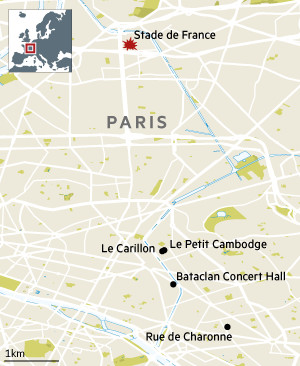

Paris witness: Simon Kuper in the Stade de France

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

I was sitting in the stadium watching the France-Germany football match when I heard the first explosion. It was very loud, and seemed to come from just outside the stadium. Most people ignored it, or even cheered: football crowds are used to firecrackers. Even after the second explosion, a few minutes later, the crowd remained in good humour and the game continued.

France-Germany is the sort of top-class entertainment that people live in Paris for: the world champions visiting the country that in seven months’ time is due to host the European Championships. Hours after the game, we found out that two suicide attacks had killed five people and injured many more just outside the stadium, a few hundred metres from our seats. More than 100 died in the city centre in separate attacks.

It was an evening of uncertainty, of trying to find out what on earth was happening. After the explosions, the crowd, bizarrely, continued to follow the match and cheer the French goals. I had stopped watching. I was on my laptop, following the rolling, horrible news, and asking myself: should I be raising my children here?

Paris attacks: Scores dead in co-ordinated assaults

State of emergency declared, military deployed and borders closed after one of deadliest operations since September 11

Read more

I have lived in Paris for 13 years. I had always thought the city worked very well. It’s been one of the great cities for centuries. There are homegrown terrorists, but most Parisians mix pretty well across ethnic boundaries.

Chiefly through my children’s school and football club, we have more or less unintentionally developed friendly contacts with people whose backgrounds range from Arab to Christian to pagan to Jew. Only the other evening, a Senegalese Muslim couple we know — our kids have played together since crèche — was sitting at our kitchen table wondering why everyone can’t just get along.

Greater Paris has 12m often rather irritable people crammed into too small a space but until now it has flourished. In fact, Paris is a miracle.

We got through the Charlie Hebdo attacks together. Most Parisians aren’t engaged in a great global struggle between religions. Like most people everywhere, they are just trying to live their lives, pay off their mortgages, and in the evening slump in front of the TV, have dinner with friends or go to a football match.

We all went on with life after Charlie Hebdo. My children’s school is next to a fairly obvious terrorist target, and they got used to walking there in the mornings watched by soldiers armed with machine-guns. After a while they barely noticed any more.

But tonight, for the first time, I am asking myself whether we can stay in Paris. Bataclan, the popular café-cum-music hall where dozens of people seem to have been gunned down tonight, is a few hundred metres from our house. (It’s also around the corner from the old Charlie Hebdo headquarters attacked by gunmen in January.)

I have eaten in the Bataclan once or twice, walked past it countless times. Now it will forever be remembered as a site of death.

A friend just rang. He was having dinner down the street from the Bataclan. A policeman told him which way to run away. On the phone he sounded hysterical. I hope he will get over this.

My wife had gone to dinner with friends. When the shootings began, my children were at home with the babysitter. I phoned the babysitter and asked her, somewhat pointlessly, to lock the door. Soon I will try to take an Uber home from the stadium into central Paris, which now seems to be a war zone with shooting in all sorts of places at walking distance from our flat.

Tonight my family will probably be OK. But after that? The whole point of Paris is to use the city. Everyone here lives in a cramped apartment. There are almost no back gardens where you can barbecue or play catch with the kids and shut yourself off from the world.

You live in Paris to go out, to meet friends in cafés like the Bataclan, to have conversations with intelligent people from everywhere, to go to football matches or to the Louvre, near which there was a shooting tonight too. Paris is all about its public spaces — the cafés, the cultural venues and the squares. No city has better ones. And when those public spaces become dangerous — and the Parisian authorities have told people not to leave home unless “absolutely necessary” — the city crumbles.

I don’t think this is a clash of civilisations. I see it as a clash of a couple of thousand jihadis with a great city. The problem — as we saw in former Yugoslavia, or in Lebanon — is that it only takes a few men with guns to make a place unlivable.

All this may be hysterical. I am writing this on an emotional night. Perhaps in a week or two things will get back to normal, as they did after Charlie Hebdo, and as they did in New York a few months after the attacks of September 11. If so, I might stay in Paris for another 13 years. But I am pessimistic. I fear that fear and danger might become the new normal here.

I do not know how to tell my children this. They love Paris. They consider themselves Parisians. They have never lived anywhere else, and have repeatedly told us we are not allowed to move. But I cannot pretend to them that everything is fine. Tomorrow, I suspect, their football match will be cancelled. Normally we would go to the local park to play. Now, I’m not sure that’s a good idea.

Comments