Dark pool spotlight falls on Tradebot

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

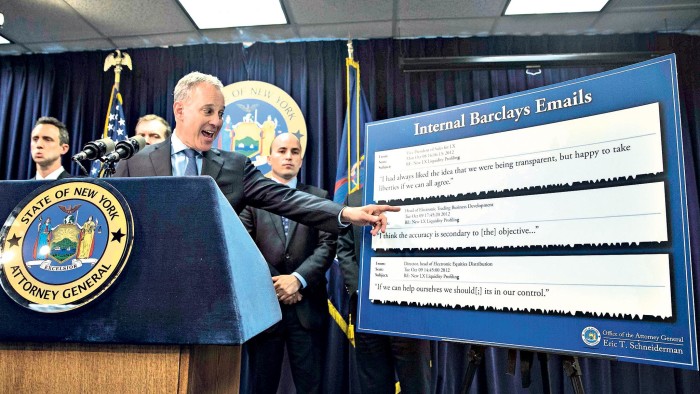

When the New York attorney-general sued Barclays this week, for allegedly misleading investors who use its anonymous “dark pool” trading venue, some of the world’s largest banks withdrew their business. But at the centre of the lawsuit was a small and little-known US algorithmic trading business, called Tradebot Systems.

From its offices in Kansas City – far from the financial hub of New York – Tradebot wears its outsider status proudly, as its mission statement underlines.

“The stock market is tough. It owes us nothing. It punishes our mistakes. Others have more money, more power, more connections. We are underdogs. We keep learning. We innovate. Every day is a new fight. Technology is our weapon. We make millions of small trades. We cut losses. We identify opportunities. We focus. The market can be beaten. We love the game.”

This combative ethos stems from Dave Cummings, a computer programmer who also worked as a commodities trader. In 1999, it occurred to him that he could build a computer system that traded faster and more reliably than a human. Fifteen years after he founded Tradebot to test that theory, his company’s belief in technology is reflected in its staffing: fewer than 100 people. Mr Cummings is no longer chief executive, but remains its owner and chairman.

And those “millions of small trades” in the Tradebot mission statement are being placed by its trading algorithms every day – with positions rarely held for more than a minute. This frenzied activity can account for up to 5 per cent of the total US equity volume on an average day, according to the company’s website.

But while Tradebot portrays itself as an underdog with few powerful connections, its computers are connected to all the main stock exchanges and big share-trading venues in the US.

That complex network now forms a key part of Mr Schneiderman’s allegation against Barclays. “Tradebot Systems had historically been, and was at that time, the largest participant in Barclays’ dark pool, with an established history of trading activity that was known to Barclays as toxic,” the lawsuit claims.

In industry parlance, “toxic” is a term that describes the effect of trading by “informed” participants who have access to better, more up-to-date information than other investors, or faster means of executing trades – two pillars of Tradebot’s strategy. By contrast, many dark pools are marketed as services for so-called “uninformed” traders with no speed advantage, such as large institutional investors.

But Tradebot’s style of computer-driven trading had been known to Barclays and others for some time.

In 2005, Mr Cummings left Tradebot to launch Better Alternative Trading Systems, a technology-dependent share trading venue backed by a group of investment banks. It has since become BATS Global Markets, now the third-largest stock exchange in the US.

In building BATS, Mr Cummings developed relationships with members of Lehman Brothers’s equity trading team, who were joined by Bill White in December 2007 when Lehman bought Van der Moolen, a market-making firm based on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange. At the time, Lehman held a 12.3 per cent stake in BATS from an early investment alongside other large global brokerages. Mr Cummings left BATS in July 2007.

Lehman’s US assets were sold to Barclays in 2008 when the US bank failed, although its BATS stake was handed over to the trustees sent in to wind down its remaining assets. Lehman’s US equity division and Mr White, however, would come to form a principal part of Barclays stock trading franchise.

By December 2010, Mr White had become head of equities electronic trading for Barclays and overseen the growth of Barclays LX, the bank’s most successful “dark pool” trading venue which steadily gained market share against its rivals.

In a press release in February 2013, Barclays boasted of its success in growing the business: “LX has seen the strongest growth among competitors, moving up nine places in the dark pool volume rankings over the past four years . . . The dark pool has attracted significant volume over the past year following enhancements to the firm’s technology, algorithmic trading and routing strategies.”

It quoted Mr White who said: “We laid out a plan two years ago to overhaul our offering end to end, gain market share and provide clients with the best electronic trading tools in the market. The number two ranking is a reflection of the success of that plan and the strength of our entire Equities franchise.”

Both Mr White and Mr Cummings, whose trading firm is not accused of any wrongdoing, declined to comment for this article.

According to a person familiar with the situation, Mr White is now focused on the investigation having been removed from his day-to-day activities, which were heading up Barclays’ electronic equities franchise, including the dark pool. He is still a full-time employee at the bank.

But Barclays’ disclosure of its trading relationship with Tradebot is now firmly under the microscope of regulators. And once again the world gets a glimpse of the complex network and interconnections behind US equities market trading.

Comments