China’s IPO froth bubbles over

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

What’s frothier than the Chinese stock market? Chinese IPOs. They’ve become so bubbly that one concerned management team has solemnly urged the investing public to “invest rationally and pay attention to risks”.

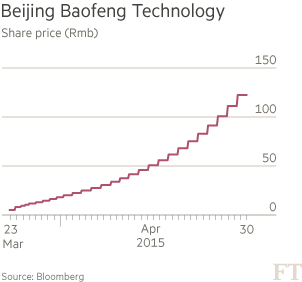

Beijing Baofeng Technology, the online video company with the worried boardroom, is the leading example of IPO excess. After jumping by the maximum-allowed 44 per cent from the offer price when it floated in Shenzhen just over a month ago, the stock has risen by the daily maximum of 10 per cent every day since.

Forget valuations; the company (“Storm” in English) has risen 17-fold in 26 trading days, making it far and away China’s best-performing stock this year. From being one of China’s tinier stocks, it is now valued at $2bn.

Others are following suit. Every one of the 29 IPOs in Shanghai and Shenzhen this month have risen by the daily limit each day since. The worst performing IPO from earlier in the year has doubled in price.

Frothy floats are one symptom of bubbles. When the stock market is wildly overpriced, stock promoters race to satisfy demand for shares through new listings. The result of indiscriminate demand is that any old nonsense can raise cash, as became obvious in the dotcom era.

There is arguably something similar going on among venture capitalists rushing to finance Silicon Valley. They are in turn attracting chancers to quit jobs elsewhere and rebrand themselves as app developers.

If the pace of IPOs in China continues, the country will be on track to come close to the record year of 2010, when there were more than 300 new listings — and the equity market started a steep two-year decline.

Still, the amount of money being raised remains small, even if there are a lot of floats. China is used to underpricing, too, thanks to rules which used to limit valuation multiples for new listings, as Jay Ritter at the University of Florida points out.

Those rules are gone. Big price pops may be spread out, thanks to the limits on daily prices rises, but soaring shares post-IPO suggest either that bankers are stage-managing floats to ensure stunning debuts, or the market is even bubblier than the stock promoters anticipated.

Comments