Takings confirm enduring appeal of cinema

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In the rapidly evolving world of personal technology, critically acclaimed episodic television and streaming media subscription services such as Netflix, Hulu and Amazon, the 100-year-old business of film seems almost quaint.

Projectors have improved and are now digital, screens have become larger and prices have soared. Yet the act of going to the cinema to watch a new movie in the company of other paying guests has barely changed in a century. With a multitude of other forms of entertainment competing for consumer time and attention, has the “silver screen” lost its shine?

The short answer is no. Yes, film is changing and adapting but the industry continues to grow, fuelled by emerging markets and “franchise” movies that spin-off sequels and interconnected films set in common cinematic “universes”, such as the superhero films released by Walt Disney’s Marvel studio.

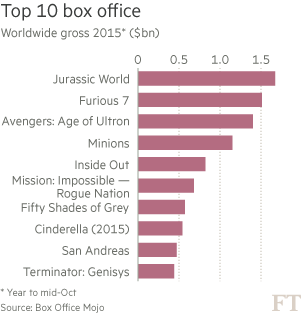

The industry is on course to score its strongest box office on record, lifted by a banner year from Universal Studios which released hits such asJurassic World and Furious 7. With the new James Bond film, Spectre, to come and the long-awaited seventh episode in the Star Wars series, north American box-office takings could exceed $11bn this year and the global total may hit $40bn in according to Paul Dergarabedian, a senior analyst with Rentrak, which measures box-office performance. The box-office forecasts compare to $10.36bn achieved in the US and $36.4bn globally last year. “This could be a record year,” Mr Dergarabedian says.

In the US, the world’s largest cinema-going market, the number of people going to the movies has been relatively flat in recent years and ticket price inflation has propped up revenues. But with a new generation raised on Facebook and Snapchat still interested in cinema, the industry can take comfort in its performance, says Mr Dergarabedian. “Given the other entertainment options this is a win for the movie industry.”

China has become the fastest source of growth. With new multiplexes springing up in urban centres and screens being added at a tremendous rate the country is on course to eclipse the US box office as the world’s largest cinema market by 2017, according to Rich Gelfond, the chief executive of Imax, the big-screen cinema group. “How Chinese and US studios react to that to grab market share is going to be very interesting,” he says.

One option for Hollywood would be to change its film release dates. The north American release calendar is wedded to US holidays, with the biggest movies released in the summer for maximum impact. “There is a large number of films concentrated around only a few dates,” says Mr Gelfond. “That approach may need to be rethought. The rise of China should play into it because it has a different calendar . . . should Hollywood change release patterns to reflect the international market?” The industry needs to take more of a global view, he adds.

China’s economy stuttered this summer but this has, to date, not worried Hollywood. “The consumer discretionary sector is holding up very well and the movie business is holding up well,” says Mr Gelfond. “Since the market started to suffer in July our box-office has held up and the number of new deals we have signed has increased.”

Imax China, the company’s Chinese subsidiary, recently raised $285m in a Hong Kong IPO, giving it a listing which will allow it to tap investors for cash to use for expansion in the region.

Studios have also been active in China. DreamWorks Animation, the studio behind the Shrek and Kung Fu Panda films formed a joint venture with Chinese partners in 2012 to create original Chinese content for the market. Other studios have sought deals with local producers to ensure their films qualify as Chinese co-productions, a status that entitles them to a far larger share of the box-office spoils.

The film industry is changing in other ways, beyond the distribution of US-made movies to fast-growing markets such as China. The rise of streaming services and the collapse of DVD sales as the industry’s biggest cash generator has forced a rethink in the industry’s business model. The traditional structure of carefully set “release windows”, whereby films are released first in cinemas then, after a period of several weeks, on DVD and released to pay-TV, is under pressure.

Theatrical distributors have zealously guarded these windows, arguing that tinkering with the model would undermine cinema-going — which often propels a film’s financial performance through its life on DVD, cable and, eventually, television. “Films will continue to come out under a windowing system for a significant amount of time,” says Mr Gelfond.

Cinemas have been the beneficiaries of another trend which shows no sign of abating: franchise movies. Loosely defined as films which can spin-off sequels, they are the holy grail for Hollywood because they have built-in awareness with audiences. When they work, they can be a licence to print money.

Seven of the 10 top-grossing movies globally in 2014 were sequels. Compare this with the year-end box office tally 20 years ago, when only one of the top 10 — Clear and Present Danger, starring Harrison Ford — was a sequel.

Disney’s Marvel unit has set a new bar for franchise movies, creating an interconnected “universe” of films populated by many of the same characters. Warner Brothers, part of Time Warner, is trying to get its own “universe” off the ground, based on characters from DC Entertainment, which it owns. Next year it will release Batman vs Superman: Dawn of Justice, a movie which throws together two of its best known characters. Legendary Entertainment, a co-producer of the Dark Knight Batman films, is also getting in on the act, striking a deal with Warner Bros to unite the “monster” franchises of King Kong and Godzilla, greenlighting a movie set for 2020, Godzilla vs Kong.

If these crossover projects sound like Hollywood has run out of ideas, well, maybe it has. But as Marvel has shown, proven characters sell movie tickets and in the costly world of film production studios will do anything they can to mitigate risk.

The success of franchise movies and studio “tent-pole” releases — so called because they can make so much money they can support an entire year of production — has clear implications for smaller, mid-budget releases.

But investors continue to show strong interest in putting their money to work in Hollywood. “There’s more capital available than there are great stories,” says Nick Meyer, chief executive of Sierra/Affinity, an international film sales and production company.

Storytelling is as central to the success of the film industry as it has always been, he says. “Stories drive intellectual property generation, they drive financing opportunities and they attract the great artists — the directors and casts.”

Many writers and directors have fled cinema for the “Golden Age” of television, epitomised by critical hits such as Breaking Bad, Mad Men and Game of Thrones.

But film continues to attract investment, says Mr Meyer. “It is an asset class that is attractive and not just to institutional investors but to personal investors. The driver is always: how do you create a good story?”

The business of film has evolved greatly but its fundamental principles remain the same. When the stars align and story, cast and director work, the result can be a financial hit on a global scale.

“The theatrical industry has taken on all-comers for the last 50 years,” says Mr Dergarabedian of Rentrak. “It is part of the entertainment diet and it’s not going anywhere.”

Comments