all these students march into real estate, they could be left out in the cold when they need a job and the market has retreated, echoing the history of their older banking peers. Ms Wallace says Berkeley is limiting class sizes to combat this risk, so students do not “all pile in while the cycle is hot”, and similar efforts are under way at Wharton and NYU.

For now students and universities will ride out the popularity of real estate while the market is hot, but many are mindful of the booms and busts that will determine their fate.

“Post Lehman, an MBA focus in finance was scary . . . that’s why everyone went into tech,” says Prof Cypher. “We’re lucky now to benefit from a strong point in the cycle . . . my hope is we get a couple more years out of it to establish our programme.”

Comments