The Circle, by Dave Eggers

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The Circle: A Novel, by Dave Eggers, Hamish Hamilton, RRP£18.99/Knopf, RRP$27.95, 504 pages

Dave Eggers’ latest book is set in the near future – very near, like tomorrow. The technology employed by The Circle – Google, Apple and Facebook all rolled into an ostensibly benevolent amalgam – is either available now or could be in the works. Perhaps that helps to explain why the text seems so hurried: it may come from a rush to print before this work seems set in the near-yesterday.

Mae is a perky, optimistic new hire at this cutting-edge California company, which allows internet users to combine email, social networks, banking and purchasing into a single identity under the clients’ real names. This new internet fingerprint has been almost universally adopted across the web, obviating countless logins and passwords. The end of anonymity has discouraged trolls and issued in a new era of online decency. Sophisticated data collection facilitates such perfectly targeted marketing that many Circle users welcome advertisements. Convenience reigns.

Yet there’s virtually no such thing as a utopian novel, is there? In fiction, that initial U has been replaced wholesale by “dys”. For sci-fi and mainstream novelists alike, perfection is inherently suspect, and the universal happiness an ideal society seeks to impose is reliably a boppy, robotic sort interchangeable with idiocy. In the Aldous Huxley tradition, a too-well-managed social order is tantamount to a police state.

With The Circle, Eggers updates this classic paradigm for the internet era, and this time the road to perdition is paved by well-meaning, tolerant-minded Silicon Valley New Agers. After all, it’s as short a distance to tyranny from the left as from the right.

The Circle’s campus would be a parody if it weren’t so close to the facilities that Google already provides for its employees: a cafeteria full of vegan and vegetarian fare, massage therapists, on-site healthcare, gyms, sports fields and dormitories. An incessant whirlwind of in-house parties, visiting musicians, films and theatrical performances helps to ensure that “Circlers” almost never have to sample the dirt and chaos of the outside world. True to dystopian convention, such a hermetic, insistently healthy workplace immediately gives us the creeps.

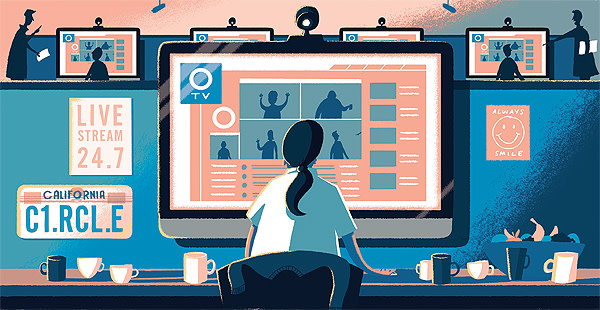

Starting out in “Customer Experience”, or Customer Services to the fusty, Mae quickly makes her mark, driven to keep her customer satisfaction rating as close as possible to 100 per cent. She “zings” (tweets) and “likes” her heart out, polka-dotting cyberspace with frowns and smiley faces. Coming to the attention of the company founders, Mae becomes the first Circler to go fully “transparent” and webcast a live, uninterrupted video stream of her whole waking life. She soon has billions of followers.

The novel’s wariness of the scale of surveillance now possible with ubiquitous cameras and vast digital storage naturally resonates with current affairs – Edward Snowden and WikiLeaks. But the book reserves its most pronounced disgust for the frantic sharing and constant craving for approval among social media participants. Convinced that every individual experience rightly belongs to all mankind, one of the Circle’s godfathers coins the Soviet-style mottos “Secrets are lies/ Sharing is caring/ Privacy is theft”.

Meanwhile, Mae’s former boyfriend complains that while “likes” and smiley faces were once the stuff of junior high school, now “it’s everyone, and it seems to me sometimes I’ve entered some inverted zone, some mirror world where the dorkiest shit in the world is completely dominant. The world has dorkified itself.” He observes, “There’s this new neediness …the tools you guys create actually manufacture unnaturally extreme social needs. No one needs the level of contact you’re purveying. It improves nothing. It’s not nourishing. It’s like snack food.” Indeed, Mae’s colleagues are so obsessed with posting pictures and chat online that non-communication “felt like violence”.

Eggers’ concerns are timely: the comprehensive invasion of privacy to which we are all becoming inured; today’s compulsive documentation of life, until it seems as if no one is actually living it; so much communication for its own sake, regardless of what we have to say; the erosion of silence, reflection and the integrity of our interior worlds by devices meant to keep us all “connected”; and the falsity of what now passes for human contact.

The problem is the writing. Even at 500 pages, The Circle reads very fast, and that’s not a compliment. However long the novel actually took to complete, it feels slapdash. There’s not a lot of terrible writing here; there just isn’t much good writing. Moreover, the prose is fat. The text is prone to provide not a single piquant detail but five merely OK details. Flabby dialogue is common: “Is this still a good time to explain Conversion Rate and Retail Raw?”/ “Sure.”/ “Has Annie told you about this stuff already?”/ “No, she hasn’t.”/ “She didn’t tell you about Conversion Rate?”/ “No.”/ “Or Retail Raw?”/ “No.”/ “Oh. Okay. Good. So we’ll do it now?”

Eggers is usually better than this. The Circle explores a number of inventive ideas, and the premise is promising. Yet because the execution is pretty lame, this novel never rises above type.

Lionel Shriver is author of ‘Big Brother’ (HarperCollins)

Comments